Factory Girl: An extract from Han Kang's Human Acts

The Gwangju Uprising was a popular rebellion in defiance of martial law in Gwangju, South Korea. To mark the anniversary of the uprising on 18 May, 1980, Verso is proud to publish an excerpt from Human Acts (Portobello, 2016) by Han Kang and translated by Deborah Smith, winners of the Man Booker International Prize 2016. Opening in the Gwangju Commune, Human Acts unfurls in the crucible of the 1980s student and worker-led democratic movement demanding an end to military rule. After a citizen’s army fought back against the crackdown on protests and ejected the military from the city, an autonomous community comparable to the Paris Commune endured for a few days until it was crushed by a military operation on 27 May that killed and injured thousands. Deborah Smith’s Introduction excerpted here contextualises the events of the uprising and is followed by a selection from the chapter ‘Factory Girl’. Featuring a women’s splinter group from the main union, the excerpt portrays the complexities around class and gender in the democratisation movement.

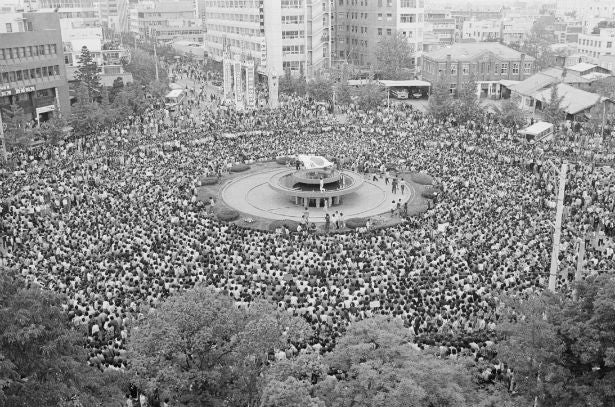

(Thousands of Gwangju citizens amassed in the city square during the May 1980 uprising)

In early 1980, South Korea was a heap of dry tinder waiting for a spark. Only a few months previously Park Chung-hee, the military strongman who’d ruled since his coup in 1961, had been assassinated by the director of his own security services. Presiding over the so-called ‘Miracle on the Han River’ – South Korea’s rapid transformation from dirt-poor and war-shattered into a fully industrialised economic powerhouse – had gained Park support from some quarters, though numerous human rights abuses meant he was never truly popular. Recently, he’d succumbed to the classic authoritarian temptation to institute increasingly repressive measures, including scrapping the old constitution and having a new one drawn up making his rule a de facto dictatorship. By 1979 things were fraying at the edges, and Park’s declaration of martial law in response to demonstrations in the far south was, to some, a sign that something had to give.

But the assassination was no victory for democracy. Instead, into Park’s place stepped his protégé Chun Doohwan, another army general with firm ideas on how a people should be governed. By May, Chun had used the excuse of rumoured North Korean infiltration to expand martial law to the entire country, closing universities, banning political activities, and further curtailing the freedom of the press. After almost two decades of Park Chung-hee, South Korean citizens recognised a dictator when they saw one. In the southern city of Gwangju, student demonstrations had their numbers swelled by those for whom the country’s ‘miraculous’ industrialisation had meant back-breaking work in hazardous conditions, and for whom recent unionisation had led to greater political awareness. Paratroopers were sent in to take over from the police, but their brutality against unarmed citizens resulted in a still greater turnout in support of the civil militias. Together, they managed a brief respite during which the army retreated from the city centre.

Shoot-outs, heroism, David and Goliath – this is the Gwangju Uprising as it has already been told in countless films, and a lesser writer might have been tempted to start with such superficially gripping tropes. Han Kang starts with bodies. Piled up, reeking, unclaimed and thus unburied, they present both a logistical and an ontological dilemma. The alternation in the original between words whose meanings shade from ‘corpse’ or ‘dead body’ to ‘dead person’ or simply ‘body’ reflects a status of uncertainty reminiscent of Antigone. In the Korean context, such issues can also be connected to animist beliefs and the idea of somatic integrity – that violence done to the body is a violation of the spirit/soul which animates it. In Gwangju, part of the magnitude of the crime was that the violence done to these bodies, and the manner in which they had been dumped or hidden away, meant they were unable to be identified and given the proper burial rites by their families.

The novel is equally unusual in delving into the complex background of the democratisation movement, though Han Kang’s style is always to do this obliquely, through the experiences of her characters, rather than presenting a dry historical account. There is the class element, much of which floats beneath the surface of the novel; because the recently unionised factory girls were some of the most vocal and visible agitators for change, the authorities were able to paint the uprising as a Communist plot sparked by North Korean spies, thus legitimising their brutal crackdown. In the chapter entitled ‘The Prisoner’, I paid special attention to diction in the hope that this would flag up the subtle politics of a working-class torture survivor being pressured into revisiting traumatic memories for the sake of a university professor’s academic thesis. And there is also gender politics, with ‘The Factory Girl’ featuring a women-only splinter group from the main union, set up to address the fact that female workers were treated more unfairly even than the men.

