Displacements of the Problem of Women's Sexualization

At the point at which we wrote these stories, we had not yet turned our attention to the way in which sexuality itself is constructed. Writing and discussing stories of this kind left us with a feeling of helplessness; how were we to identify means of defending ourselves against the forms of oppression they described? No matter how far back they went, these stories always depicted the results of an already existing repression of sexuality. Examining the notion of sexuality more closely, we found it to be represented and lived as oppression at the very moment of its emergence; thus its suppression could not be assumed, as we had hitherto believed, to consist solely in a prohibition of the sexual. But then, what is “the sexual”? In the first instance it seems clear that it is something that happens with our bodies. In an attempt then to discover the origins of our deficiencies and our discontents in the domain of the sexual, we decided at an early point in our research to focus our study on our relationships to our bodies and to their development.

Female Sexualization: A Collective Work of Memory — published by Verso in a translation by Erica Carter in 1987 — is the second volume of the Frauenformen project developed by Marxist Feminist women associated with the West German journal Das Argument. Through a structured, collective exploration of memories written down by individual members, and then discussed and rewritten by the group as a whole, the editors develop a set of theoretical reflections on the socialization of women — which here, Carter writes in her translator's introduction, "comes to appear as a process of the sexualization of the female body."

Describing the evolution of the editorial collective, Nora Räthzel writes:

We have attempted to work collectively, in other words to unite the process of teaching and learning within each individual woman. In this volume we have attempted to dismantle the kind of division of labour found in Volume One of Frauenformen, in which stories were written and rewritten by one set of individuals, for which others then elaborated a theoretical framework, more or less on their own. In what follows, by contrast, each individual has been allocated work both on and with the experiences related. The method has been a productive one, in that it has allowed each of us both to work on one special area, while at the same time participating in discussions of the more general issues raised...The whole project arose out of our fundamental unease with all the theories of socialization previously developed within psychology and sociology. On the one hand, girls are said to be accounted for by these theories — and yet they barely make an appearance. On the other hand, if and when girls do appear — as they have done in various socialization theories under the influence of the women's movement — they surface only as objects of various different agencies (the family, the school and so on), which are seen to act upon them and force them into a particular range of roles. The question of how individuals make certain modes of behaviour their own, how they learn to develop one particular set of needs as opposed to certain others, is never addressed. In no existing work did we find any indication of the existential afflictions and obstacles facing girls in their attempts to become grown-up' women.

In the excerpt below — which contains descriptions of sexual violence — collective members Frigga Haug, Kornelia Hauser, Erika Niehoff, and Nora Räthzel discuss how their conception of sexualization evolved over the course of the study and through the various projects that comprise it.

Big Brother

She, a girl barely seven years of age, tossing incessantly and turning from side to side, incapable of sleep. Over and over again, the horror-film she had been through played itself out before her eyes. Her first experience . . . how was she to behave from now on towards the brother who was nine years her senior? Why had he wanted to lie naked in bed with her? He hadn't seemed to notice how it had shocked her, how unpleasant and embarrassing she found it when his thing swelled and stiffened, when he used it to stroke her between the legs - she was still only a child. A little girl who still paid no more than passing attention to sexuality. Besides, her mother had always told her never to let any men touch her between the legs; mother had even disapproved of her touching herself down there. And yet she had been completely defenceless . . . But then again, why defend? After all, her brother hadn't forced her, he had asked her affectionately. Oh, if only her parents had been at home. Her brother wouldn't have dared to do it - as it was, she'd been afraid the whole time they'd be caught, and at one point grandma had come downstairs . . . what would have happened if they hadn't heard her in time? . . . And now it had happened a second time. She felt helpless! Every day the same thoughts plagued her, on the long journey to school and in the evenings before she dropped off to sleep. What on earth was she to do? She respected her brother and was pleased that he now accepted her; that he no longer grumbled at her as he had always done until now, out of irritation at her occasional outbursts of exuberance. And now of all times, when they were getting on so well, he had confronted her with the unpleasant necessity of denying an express wish of his. She couldn't allow it to happen again. What was she to do . . . she couldn't see it through on her own. . . only Mother could now help her . . . tomorrow she would pluck up all her courage to tell her mother about it . . . Mother was sure to put things right again.

