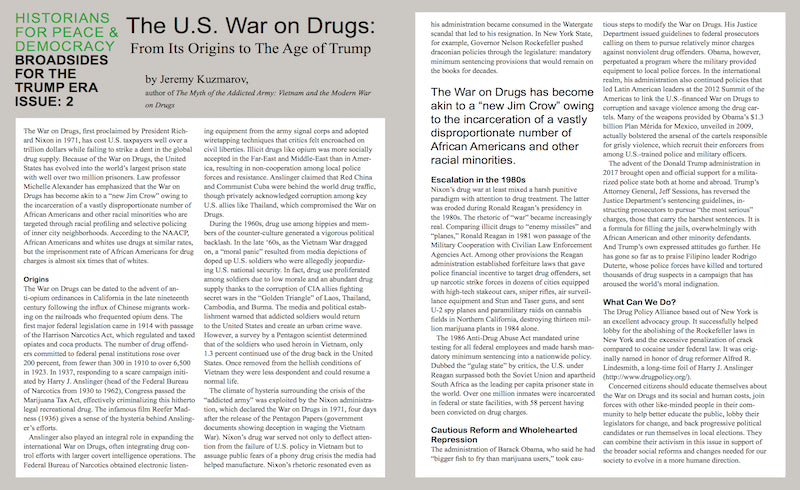

Broadside for the Trump Era: The U.S. War on Drugs — From Its Origins to The Age of Trump

A compact, printable summary of the US War on Drugs by historian Jeremy Kuzmarov.

Broadsides for the Trump Era is a series of one-page, printable handouts commissioned by Historians for Peace and Democracy. Each broadside presents a brief summary and analysis of a moment in American history that informs one element or another of the Trump presidency.

Click here to download Broadside #2: The U.S. War on Drugs: From Its Origins to The Age of Trump by Jeremy Kuzmarov, author of The Myth of the Addicted Army: Vietnam and the Modern War on Drugs.

The War on Drugs, first proclaimed by President Richard Nixon in 1971, has cost U.S. taxpayers well over a trillion dollars while failing to strike a dent in the global drug supply. Because of the War on Drugs, the United States has evolved into the world’s largest prison state with well over two million prisoners. Law professor Michelle Alexander has emphasized that the War on Drugs has become akin to a “new Jim Crow” owing to the incarceration of a vastly disproportionate number of African Americans and other racial minorities who are targeted through racial profiling and selective policing of inner city neighborhoods. According to the NAACP, African Americans and whites use drugs at similar rates, but the imprisonment rate of African Americans for drug charges is almost six times that of whites.

Origins

The War on Drugs can be dated to the advent of anti-opium ordinances in California in the late nineteenth century following the influx of Chinese migrants working on the railroads who frequented opium dens. The first major federal legislation came in 1914 with passage of the Harrison Narcotics Act, which regulated and taxed opiates and coca products. The number of drug offenders committed to federal penal institutions rose over 200 percent, from fewer than 300 in 1910 to over 6,500 in 1923. In 1937, responding to a scare campaign initiated by Harry J. Anslinger (head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics from 1930 to 1962), Congress passed the Marijuana Tax Act, effectively criminalizing this hitherto legal recreational drug. The infamous film Reefer Madness (1936) gives a sense of the hysteria behind Anslinger’s efforts.

Anslinger also played an integral role in expanding the international War on Drugs, often integrating drug control efforts with larger covert intelligence operations. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics obtained electronic listening equipment from the army signal corps and adopted wiretapping techniques that critics felt encroached on civil liberties. Illicit drugs like opium were more socially accepted in the Far East and Middle East than in America, resulting in non-cooperation among local police forces and resistance. Anslinger claimed that Red China and Communist Cuba were behind the world drug traffic, though privately acknowledged corruption among key U.S. allies like Thailand, which compromised the War on Drugs.

During the 1960s, drug use among hippies and members of the counter-culture generated a vigorous political backlash. In the late ‘60s, as the Vietnam War dragged on, a “moral panic” resulted from media depictions of doped up U.S. soldiers who were allegedly jeopardizing U.S. national security. In fact, drug use proliferated among soldiers due to low morale and an abundant drug supply thanks to the corruption of CIA allies fighting secret wars in the “Golden Triangle” of Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Burma. The media and political establishment warned that addicted soldiers would return to the United States and create an urban crime wave. However, a survey by a Pentagon scientist determined that of the soldiers who used heroin in Vietnam, only 1.3 percent continued use of the drug back in the United States. Once removed from the hellish conditions of Vietnam they were less despondent and could resume a normal life.

The climate of hysteria surrounding the crisis of the “addicted army” was exploited by the Nixon administration, which declared the War on Drugs in 1971, four days after the release of the Pentagon Papers (government documents showing deception in waging the Vietnam War). Nixon’s drug war served not only to deflect attention from the failure of U.S. policy in Vietnam but to assuage public fears of a phony drug crisis the media had helped manufacture. Nixon’s rhetoric resonated even as his administration became consumed in the Watergate scandal that led to his resignation. In New York State, for example, Governor Nelson Rockefeller pushed draconian policies through the legislature: mandatory minimum sentencing provisions that would remain on the books for decades.