Another striking feature of the uprising is regionalism. It was no accident that the first rumblings, and the worst violence, were felt in the far south of the Korean peninsula, a region which has a long history of political dissent, and of under-representation in the central government. It also goes some way to explaining why the uprisings were suppressed with such brutality, and why the government was able to cover up the precise details and statistics of this suppression for so long. It wasn’t until 1997 that the massacre was officially memorialised, and casualty figures remain a con - tentious issue even today. Disputing the official figures was initially punishable by arrest and, despite being far lower than the estimates by foreign press, these have still not been revised. In terms of mentality if not geography, Gwangju was sufficiently far from Seoul to seem ‘off the mainland’ – the same kind of mental distance as that from London to Northern Ireland at the time of the Bloody Sunday massacre.

Born and raised in Gwangju, Han Kang’s personal connection to the subject matter meant that putting this novel together was always going to be an extremely fraught and painful process. She is a writer who takes things deeply to heart, and was anxious that the translation maintain the moral ambivalence of the original, and avoid sensationalising the sorrow and shame which her home town was made to bear. Her empathy comes through most strongly in ‘The Boy’s Mother’, written in a brick-thick Gwangju dialect impossible to replicate in English, Korean dialects being mainly marked by grammatical differences rather than individual words. To me, ‘faithfulness’ in translation primarily concerns the effect on the reader rather than being an issue of syntax, and so I tried to aim for a non-specific colloquialism that would carry the warmth Han intended. Though I did smuggle the tiniest bit of Yorkshire in – call it translator’s licence.

One of this translation’s working titles was ‘Uprisings’. As well as the obvious connection to the Gwangju Uprising itself, a thread of words runs through the novel – come out, come forward, emerge, surface, rise up – which suggests an uprising of another kind. The past, like the bodies of the dead, hasn’t stayed buried. Repressed trauma irrupts in the form of memory, one of the main Korean words for ‘to remember’ meaning literally ‘to rise to the surface’ – an inadvertent, often hazy recollection which is the type of memory most common in Han Kang’s book. Here, chronology is a complex weave, with constant slippages between past and present, giving the sense of the former constantly intruding on or shadowing the latter. Paragraph breaks and subheadings have been inserted into the translation in order to maintain these shifts in tense without confusing the reader.

In 2013, when Park Chung-hee’s daughter Park Geunhye was inaugurated as President, the past rose up and ripped the bandage off old wounds for Gwangju-ites like Han Kang. Her novel, then, is both a personal and political response to these recent developments, and a reminder of the human acts of which we are all capable, the brutal and the tender, the base and the sublime.

Deborah Smith, Introduction to Human Acts

***

The labour union voted against the company-dominated union by a large majority. On the day the strike-breakers and policemen came to arrest its leading members, the hundreds of factory girls who were on their way from their dormitories to the second shift of the day formed a human wall. The oldest were twenty-one or twenty-two; most were still in their teens. There were no proper chants or slogans. Don’t arrest us. You mustn’t arrest us. Strike-breakers charged towards the shouting girls, wielding square wooden clubs. There must have been around a hundred policemen, heavily armed with helmets and shields. Lightweight combat vehicles whose every window was covered with wire mesh. The thought flashed through your mind: what do they need all that for? We can’t fight, we don’t have any weapons.

‘Take off your clothes,’ Seong-hee bellowed. ‘All of us together, let’s all take off our clothes.’ It was impossible to say who was first to respond to this rallying cry, but within moments hundreds of young women were waving their blouses and skirts in the air, shouting ‘Don’t arrest us!’ Everyone held the naked bodies of virginal girls to be something precious, almost sacred, and so the factory girls believed that the men would never violate their privacy by laying hands on them now, young girls standing there in their bras and pants. But the men dragged them down to the dirt floor. Gravel scraped bare flesh, drawing blood. Hair became tangled, underwear torn. You mustn’t, you mustn’t arrest us. Between these ear-splitting cries, the sound of square cudgels slamming into unprotected bodies, of men bundling girls into riot vans.

You were eighteen at the time. Dodging a pair of grasping hands, you slipped and fell onto the gravel, grazing your knees. A plain-clothes policeman stopped in his wild dash forward just long enough to stamp on your stomach and kick you in the side. Lying with your face in the dirt, the girls’ voices seemed to swing between yells and whispers as you drifted in and out of consciousness. You had to be carried to the emergency room of the nearest hospital and treated for an intestinal rupture. You lay there in the hospital bed, listening to the reports come in. After you were discharged you could have resumed the fight, stood shoulder to shoulder with your sisters. Instead, you went back down south to your parents’ home near Gwangju. Once your body had had enough time to heal, you went back up to Incheon and got a job at another textiles factory, but you were laid off within a week. Your name had been put on the blacklist. Your two years’ experience working in a textiles factory was now worth nothing, and one of your relatives had to pull some strings to get you a job as a machinist at a Gwangju dressmaker’s. The pay was even worse than when you’d been a factory girl, but every time you thought of quitting you recalled Seong-hee’s voice: And that means . . . we are noble. You wrote to her, calling her onni, older sister. I’m getting on fine, onni. But it looks like it’ll be a while before I can learn how to be a proper machinist. It’s not so much that it’s a tricky technique to learn, just that I’m not being taught very well. All the same, I have to have patience, right?