This was one of the first stories we wrote on the theme of “sexuality.” The kind of story we might have expected: sexuality is seen to be directly to do with sex, it begins in the family and is at the same time persecuted within the family, the man is active, women and girls have no sexuality of their own, they are stroked, subjugated, raped. These stories speak a language with which we are thoroughly familiar; they are located at the centre of the discourse in which what we understand as sexuality is produced. At the point at which we wrote these stories, we had not yet turned our attention to the way in which sexuality itself is constructed. Writing and discussing stories of this kind left us with a feeling of helplessness; how were we to identify means of defending ourselves against the forms of oppression they described? No matter how far back they went, these stories always depicted the results of an already existing repression of sexuality. Examining the notion of sexuality more closely, we found it to be represented and lived as oppression at the very moment of its emergence; thus its suppression could not be assumed, as we had hitherto believed, to consist solely in a prohibition of the sexual. But then, what is “the sexual”? In the first instance it seems clear that it is something that happens with our bodies. In an attempt then to discover the origins of our deficiencies and our discontents in the domain of the sexual, we decided at an early point in our research to focus our study on our relationships to our bodies and to their development. How had we learned to live in our bodies? We set up what we called body projects; initially for all parts of the body (feet, legs, stomach, hips, waist, buttocks, breasts, neck, arms, hands, hair, eyes, mouth, nose and so on). There was no single area which seemed not to represent a problem for one or other of us. Of all projects, we were able to carry only a handful to their conclusion: the slavegirl project, the body, legs, and hair. Of the many possible approaches we outlined in the initial stages, we were able to put only a handful to the test. We wrote stories, analysed a small number of proverbs and sayings, studied the changing images of women in the Fine Arts, examined a number of the ways in which the insertion of women into social structures of authority and power occurs across the body.

Legs

. . . The photo shows my sister, one of my brothers, and me. He and I are sitting “like two young louts,” my mother says. My sister, quite proper, chaste, obedient, sits with her legs closed, carefully placed one beside the other. I still have a clear memory of the moment when the picture was taken — I was barely five years old — and the sense of triumphant defiance when, at the very last moment before the photo was taken, I could no longer be prevented from sitting with my legs spreadeagled, the image of this unseemly behaviour captured forever on film. Nowadays I realize that this feeling, this attitude of the body, of the legs, cannot so easily be expressed in the way I felt it then, as proof of independence, as a refusal of obedience, as resistance to the way I had been brought up to behave. Language refuses to render what I intend it to. Whatever I say about my legs — that they are spreadeagled, spread apart, not closed — has an aftertaste of something disreputable, something obscene, it is coloured with sexual overtones. If I want to avoid this I have to talk, not of legs, but of a whole person, whom I describe as loutish or boorish . . . and yet I know very well that everything began with my legs.

Not that my mother taught us idiocies such as to take care during visits to strangers to sit only on the front edge of the chair; on the contrary, we all agreed on the repressiveness of this kind of upbringing. But now that we (my sister and I) were old enough, and above all tall enough for our legs no longer to lift off the ground and dangle in mid-air whenever we sat down, now was the time to talk to us about correct posture. Legs were to be placed neatly alongside each other, one knee touching the other. Anything other than this makes a bad impression, Smacks of bad upbringing, it's slovenly, it’s not what pretty girls do. I did my best. My legs went independent. Whenever my attention wandered for a second, there I was sitting legs astraddle again. I pressed my knees together. Immediate discomfort. The points where they touched became unbearably hot. I felt a familiar nervousness — like the feelings I had when I clenched my hands grimly around the scissors to cut my nails. I got cramp in my legs. Slackening slightly ... impossible, my legs fell open. I tipped off-balance when they lay like this, in a straight line one against the other. Pressing my knees together gave me some support, and at the same time a little control. And yet — here it was again, this dreadful feeling, as if a piece of wood, a sharp-edged one, was clasped between my limbs. I take my heels off the ground, rock a little on my toes. “Stop fidgeting about,” says my mother, “Do you need to go to the toilet?” — “She always goes too late,” she confides in passing to her friend. Not that too, why does she have to tell everyone that? She shouldn't have betrayed me. The blue sky on the horizon of this scene, the chance to get up — the toilet was an excuse — and then not to come back. But the blue sky has gone. Only if I stay here, if I don't go out at all, can I disprove the allegation that I never go to the toilet on time. I shift in closer to the table. I'm rigid with tension. The tablecloth mercifully hides my legs as they begin to creep apart again. Why can't I do it? My sister can. She can do everything. No wonder my mother is so fond of her. She tells her secrets. I look across at her peevishly. There you ared She's not sitting with her legs together at all — she's crossed one over the other, the right one over the left one. It looks funny, it can't possibly be right. I call out loud-she's not sitting right either! My mother, accustomed to these outbursts of jealous tale-telling from me, glances up for just a moment, says, “That's not particularly nice either, but it's much better than the way you sit.”

