New Forms of Struggle: Selections from Intercontinental Press July 1968

Articles from a July 1968 edition of Intercontinental Press — on the French May, the Prague Spring, and repression in Greece — register the immediate response of the Fourth International to some of the political upheavals that defined that year.

Founded as World Outlook in 1963, Intercontinental Press was a news magazine of The Fourth International, edited by Joseph Hansen of the US Socialist Workers Party, and published until 1986.

Below we present selections from the July 29, 1968 edition, which register the FI's immediate response to some of the political upheavals that defined that year. The majority of items here concern the May events in France — a postmortem interview with Pierre Frank of Parti Communiste Internationaliste and Alain Krivine of Jeunesse Communiste Revolutionnaire; a summary of a Le Nouvel Observateur article on groups to the left of the PCF; a response to the PCF's official assessment of the May uprising; and notes on the experience of the The Citroën Action Committee — but they also include articles concerning the debate on workers democracy then taking place in Czechoslovakia during the Prague Spring and the brutal repression of the resistance movement in Greece.

Czechs Debate How to Establish Workers Democracy

[An example of the kind of debate and rethinking of basic socialist principles now going on among Czechoslovak workers and students, which the Soviet bureaucracy finds so frightening, is provided by the following article, the first of a series by Professor Zbynėk Fišer. It appeared in the June 14 issue of the Czech daily Nova Svoboda.

The second article in the series was published in the Czech left opposition bulletin Informační Materiály of June 24. (A review of the other contents of this interesting new publication appears on page 658.) The editors state that further installments in the series are to follow.

The translation is by Intercontinental Press.]

Now, at last we have gotten to the point of discussing (though not yet of putting into practice) the prime element in the democratization process — workers self-management. From its inception, the Marxist concept of socialism was directly based on the idea that workers self-management in the factories would be the foundation of workers power in the economic and political spheres.

Thus, it is quite understandable that the demand for workers self-management should arise again today in our present stage of development. This stage is characterized by an attempt to carry through a process of democratization and to create real socialist democracy, which must be defended equally against conservative elements and antisocialist tendencies.

The demand for workers self-management cannot be understood abstractly. Everyone bows that today even the Gaullist government is promoting the idea that some form of ostensible workers self-management must be instituted. The meaning of workers self-management differs fundamentally according to the social system in which it exists.

A not unimportant historical experiment — the Yugoslav — has shown that where the market economy and its needs predominate — that is in the conditions envisaged by our new economic system [I.P.: The economic system advocated by Professor Ota Sik, which is based on economic decentralization and use of the "market" mechanisms to regulate the economy] — workers self-management institutions quickly became pliant tools of technocratic management, that is of the plant managers. Moreover, it is not true that in the structure of Yugoslav society the plant managers' interests automatically coincide with those of the real workers.

The Yugoslav factories are supposed to be run in accordance with the wishes of the self-governing workers. However, plant managers fire workers by the thousands in order to step up labor productivity. They keep quiet about the increased unemployment in the country. And they say nothing about the exporting of workers, which from the standpoint of the YugosIav state, has become one of the main means for reestablishing the balance in its foreign currency account.

In our circumstances, the program of workers self-management must have a totally different content. We must clearly understand that workers self management cannot be a merely formal institution. We must not forget that for Marx the principle of workers self-management could only be effective once the entire political system of the society was in the hands of the workers, or rather of their political representative, which could be none other than a truly revolutionary party.

At the present stage of development an important problem is beginning to be posed. The question is whether, above and beyond the demand for workers self- management, a demand should be formulated also — if only as a first step — for effective guarantees of the right to strike. In fact, if the new economic system proposed by Professor Sik is put into practice, the workers would be left with no social guarantees. (This problem was correctly handled by Robert Kalivoda in the Prague party conference. Cf. Rudé Právo, May 5,1968.)

Guarantees of the workers' social rights must be firmly demanded. Indeed, without guarantees that the workers' economic interests will be satisfied, there can be no guarantees either that their political interests will be realized. Democracy as well as political and civil liberties which are not based on real satisfaction of the needs and vital interests of the broadest strata of workers can be neither stable nor lasting. This democracy and these freedoms would be only for socially privileged groups; they would not be the real freedoms expected from the democratization process. They would be only a liberal caricature.