For words like ‘technique’ and ‘patience’, you made the effort to write the hanja rather than just relying on the phonetic hangeul alphabet. You took time over the individual strokes of these characters which you’d learned at the meetings at Seong-hee’s house. The replies, when they did come, were invariably brief: Yes, that’s right. I’m sure you’ll do well in whatever job. This lasted for around a year or two, and then the letters gradually fizzled out.

It took you three years to finally become a machinist. That autumn, when you were twenty-one, a factory girl even younger than you died at a sit-in at the opposition party’s headquarters. The government’s official report stated that she had cut her own wrists with the shards from a bottle of Sprite and jumped from the third floor. You didn’t believe a word of it. Like piecing together a puzzle, you had to peer closely at the photographs that were carried in the government-controlled papers, to read between the lines of the editorials, which condemned the uprising in incensed, strident tones.

You never forgot the face of the plain-clothes policeman who had stamped on you. You never forgot that the government actively trained and supported the strike-breakers, that at the peak of this pyramid of violence stood President Park Chung-hee himself, an army general who had seized power through a military coup. You understood the meaning of emergency measure no. 9, which severely penalised not only calls to repeal the Yushin constitution but practically any criticism of the government, and of the slogan shouted by the scrum of students at the main entrance to the university. You pieced together the newspapers’ oblique strands of misinformation in order to make sense of the subsequent incidents that occurred in Busan and Masan. You were convinced that those smashed phone booths and burnt-out police boxes, the angry mobs hurling stones, formed a pattern. Blanked-out sentences that you had to fill with your imagination.

When President Park was assassinated that October, you asked yourself: now the peak has been lopped off, will the whole pyramid of violence collapse? Will it no longer be possible to arrest screaming, naked factory girls? Will it no longer be permissible to stamp on them and burst their intestines? Through the newspapers, you witnessed the seemingly inexorable rise of Chun Doo-hwan, the young general who had been the former president’s favourite. You could practically see him in your mind’s eye, riding into Seoul on a tank as in a Roman triumph, swiftly appropriating the highest position in the central government. Goosebumps rose on your arms and neck. Frightening things are going to happen.

The middle-aged tailor used to tease you: ‘You’re cosying up with that newspaper like it’s your new beau, Miss Lim. What a thing it is to be young, and be able to read such fine print without glasses.’

And you saw that bus.

It was a balmy spring day, and the owner of the dressmaker’s had taken his son, a university student, to stay with relatives in Yeongam. Finding yourself with an unexpected free day on your hands, you were strolling the streets when you spotted it, an ordinary bus on its way into the city centre. END MARTIAL LAW. GUARANTEE LABOUR RIGHTS. Yellow magic marker screamed out from the white banners which hung out of the bus’s windows. The bus was packed with dozens of girls from the textile factories out in the provincial towns, in their uniforms. Their pale faces put you in mind of mushrooms, which had never seen the sun, and they had their arms thrust out of the windows, banging sticks against the body of the bus as they sang. Their voices carried clearly all the way to where you had stopped in your tracks, and you remember them now as seeming to issue from the throat of some kind of bird.

We are fighters for justice, we are, we are

We live together and die together, we do, we do

We would rather die on our feet than live on our knees

We are fighters for justice

Every syllable so distinct in your memory. Entranced by that song, you stumbled blindly in the direction the bus had taken. A great throng of people had taken to the streets and were heading in the direction of the main square, in front of the Provincial Office. The students, who had been massing in front of their university’s main gate since early spring, were nowhere to be seen. Those filling the streets were the elderly; children of primary school age; factory workers in their uniforms; young office workers, the men wearing ties, the women in skirt suits and high heels; middle-aged men wearing sweaters emblazoned with the logo of the ‘new village’ movement, brandishing long umbrellas as though intending to use them as weapons. At the very front of this snaking column of people, the corpses of two youths who had been gunned down at the station were being pushed, in a handcart, towards the square.

Han Kang, Human Acts

Han Kang was born in Gwangju, South Korea, and moved to Seoul at the age of ten. She studied Korean literature at Yonsei University. Her writing has won the Yi Sang Literary Prize, the Today's Young Artist Award, and the Korean Literature Novel Award. The Vegetarian, her first novel to be translated into English, was published in 2015 and won the Man Booker International Prize 2016. Her second novel to be translated into English, Human Acts, in 2016, both published by Portobello. She currently teaches creative writing at the Seoul Institute of the Arts.

Deborah Smith is one of a scant handful of UK-based Korean lit translators, and definitely the only one from Doncaster. So far, her translations include two novels by Han Kang, The Vegetarian and Human Acts (both Portobello UK, Crown US), and two by Bae Suah, A Greater Music (Open Letter 2016) and Recitation (Deep Vellum 2016). In 2016 she won the Arts Foundation Award for Literary Translation and the Man Booker International Prize 2106 for her translation of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian.

Deborah founded Tilted Axis Press in 2015, a not-for-profit publisher spotlighting literature in translation. She tweets as @londonkoreanist.