Now that I have interrupted the conversation, I am no longer reprimanded for leaving the room. I go to the room that I share with my sister, and decide to practice sitting with my legs crossed. It's not as bad as sitting with them wide apart, and it's not too goody-goody. I decide it works well, and feel grown-up. Only in retrospect do I see that this was the cheapest possible form of protest, submitting to order whatever the cost, for even today I cannot perceive women who don't sit with their legs together as anything but somehow obscene — it embarrasses me, recognizing as I do in all those women an image of myself as I knot my legs one, two, three times or more in my struggle to keep my balance on the chair.

In our stories, we attempted to recover what we call “linkages.” By this we mean feelings, attitudes towards other people and towards the world, which have some connection with the body. In the story above, the legs are “linked-in” to attitudes and emotions in a number of different ways. Sitting with the legs apart is an attitude of resistance. But what happens to the relationship between ourselves and our bodies when they become the focal point of actions of a social nature, means to an end — that of producing a relationship to other human beings? Is the body not liable to become a means of securing our insertion into the prevailing order? This is certainly what happens in our story; the legs are crossed in imitation of the pose of the sister, who is in every way the mother's favourite. Thus our story teller, though she fails to fulfil the requirements of ideal posture, nonetheless manages to emulate the sister her mother adores; in this respect at least she is as good as her sister. Her resistance to the imposition of a prescribed leg position may be seen as slotting her into a position within the family hierarchy. This then raises the question of the connections between resistance and conformity to order or, more extremely, the question of the ways in which we impose order on ourselves by practising particular forms of resistance. There is a further linkage here, namely that between requirements on the writer to keep her legs together and “growing up.” In the first instance, she has to be tall enough for her feet to have stopped dangling in mid-air before she can be required to keep her legs together. At first she does so simply in response to comments from others; in the end these responses are transformed into a desire on her own part to be able to do what is required of her. The desire for that ability is then linked with competition for the mother's favour.

Ultimately, then, the story raises the question of why this particular position should have been imposed on girls in the first place. The social relations which made it necessary can be deduced retrospectively on the basis of the effect it has produced. Even today, the sister finds it obscene to stand or sit with legs apart. Clearly, then, something “sexual” is being signified through leg posture. In expending such large amounts of energy on keeping our legs together, we begin to feel there is something we must keep hidden, something which would otherwise be revealed to public view. It is through the activity of concealment that meaning is generated. Leg posture may be seen therefore to acquire sexual significance through being linked with a sexual organ to which it alludes in the act of concealing it. “Sexualization” is acquired without sexuality itself ever being mentioned. Instead orderliness is stressed in the training of leg posture; emphasis is placed on looking as a pretty girl should and avoiding looking like a “slag.” Even if a girl has no knowledge of the exact meaning of her parents' pronouncements on leg posture, she is likely to sense from their manner and tone that they are addressing a matter of profound significance. The linkages formed at this point are strong enough to resist all kinds of later insights and enlightenments. In our discussions, for example, the argument was put forward that while “sexuality” might generally be seen as a social construction, it was surely a matter of fact that legs splayed apart were provocative . . . after all they exposed “it” to general view. But what then of male leg posture? A man of our acquaintance suggested, as an explanation for women's adoption of particular leg postures, that “women's physical constitution simply makes it easier for them to sit with their legs close together rather than spread apart; it's their anatomy.” Arguments like this condemn the activities of women to a perpetual and sustained de-naming.

