"I got back to the prison with staples in because of the c-section." An excerpt from Inside This Place, Not Of It

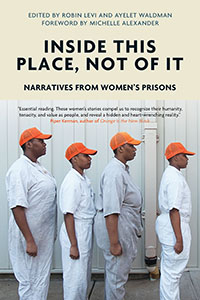

An excerpt from Inside This Place, Not of It, edited by Robin Levi and Ayelet Waldman.

Inside This Place, Not Of It documents the experiences of inmates of women's prisons in their own voices, revealing human rights violations and illustrating their harrowing struggles for survival. In this excerpt, Olivia Hamilton describes her experience giving birth in a Pennsylvania prison.

I was taken to prison with other inmates in a cramped, hot van. Some of them were also pregnant. When we got there and were getting off the van, the guards started yelling at us, “Nobody cares if you’re pregnant! You shouldn’t have got in trouble. You’re a sad excuse for a mother. You don’t care about your kids!” It was a mess. It was real hard. There was another girl there who was pregnant, and she’d been there before. She said to me, “Don’t let them get to you, girl.” But they had already gotten to me. I just felt like this wasn’t the place I was supposed to be.

The guards wanted me to stand up straight, but I couldn’t. I was totally drained because I hadn’t slept since three that morning. I was eight months along at this point, and I was huge. Eventually, one of the male guards said, “Okay, go get her a wheelchair.” The female guards were actually harder on me. So I got in a wheelchair, and they rolled me on inside. When I got inside, the guards made me strip, bend over, all that. Then they made me take a shower, and afterward they gave me a sandwich and a juice. You would think that they’d give you more food, being pregnant, but they don’t. You just eat what everybody else eats.

It was a whole process. I had to learn how to talk to the guards, and that I had to address them with “Ma’am” or “Sir” and “Good morning.” Or when they walked by, I had to stop. I had to ask permission to speak. Finally they gave me all my stuff in a bag to put on the bed.

I couldn’t carry the bag like they wanted me to. There’s a certain way you had to hold it, a certain way to walk, and I just kept dropping it. It was about ten pounds—it’s your clothes, it’s everything in there—and I wasn’t even supposed to be lifting that. But the guards kept yelling, “You’d better not drop it again!” And I was like, “Uh, ma’am, this is heavy. I’m trying my best.”

When I got in the dorm, the inmates were pretty cool and they helped me make my bed. I think, with most of the women in there being mothers, they could imagine how it felt to go through this while pregnant. Most of them were pretty understanding, and they didn’t mind helping me out as much as they could.

My due date was May 24, 2008, just before Memorial Day weekend. A female doctor from the Atlanta Medical Center came to visit me on the 22nd. At that time, I wasn’t showing any signs of labor. We did an ultrasound, and the baby hadn’t moved one bit. I wasn’t dilated at all, wasn’t even close, and I wasn’t having any pains. She said I should be ne through the weekend, and that everything was normal about my pregnancy.

Then, on the evening of the 23rd—this was a Friday evening—the guards called me, and they told me to pack my stuff. But I hadn’t even had one contraction, so I asked a guard, “Where am I going?” And the guard said, “I don’t know. They just called and said for you to pack your stuff.” I thought, Okay, maybe I’m going home!

I got over to the infirmary, and the captain said, “Well, the doctor from the prison says he’s going to send you in to be induced.” When I asked why, she said, “Because your due date is May 24th, and this is a holiday weekend.” I said, “But I’m not even in pain or anything! I don’t want to be induced, I’m not even late. Nothing’s wrong with me!” And she said, “Well, these are orders.”

They put me in a room and shackled me. I was more upset than anything that the baby just wasn’t ready, and I didn’t want to be forced. They gave me Pitocin, but it wasn’t working. Later, in the middle of the night, the doctor came in to check on me. He came in and he started poking inside me with an instrument—I’m not sure exactly what it was, it looked like a little stick. He put it inside me and started poking the bag of water, where the amniotic fluid was, so he could bust it. It was a lot of pain, and I said, “You’re hurting me.” He stopped, but by then he had swollen up my insides, and the baby wouldn’t move any more than six centimeters.

Then he said, “Well, if you don’t move any more by tomorrow, we’re going to have to do a c-section.” I said, “So you come in here, and you poke me to death, and now I’m swollen! I have never had a c-section in my life. My oldest son was nine pounds—no cuts, no slits, no nothing. And you’re going to make me have a c-section?”

The next day, the doctor came back and took me in to have the c-section done. A sergeant came in and said, “She needs to be shackled. She’s no different from anybody else.” I was hurting, and I was tired. I said to the sergeant, “Ma’am, there is no way I need these shackles. I’m not going anywhere; I’m in pain. You’ve got a guard in my room. And I don’t know if you have kids, but this ain’t something fun to have your hands shackled for.” But she made them keep the shackles on me when I went in for the c-section.

The doctor gave me an epidural. I went through with the c-section, and finally, the baby came on out. It was a boy. The guard held him up to show him to me. Even then, they never took the shackles off me.

This c-section I was forced to have—I doubt that it’s legal. I don’t remember signing any paperwork, but I never looked into finding a lawyer. I was hoping there was something I could do, but I was told that I had no rights. The guard said to me, “You lost your rights the day you walked in here.”

I named the baby Joshua. I wonder about him; does he remember all that we went through? The guards made me put the prison address on the birth certificate. That’s something you have to deal with for the rest of your life.

I was fortunate, you know. One of the guards there gave me her cell phone because she didn’t agree with a lot of what was going on. She said, “Call your boyfriend. Let him know you had the baby.” She let me talk to him until the phone died. It was a blessing.

After I left the hospital, my boyfriend picked up the baby and took him home. I guess for me, walking out of that hospital, knowing I was leaving my son—it killed me inside. I felt like I was being punished for the one mistake that I’d made in my life. I just remember looking at my baby, and kissing him, and crying, and not wanting to go. The nurse who was holding him was really hurt too. She asked me, “Do you want to kiss him again?” And I kissed him one last time, and they took me out the door.

It felt like my baby was dying, that I was abandoning him. I felt like I owed it to him to be there, and I wasn’t. I felt like maybe he would hate me, or resent me, or when I got home, he wouldn’t know who I was. It hurt. It just hurt.

I got back to the prison with staples in because of the c-section. But I couldn’t go back to the dorm until the staples came out, and so, on top of me being hurt and stressed, they put me in this infirmary with nothing but four walls. I didn’t have any of my personal property, and there was no TV, nothing.

I was supposed to stay there through the weekend. During that time, I had nobody to talk to, and all I could really do was cry. I didn’t want to eat, I didn’t want to do anything. And then one of the guards told me, “Well, if you don’t eat, we’re going to make you stay here longer.” So I made myself eat because I didn’t want to stay in there that long. All that was going to do was drive me more crazy than I already was…

The day I got out of lockdown was the day I got the news that I was going home on August 14. I had two weeks left! I thought, Thank God! Finally! I stayed up the whole night before the 14th—I was so excited, and I just wanted to leave. I was just so ready to get out of there.

An excerpt from Inside This Place, Not of It, edited by Robin Levi and Ayelet Waldman.