Democracy handed down "from above," democracy which did not strive to stimulate the maximum activity and initiative of the broadest strata of the population could never maintain itself; it could never deliver the results everyone demands from today's rebirth. The party's Central Committee posed the question of socialist democracy too casually in presenting it as a problem which agitates the Czechoslovak people as a whole. In fact, at the moment what we see primarily is stepped-up activity by disoriented liberal groups, which represent minorities in the society.

Workers self-management is certainly an essential precondition for building socialist democracy in all our society. However, it can obviously accomplish very little by itself alone. The workers must have a genuinely revolutionary working-class party. Only such a party can represent the interests of the broadest mass of workers. We are afraid that the process of developing real socialist democracy will be blocked until the top party bodies rid themselves of all their conservative elements.

In order to be able to defend ourselves effectively against attacks from right wing elements, which reflect the views of only a tiny minority of our people, the party leadership must represent first of all the interests of the working class. The establishment of workers self-management could effectively further this goal.

There is a real danger that workers self-management can become camouflage for the manipulation of the workers by the management. Our own experience has shown this (for example, what became of the unions!) as well as the experience of Yugoslavia and Poland. In order to prevent this from happening here, thought must be given right now not only to forms of workers self-management but also to forms of workers self-defense.

Parallel to the program of building workers self-management and parallel to promoting initiative and creative effort to develop a real socialist democratization of society from the ground up — that is, based on the broadest strata of workers, white-collar workers, intellectuals, and peasants — we must strive to create strike funds. This is already being done in the most advanced plants.

There is no doubt that workers self-management based on the principle of the broadest democracy and endowed with the most extensive and effective powers is the foundation of the socialist system as it was understood by Marx and Lenin. However, it is not a providential remedy because in itself it does not settle the question of state power.

This question can only be resolved by a revolutionary organization of the working class. Such an organization must be developed.

May 30, 1968

The Role of the Trotskyists in the Revolutionary Explosion in France: An Interview with Pierre Frank and Alain Krivine

[The following interview with Pierre Frank and Alain Krivine was obtained by Joseph Hansen, editor of Intercontinental Press. Ernest Tate of London and Sirio Di Giuliomaria of Rome also asked occasional questions.

Pierre Frank is a leader of the Parti Communiste Internationaliste, the French section of the Fourth International. At the time of the interview, in June, he had just been released from prison by de Gaulle's political police after a three-day hunger strike.

Alain Krivine became known internationally during the French social upheaval in May as a leader of the Jeunesse Communiste Revolutionnaire and a prominent figure in the student demonstrations that touched off the general strike. On July 16, he and his wife, Michele, were seized by the political police and are at present being held incommunicado in a police camp outside of Paris.]

Joseph Hansen: I should like to begin by asking Pierre Frank what his opinion is on the feeling among the workers at present, now that they have gone back to work, the general strike is ended, and the big events seem to be over.

Pierre Frank: The strikes came to an end barely a week ago. So it is a bit difficult to draw hard-and-fast conclusions. Nevertheless, my opinion is that among the working class in general the feeling is that they made gains in their standard of living beyond anything seen in years and years.

Especially the lowest paid layers of the working class gained a very substantial increase in wages, I think about 15 or 16 percent. Those layers feel that they won a victory.

However there are layers of the working class that feel the strike could have been carried much further, securing not only economic benefits but political gains. They feel that the upsurge could have toppled — if not the capitalist system — at least the de Gaulle regime. And these layers, which are not insignificant in size, feel disappointed — cheated in the outcome of the battle.

Hansen: What is the feeling among the students?

Frank: Some students who became caught up in the struggle are now reverting back to a bourgeois outlook. But I think these are only limited layers. Great numbers of students were won to the idea of socialism, to the socialist revolution, and I think that it would take many years and a crushing defeat of the masses to re-establish the old order in the universities. So while we cannot know exactly when the movement will start up again within the working class, we can say that as soon as the university resumes, that is, next fall, the students will go into action again.

Hansen: Alain, what do you think about the situation in relation to the students?