In our story, leg posture is also “linked” to personal hygiene. The sister waits too long before going to the toilet, says the mother, much to the embarrassment of the child. In our culture, toilet training (a theme we have been unable to pursue further in this context) is intertwined with the production of our bodies as sexual objects. The shame we feel in relation to our bodily orifices and their secretions or indeed in relation to whole areas of the body, is linked intimately with the sexual significance of those same bodily zones. The goal we set ourselves at this point in our project, therefore, was that of finding out how “sexualizations” of this kind arose; how parts of the body with no immediate relation to “sexuality” acquired a sexual meaning. It seemed to us that this could usefully be seen in terms of the sexualization of “innocent” parts of the body. Our question then was: how do “innocent” parts of the body become guilty?

In the Manner of Slavegirls

The trade in women as objects is a phenomenon with which we are perfectly familiar — from advertising, pornography, or prostitution. The ways in which patriarchy is structured attribute to women no desire of their own. Instead women occupy a hallowed space as objects of male desire. The stimulation of desire is, however, by no means simply a passive process. Posture, external appearance and movement are adjusted by women themselves in their attempts to conform to and reinforce the status quo. There is a name for this female participation in the reinforcement of women's subordinate status: we have called it slavegirl behaviour.

Within the women's movement, attempts have been made to escape from this relationship of subordination, to move beyond the simple reiteration of our complaints against sexist conduct on the part of men. Implicit in the decision to refuse the position of “sexual object” is a change in our own behaviour. The women's liberation movement has for example nurtured the development of a culture of sartorial resistance to prevailing images of women. Resistance of this kind defines itself in two ways. It is directed against both the gaze and the desires of men, and against the dictates of fashion: short hair, baggy trousers and women's symbols have come to denote feminist women.

In our group, the question of the ways in which women constitute themselves as slavegirls was discussed initially in a seminar in Hamburg. At this stage we were still contemplating the process of subjection simply in terms of women's display of their bodies, in other words in terms of what seemed to us to constitute unambiguously sexual invitations — the wearing of short skirts, or see-through blouses for example. It seemed relatively easy to place ourselves at a distance from such things; we ourselves already dress differently in any case — in jeans and jumpers for the most part. Yet we invariably encountered a whole series of resistances and contradictions; after all there is enjoyment to be had in wearing clothes that look good, in taking pleasure in our appearance. If at the same time we are making ourselves attractive to men who then express their attraction in ways that we find unpleasant, then surely this is no concern of ours; their responses are their own affair. Are we to impose restraints on ourselves, merely in response to the reactions of men? It seemed to us that making ourselves look good did not automatically place us in the slavegirl position. We had the option of developing self-confidence in our bodies, not having to conceal them at every turn; what could possibly be wrong with this?

We see these arguments now as attempts to set ourselves apart from the slavegirl image, to repudiate any suggestion that we might be beautifying or displaying ourselves for the benefit of others, to defend our actions as sources of pleasure and self-confidence. Women in the Women's Liberation Movement have suggested, rightly, that enjoyment, pleasure, women's own desires should be seen as offering the prospect of a potential future liberation. Here enjoyment and pleasure are implicitly assumed to be extra-historical quantities standing in eternal opposition to oppression. In our stories, by contrast, we have detected a connection between pleasure and subjugation; or to put it another way, we saw ourselves taking pleasure in the very process of being trained into particular dominant structures rather than feeling tyrannized by them. Our work in the following pages is based therefore on the hypothesis of an intimate association between the subordinate status of women, and female pleasure. The question we will be asking is one that relates to our potential for liberation: what social relations — by which we mean both objective structures and their subjective apppropriation — must prevail if we are to dismantle the edifice of domination, while at the same time rescuing its pleasures for ourselves?

Our aim in these stories has been to investigate the ways we move within the dominant social order, the points at which we submit to our subjection and oppression. The first stories we wrote on women's attempts to impress others by their external appearance revolved almost without exception around clothes; it was here that submission and voluntary servitude seemed to us to express themselves most clearly.