Escalation in the 1980s

Nixon’s drug war at least mixed a harsh punitive paradigm with attention to drug treatment. The latter was eroded during Ronald Reagan’s presidency in the 1980s. The rhetoric of “war” became increasingly real. Comparing illicit drugs to “enemy missiles” and “planes,” Ronald Reagan in 1981 won passage of the Military Cooperation with Civilian Law Enforcement Agencies Act. Among other provisions the Reagan administration established forfeiture laws that gave police financial incentive to target drug offenders, set up narcotic strike forces in dozens of cities equipped with high-tech stakeout cars, sniper rifles, air surveillance equipment and Stun and Taser guns, and sent U-2 spy planes and paramilitary raids on cannabis fields in Northern California, destroying thirteen million marijuana plants in 1984 alone.

The 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act mandated urine testing for all federal employees and made harsh mandatory minimum sentencing into a nationwide policy. Dubbed the “gulag state” by critics, the U.S. under Reagan surpassed both the Soviet Union and apartheid South Africa as the leading per capita prisoner state in the world. Over one million inmates were incarcerated in federal or state facilities, with 58 percent having been convicted on drug charges.

Cautious Reform and Wholehearted Repression

The administration of Barack Obama, who said he had “bigger fish to fry than marijuana users,” took cautious steps to modify the War on Drugs. His Justice Department issued guidelines to federal prosecutors calling on them to pursue relatively minor charges against nonviolent drug offenders. Obama, however, perpetuated a program where the military provided equipment to local police forces. In the international realm, his administration also continued policies that led Latin American leaders at the 2012 Summit of the Americas to link the U.S.-financed War on Drugs to corruption and savage violence among the drug cartels. Many of the weapons provided by Obama’s $1.3 billion Plan Mérida for Mexico, unveiled in 2009, actually bolstered the arsenal of the cartels responsible for grisly violence, which recruit their enforcers from among U.S.-trained police and military officers.

The advent of the Donald Trump administration in 2017 brought open and official support for a militarized police state both at home and abroad. Trump’s Attorney General, Jeff Sessions, has reversed the Justice Department’s sentencing guidelines, instructing prosecutors to pursue “the most serious” charges, those that carry the harshest sentences. It is a formula for filling the jails, overwhelmingly with African American and other minority defendants. And Trump’s own expressed attitudes go further. He has gone so far as to praise Filipino leader Rodrigo Duterte, whose police forces have killed and tortured thousands of drug suspects in a campaign that has aroused the world’s moral indignation.

What Can We Do?

The Drug Policy Alliance based out of New York is an excellent advocacy group. It successfully helped lobby for the abolishing of the Rockefeller laws in New York and the excessive penalization of crack compared to cocaine under federal law. It was originally named in honor of drug reformer Alfred R. Lindesmith, a long-time foil of Harry J. Anslinger (http://www.drugpolicy.org/).

Concerned citizens should educate themselves about the War on Drugs and its social and human costs, join forces with other like-minded people in their community to help better educate the public, lobby their legislators for change, and back progressive political candidates or run themselves in local elections. They can combine their activism in this issue in support of the broader social reforms and changes needed for our society to evolve in a more humane direction.

Suggested Reading

Sasha Abramsky, American Furies: Crime, Punishment and Vengeance in the Age of Mass Imprisonment (Boston: Beacon Press, 2008).

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Color-Blindness (New York: The New Press, 2010).

Radley Balko, The Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces (New York: Public Affairs, 2014).

Howard S. Becker, Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance, rev ed. (New York: the Free Press, 1997).

Alexandra Chasin, Assassin of Youth: A Kaleidoscopic History of Harry J. Anslinger’s War on Drugs (University of Chicago Press, 2016).

David T. Cortwright, Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001).

Johann Hari, Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015).

Carl Hart, High Price: A Neuroscientist’s Journey of Self-Discovery That Challenges Everything You Know About Drugs and Society (New York: Harper, 2013).

Abbie Hoffman, with Jonathan Silvers, Steal This Urine Test: Fighting Drug Hysteria in America (New York: Penguin Books, 1987).

Jeremy Kuzmarov, The Myth of the Addicted Army: Vietnam and the Modern War on Drugs (University of Massachusetts Press, 2009).

Martin A. Lee, Smoke Signals: A Social History of Marijuana - Medical, Recreational and Scientific (New York: Scribner, 2013). A

lfred W. McCoy, The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drugs Trade, rev ed. (New York: Lawrence Hill Books, 2003).

Dawn Paley, Drug War Capitalism (AK Press, 2015).

Andrew L. Weil, The Natural Mind: A Revolutionary Approach to the Drug Problem, rev ed. (New York: Mariner Books, 2004).

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]