When March 68 in Tunis Preempted the Paris Spring

Two months before May 68 in Paris, the student far Left in Tunisia revolted against Habib Bourguiba’s post-independence régime.

First published in Le Monde. Translated by David Broder.

A Letter from Tunis

Students hanging around in the faded quad, a cup of coffee in hand, and sometimes holding a cigarette. A few small palm trees and a pond lighten its very 1960s concrete decor. It is break time, and everyone is taking a breather between two sociology or literature classes. From the small hill on which the human and social sciences faculty is perched, you can see the banks of Lake Sejumi to the south, where the popular districts of Greater Tunis are clustered. But the university faces east, and most importantly toward the Kasbah, Tunis’s political and geographical centre, a gigantic promenade bounded with ministries on the edge of the medina.

In March 1968, this faculty’s students’ view of the Kasbah, this symbol of the Tunisian state, was such that they broke out in revolt, pre-empting their comrades in Paris by several weeks. The children of "Bourguibism" — following the name of the "father of the nation" Habib Bourguiba — broke out into a frenzy in the same key as youth around the world. The dissent, quickly silenced by fierce repression, left a lasting mark on the Tunisian Left and planted the seeds of democracy. These were events that shaped Tunisia’s unique course.

An Explosive Climate

Half a century later, however, the memory of this event barely survives. "I do not know a lot about this history," sighs Sarah, a literature student with free-flowing hair and fashionably torn jeans. "Here, most students are on the Left because they are freedom-loving," she adds. "On the Left," certainly. But there is a rather weak line of descent from their older forebears from 1968. The transmission of memory from one generation to the next faces the problem of a memory that has been sterilised, its rough patches erased by decades of dictatorship. This loss has not been magically overcome by the Tunisian Revolution of 2011.

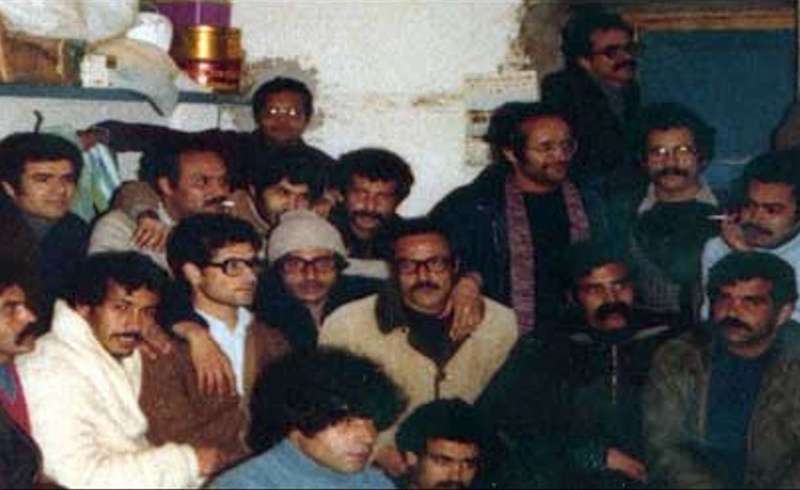

One man was at the heart of this tornado. Khemais Shamari, 75, is an emblematic figure on the Tunisian Left. A portly, chatty figure, this former far Left militant has retained intact his memory of 17 March 1968, the day when the police came to handcuff him in the dean’s office, where a student delegation had come to negotiate. The university had boiled over two days earlier as students demanded the release of Mohammed Ben Jennet, a one-legged student condemned to twenty years of forced labour for his supposed role in the riots — notably targeting the Jewish quarter of Lafayette, in the centre of Tunis — that had taken place during the Six Day War in June 1967.

The Ben Jennet affair was part of an explosive climate. Electrified by international convulsions — "anti-imperialist" struggles, the Vietnam War — and faced with the political-police shutdown imposed by the regime that had emerged from independence in 1956, Tunisia’s youth felt exasperated. In this period Khemais Shamari and his comrades were affiliated to the so-called "perspectivist" movement. This latter was named after Perspectives magazine, published by the Tunisian Socialist Study and Action Group (GEAST), which inevitably developed toward the Maoism of the time. "The agitation began as a purely student movement," Shamari remembers. "Then the Left as a whole got involved, on account of the repression."

Tortured Bodies

One renowned French intellectual had a front-row seat for this Tunisian March 68. Michel Foucault, at that time guest professor at the Tunis Faculty of Letters, later recounted how struck he was by the Tunisian students’ commitment. Here he saw a "moral energy," a "radical intensity," an "impressive drive," a "remarkable existential act," "evidence of the necessity of myth," and "a spirituality." For Foucault, the struggles that played out in Paris’s May 68 "in no sense entailed the same costs, the same sacrifices" (interview with D. Trombadori, Il Contributo, January-March 1980).

Khemais Shamari and his friends did indeed make very great sacrifices. After being put in prison, they were tortured. In the jails of Burj Al-Roumi near Bizerte, where the political prisoners were packed together, their bodies were tortured with a variety of instruments of abuse: the "seesaw," the "parrot board," the "roasted chicken," or the "punching ball." Shamari remembers how the day after his arrest the torturers seemed obsessed by one detail in particular: "as they beat us, they kept asking, 'Where’s the typewriter? Where’s the typewriter?'"

In the wake of the student revolt of 1968, the authorities searched for new bases of support. An Association for the Defence of the Quran was created. Though Bourguiba embodied a secularising "modernism" with some panache, he sought a counterweight to the revolutionary Left and allowed the emerging Islamist movement to gain territory. There were sharp clashes between leftists and Islamists in the university from the late 1970s onward.

Legions of "Eradicators"

From that resulted a mutual suspicion that would endure even when Ennahdha, the party preaching political Islam, was in turn severely repressed by Ben Ali’s authoritarian regime in the 1990s. The Left provided robust legions of "eradicators" (the partisans of "eradicating" Islamism). It was not until the 18 October 2005 Collective, resulting from a hunger strike that brought together certain militants from both sides of the opposition to the dictatorship — the Left and the Islamists — that this split was partially overcome. This split would again emerge after the Tunisian "spring" when Ennahdha, winner of the elections to the National Constituent Assembly, ruled the country from late 2011 until early 2014. It presided over a securitarian climate marked by the rise of radical Salafism.

So what is left of Tunisia’s March 68 today? Apart from a tense or even hostile relationship with political Islam, the heirs to the student revolt have, in Shamari’s analysis, explored "new themes that civil society will later make its own." These themes include the fight for human rights — a number of former "perspectivists" have combined in the Tunisian Human Rights League (LTDH) — and the feminist struggle.

At the human and social sciences faculty in Tunis, the students on their coffee-cigarette break may not be able to name the stars of 68, who fifty years ago renamed the site of their general assemblies "Red Square." But they remain the heirs to these forebears, even if this remains unspoken.

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]