A Carefully Staged Moderation

They had arranged to meet that evening. She spent the whole day in a state of nervous excitement, and the closer it came to the appointed time, the more agitated she became, like a young girl on her first date. Tonight's meeting though, was of a different kind. True she had fallen head-over-heels in love, but she knew that the attitude of the other towards her was of extreme ambivalence and caution. She knew that the other didn't think of her as gay, only eccentric — an impression she had to dispel at all costs. After all, she had other qualities. So what on earth was she to wear? She had to look as self-effacing as possible, she mused, the other showed a demonstrative lack of concern for her external appearance. More or less everything she had to hand for this evening seemed overly brash. She decided on jeans. The rest would have to come to her after her shower. Body odour was something she wanted to avoid at all costs, although she was likely to get clammy hands at the mere approach of the other. The question of what she was to wear on top now simply had to be resolved. She decided on a man's vest, white, under a blue lambswool pullover. A further problem — shoes! She had nothing that showed the right amount of classical discretion, her boots were too pointed. Her brown suede boots would surely do, they were nice and chunky, if a little high. No doubt the other considered her too tall anyway, for the first time in a long time, this “superiority” of hers became a source of discomfiture. Never mind, the shoes would have to do, now what about the hair? Maybe she ought to have it cut after all? She could tie it back in a plait, then at least it wouldn't look tarty. But the plait just wouldn't stay in place this evening — all it did was emphasise her prominent ears. She tried to smooth her hair down against her head but was only minimally successful. As for her face, she did no more than attempt to cover her spots — the other had none and, like all women with clear skins, was bound to find spots disgusting. She was now to all intents and purposes ready, if not exactly confident. On the spur of the moment, she changed the light blue pullover for a dark blue one which looked less fussy, grabbed a grey scarf and the old trench coat (which the other would surely not object to) and set off.

The most immediately obvious feature of this story is the fact that it is not for a man that the woman mobilizes her competence as slavegirl, but for another woman. Are relationships between women thus structured in exactly the same ways as relationships between the sexes? Does the only difference consist in a reversal of the standards by which appearance is assessed? In the story the primary concern of the writer is to produce an external appearance that conveys particular meanings relating to herself as a person. She hopes in so doing to show that she also possesses other “inner qualities.” It remains unclear what those qualities are. It does, however, seem possible for her to convey them by making herself appear in a particular light. The qualities she is after clearly do not relate exclusively to the body; she does not define them for example in terms of a specific waist measurement or a sexy leg. The expressions she uses to describe the relationship between clothing and social meaning are clichés familiar from the jargon of fashion: “discreet” and “classical.” The context in which they occur is, however, an unusual one. The writer's concern is not, for example with discretion for the sake of “elegance” but with a kind of discretion designed to create the impression that she attaches no importance to external appearance. Despite the displacement of context, meanings generated within the dominant culture are in operation here; the writer's use of “discreet elegance” both demonstratively silences any reference to “money,” and at the same time signifies that she has no need to “bother” excessively about dress. But in the subcultural context, her “restraint” produces similar meanings to those “outside” it: her clothes convey a sense of her personality as founded on something “other” than external appearance, on her character. So tenacious is the connection between clothing and personality in our culture that we remain imprisoned within the dominant structures it produces, even as we set about resisting them. It is only the solidity of the connection between dazzlingly smart shoes and the importance attached by the wearer to her appearance, which makes it possible to perceive a reversal of the association as similarly unambiguous.

In an attempt to gain a clearer understanding of the effects on women of their training in “slavegirlishness,” we propose to pursue the question of the association between clothing and personality through two stories on further aspects of the body.

The Body

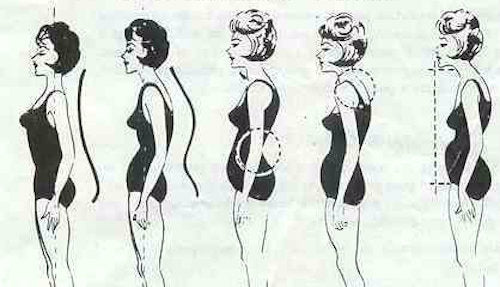

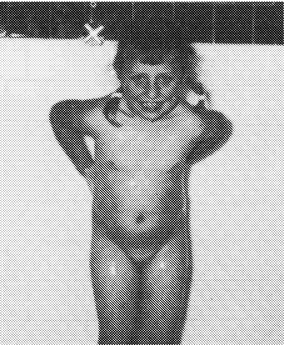

The response of most members of the group to the pictures accompanying the following story was laughter: “You mean to say this was how you used to look?” They all found the girl's appearance comical, her tummy quite clearly excessively podgy. As women we “know” how we are supposed to look; we know what remains within the bounds of acceptability and what goes too far. The term we have found for this in the group is a knowledge of the proper “standards.” While on the one hand it may be possible to increase our self-confidence by meeting these standards, it is on the other hand impossible to match up to them in reality. Erving Goffman, in his book Stigma gives the following example of this: “For example, in an important sense there is only one complete unblushing male in America: a young, married, white, urban, northern, heterosexual Protestant father of college education, fully employed, of good complexion, weight and height, and a recent record in sports.”

For Goffman, then, men are defined as acceptable according to racist and sexist standards; the question of class meanwhile is rendered more or less unrecognizable by its incorporation into standards relating to education and full employment. For reasons of time and energy, we have limited our investigation into the standards operative in our context to only one of all their different dimensions. As standard requirements for the external appearance of man, Goffman notes “good looks” and “normal weight.” For women, these are merely the points of departure for more final differentiated requirements: there is a precisely determined relation between chest, waist and hip measurement, there are such things as ideal measurements, an ideal height, an ideal weight, each with its own method of calculation. (I myself remember one particularly “precise” method. I had to multiply my chest measurement taken at mid-breast by my height, then divide the total by 240. By then dividing my actual weight by the ideal weight thus calculated, I arrived at a number against which I could gauge the extent to which I was overweight. The numbers corresponded to four categories, 1. 10 to 1.25 indicating slight plumpness, over 1.5 indicating extreme obesity.) A woman has recourse to particular methods to establish whether and in what way she is defective. There is a particular position which her breasts, for example, are supposed to occupy. The question of whether she has sagging breasts or not is not merely a question of the way she appears; it is verifiable by the pencil test. If a pencil stays put when placed under the breasts, then they sag; if not she's in luck, one more point in her favour. It is the unattainability of standards such as these that makes them so effective and which lays the foundation for women's lifelong preoccupation with their bodies. Our work in the group has been based on the assumption that our concern with standards cannot be seen simply as a superficial veneer; the clear waters of theoretical insight will not necessarily wash us clean. This is not to say that we ourselves have always avoided the pitfalls of pseudo-enlightenment. When shown the above photograph of the little fat girl, one woman in the group exclaimed, “I can't see what all the fuss is about; she looks perfectly normal to me. “Her attitude was one of “pseudo-enlightenment,” in the sense that it fostered the impression that the standards we adhere to can be neutralized through knowledge, whereas in fact they are an integral part of our personalities. Knowledge alone is an inadequate means of escape from their formative power. How then do these evaluative standards become part of our personality and with what needs and interests are they associated?

The Story

The father is an amateur photographer. He works in his darkroom, developing films. The assembled family sits looking at the photos he has taken. “You ought to watch your daughter, her tummy's too fat.” “Oh come on, she's only a child, it's puppy fat. It'll disappear of its own accord when she gets older."

What passes through the mind of the child in the course of the conversation? — Perhaps: "There he goes again, finding fault with me: does she have to be so noisy, she disturbs him on Sunday when he's trying to sleep off Saturday excesses, what's more she's a girl, something he never wanted (so her mother says), and now to cap it all her tummy's too fat — after all, she is a girl, he has said.” She doesn't care, of course. Her “strength” is in her position at school — “strength” in the literal sense. She has a friend, too, who is clearly in awe of her. Both of them used to have long plaits, she cut hers off and her friend followed suit. Her friend is pretty and dainty. She tyrannizes her.

She enjoys the fights she often gets into with boys. They've made it into a game in which points are awarded for victories and defeats. Her points total places her in the top third. One day she managed to get one boy on the floor. She held his legs high against her chest so as to be able to kick his behind. He kicked out at her chest. She felt a sudden searing pain, like nothing she'd ever felt before. She kept going, emerged the victor once again, then went on her way and — burst out crying. It was over. She was turning into a girl. No longer would she be stronger than the boys, she was turning into a weakling, becoming girlish. No different from all the stupid cry-babies, dirty fighters who scratched and bit and pulled your hairl She began to pick fights with girls who annoyed her, one who couldn't speak German, whose skirts were too long — facts to which the boys had been indifferent. At some point in this period she must also have begun to look at herself more often in the mirror and to see that she was simply overweight. Above all, it was her stomach that was too fat.

The story reads like a weather forecast. Bright at first, clouding over later. The first part transmits a sense of the normality of everyday disruptions. A series of different moods, meanings, and value judgements float through the girl's life, disparate and unconnected as clouds in a mackerel sky. Then in the second part, unexpected and unannounced, the storm breaks. A catastrophe has broken; the writer is turning into a girl.

Strange the tricks our memories play. Events are etched on our memory as the triggers of change; we see our socialization and the construction of our identity, in retrospect, marked by twists and turns, breaks and fractures. We would not wish to claim that memories of this kind are simply fallacious, a retrospective exaggeration of quite insignificant events. Yet it does seem to us problematic that this kind of remembering of crisis-points veils the normality and the petty, everyday character of our socialization — making it impossible to perceive it as a problem. In an endeavour to portray crisis as extraordinary, we make it seem as if the rest of life proceeds quietly on its way, free of crises, harmoniously — and that decisive changes occur as the result of catastrophe. Instead of this, we should perhaps begin from the premiss that all developments contain an element of crisis and thus that crisis itself has an everyday quality; that the catastrophe is prepared well in advance, and is itself the result of a general training in the normality of heteronomy.

The first part of the story presented above is written in an almost deliberately understated way — the calm before the storm. We learn little of the girl's own feelings when her father talks of finding her tummy too fat. Her observation that this represents only one of the many paternal rejections she has experienced gives only a distant inkling of her hatred of her father in the everyday life of the family. Her somewhat forced unconcern is hastily suppressed by references to her popularity at school, and to her possession of a friend. Her description of her indifference to the fatness of her stomach contrasts sharply with her body posture and facial expression in the pictures. For the group, this contrast raised the question of the kinds of diversionary manoeuvres and tactics of deflection with which women responded to bodily “stigmas.” These may range from “wardrobe engineering” (stripes to accentuate our best features), through sartorial torture (corsets) to self-deception within strategies of displacement and desensitization: my mother's liberal use of proverbs — “Beauty is more than skin deep” — for my consolation. In the next breath she was quite capable of saying, “Stand up straight, you'll never find a husband that way.” Perhaps, then, we are simply incapable of living with our anxiety over the fulfilment of bodily standards, without comforting ourselves with a notion that the true core of our personality will remain impervious to superficialities. At the same time, the use of these diversionary tactics and strategies is experienced as a destabilizing influence on the person of the woman in question; for she is aware of her own deceit, she knows that she is someone other than the person she would have others believe her to be. It is the fear of being found out that causes her insecurity. And insecurity in turn prepares the ground on which strategies of domination can take root, securing her willing submission to subjugation, to normality.

The question we set out to research in our body project was formulated in terms of our internalization of the standards that our bodies are to reproduce. In posing this question, or rather in working on memories associated with it, we hoped also to gain a better insight into the origins of our feelings in relation to our bodies, into the things we did and did not take for granted, and into the ways in which this contributed to our integration into the prevailing order of social relations. The way our bodies are to be is determined not only by behaviour directly related to the body (such as diet, sport, concealment or exposure of various parts of the body). In accepting certain “standards,” we acquiesce also in a particular relationship to others, to the identity offered us by those relationships. The history of female socialization as the centring of women around the body has yet to be written; our work here represents no more than an initial step in this direction. Massive difficulties arose in the process of our writing and remembering. After all, in a way that we are more willing to deny than to acknowledge, we ourselves, our bodies, are that of which we write. At the same time, the body is also alien to us; and it is in our sense of its strangeness that awareness begins to dawn of the heteronomous structures that enclose it, and in which the body becomes the medium through which we are inserted into the prevailing social order.

Hair

Hair has unique characteristics. We aren't stuck with our hair as we are with our bodies. Ultimately, it can be cut off, shaved, removed, dyed or otherwise transformed. In the initial stages of our project, while we certainly acknowledged the weight of symbolic significance accorded to hair as sinful, functional, seductive and so on, we considered it unlikely that writing and research on hair would be as emotionally disruptive as writing on other subjects. It would be something to be enjoyed — or so we thought initially. In the following, we have reproduced the first story written on the complex of relations around “hair.”

On fluff and what it can become

The lights were red. She waited at the crossroads on her bike. Beside her another bike rider waited for the lights to turn green. He seemed to be inspecting her profile. In retrospect, it seems almost unimaginable that a passing remark from him — “Did you know you had a beard?” — if indeed this was the expression he used — could have been the cause of a problem which was repeatedly to take possession of her, pressing for change. Could she now reconstruct the individual steps of its development? She was 16, and longing for a boyfriend, when the fluff on her chin first became a problem. She bought a tube of Pilca, then other hair removing creams; they left occasional burn marks on her chin. Wax was another remedy she tried.

At the age of 18 — a man was showing interest in her — she paid a visit to a dermatologist, and asked, curling up inside from shame, if she could remove the small prickly hairs which had now appeared. The doctor, a woman, was surprisingly sympathetic, and seemed immediately prepared to help her. The first appointment was made, it ended in fiasco. The doctor, having examined her chin more closely, refused her treatment. “That's quite a growth you've got there!"

At some stage, she had taken to using tweezers to pluck them out, from now on, she was careful not to go anywhere without them. It seemed that her boyfriend of the time was unworried by the hairs which she removed so carefully, not only from her chin, but also from her breasts and stomach.

The first letter written to her by her new boyfriend opened with the words, “My sweet Baby Bear.” She was at once thoroughly alarmed that he had detected “it,” and at the same time relieved to be able to tell him the “whole truth” this early on. He himself was so good-looking and intelligent, would he still want her now he knew of this stain on her person? She wrote to him; his reaction was cautious. She made an appointment at the hospital for hormone tests. She had also heard that the rate of growth would be slower if she had a baby. The results of the tests were within the spectrum of the “normal.” Their parting remark, after all this trouble: “What on earth do you expect — it's no more than five minutes a day. You should see some of the cases we deal with in here.”

The new Pill they were trying out at the clinic contained only a minimal proportion of male hormones. This was the period when she put on so much weight, she ate like a pig. After six or nine months, her anxieties had abated. She came off the Pill. Later, her boyfriend's reaction to her beard became more or less good-humoured.

Her youngest sister was being treated in hospital for acne. During the treatment, her cosmetic surgeon noticed the excessive hair growth on her chin, which she said was always likely to cause inflammation, she suggested the hair should be removed by electrolysis. Now, one year later, the process is complete. The scars are scarcely visible.

If only she had had her sister's luck at the same age. At the moment she is considering embarking on the treatment herself. She has no boyfriend at present.

The writer cried when she read us this story. She is now over thirty, successful in her work, well liked. We were stunned. At first, in our initial encounters with the subject of hair, we had forgotten that it is not only visible in decorative ways; that hair is not only something femininity “permits” women to wear. We were certainly conscious of the linkage made between hair and gender — after all, we were all familiar with the hatred of respectable burghers for long-haired male protesters or for the cropped hair of their young female counterparts. Our historical deliberations on the subject of hair led us initially to focus on the social embedding of changing fashions in hair, as well as on the relationship between hair length and status or gender positioning. But we had given no thought to the depth of feeling likely to be evoked by the relationship between hair and gender identity; we had not seen it, as this one writer did, as structuring her activities, her relationships, her consciousness of self. Nonetheless, even on a first reading of this story, we saw our own selves reflected in many of its finer details. Tweezers and depilatory creams, visits to the doctor, reactions to the Pill, subterfuge and disclosure; all of these were practices known to us from our own day-to-day lives. Even if we ourselves no longer practised these activities, they remained operative as repressed doubts in relation to our earlier selves.

And once again we were left with the impression that the extraordinary condensation taking place in the story, the writer's obvious unhappiness, must surely have arisen out of some barely-perceived, ordered daily training in normality. We decided then, to appoint to the group working on the “hair” project the express task of drawing up a social biography relating specifically to proper hairstyles and “decency.” Our aide-mémoire for this purpose was a photo album. The memories it brought to the surface on the theme of “one girl and her hair” were so extensive that we were again forced at an early stage to summarize and shorten our conclusions. Apparently there is no single phenomenon that cannot be made to act as an ordering force in the process of socialization. Or, at least this holds for the female body and its constitution.