Alain Krivine: I think that disillusionment is much greater among the students than the workers. From the beginning the students felt that more was involved than university reform. They felt that they were waging a political struggle to overthrow the regime. Today, they feel betrayed.

Of course, this is nothing new for the vanguard elements. But tens of thousands of students first became politically aware through the movement; and now for the first time they feel that the big workers organizations and unions betrayed them.

As a result there is an extremely violent antagonism among the students toward the Stalinists and the Social Democrats and the unions they control. This feeling can often take very ultraleft forms, but it is a general sentiment.

Moreover, there is a feeling not of defeat but of more bitter betrayal because at the present time the repression is aimed essentially against the students. The students' resentment is especially strong now because the police are occupying the universities one after the other without any reaction from these parties or unions.

My impression is that since the students have gained so much experience and shown such combativity that they are only waiting for the opportunity to renew the fight. On this, I agree with Pierre.

Sirio Di Giuliomaria: What did the high-school students contribute and what was the relation between them and the university students in the struggle?

Krivine: One of the most interesting things about the student movement was that for the first time the high-school students mobilized. Their movement developed prior to the May mobilization with the organization of the Comit6s d'Action Lycéens (the CAL) [High-School Action Committees].

Before May these committees existed mostly in Paris and a few provincial cities. They comprised a few thousand high-school students. But in the course of the May mobilization, they spread to most of the cities in France.

The linkup between the high-school students and the university student movement developed in the streets. For example, the high-school students managed to bring 10,000 Parisian high-school students to a university student march at the Place Denfert-Rochereau.

A great ferment developed in the high schools which led to a revolt against the whole administrative setup in the high schools, the whole hierarchy of teachers and administrators. Now, as a result, even the administration has been obliged to take account of the CAL and to completely change the old relationship between the administration and the students. And in those high schools where the students went back just before the vacation, very important changes were made, essentially in regard to discipline.

Next year, for example, I do not think it will be possible to hold the baccalaureate examination in the same way it was held this year or the preceding year. Because we have seen high-school students occupy not only classrooms and the rest of the high-school buildings but also the rooms of the director and headmaster. We have seen them set up infirmaries and even nurseries in some of the schools to help the married university students. That is, they, in fact, established their own control over the high schools. And, in my opinion, this represents an advance which no one can challenge at the present time.

Hansen: Before going into this in further detail, I would like to return to consideration of the attitudes of the classes in a broad way. What is the reaction of the middle class?

Frank: On the middle classes we have not yet had a clear indication. The elections will probably provide this. No doubt a part of the middle class has shifted back to the right. For a time the middle class was carried away by the movement. Especially in what is called the "new middle classes," big shifts have indicated opposition to the old traditions and institutions of bourgeois society.

If we include the teachers, the university professors and high-school instructors in this, a very marked left tendency is apparent. And these layers are very highly developed politically. They may be confused on line but not on their attitude towards the government.

Hansen: And the bourgeoisie?

Frank: For the French bourgeoisie, for French capitalism, it's a big problem to swallow all these wage increases, and just when the Common Market is going to be opened. So what will they do? I think they will try to avoid a too quick increase in prices, because they understand they can have a very sharp reaction from the working class if in a few months they lose everything they gained.

Besides that, there is the question of competing on the world market. So I think they will try to block too steep a rise in prices and also try to avoid devaluation of the franc.

But whatever measures they undertake, they will be faced with a situation where the concentration of capital will increase very rapidly. Small firms will have to close down. There will be many bankruptcies and then we will come to another problem — unemployment.

Hansen: Which area of the working class will be most affected by this?

Frank: Definitely, the young workers. I think the young workers will be the first to suffer. Of course, it depends somewhat on where the plants are located. Some of the industries will be hard hit.

Hansen: What about de Gaulle's policy? How far do you think he will go in attempting to strengthen the ultraright tendencies in France?

Frank: I think in this matter de Gaulle is trying to build a counterweight against the working class. That's why he freed people like Salan and others. He wanted the votes of former pieds-noirs and sectors like that. But I doubt that he will go so far as to open a general offensive against the working class. There are people who think the turn is now towards fascism but I think this is totally wrong. There is no reason for the French capitalists or for de Gaulle to declare war on the CP and CGT. Those organizations were the most helpful in stopping the working-class movement and preventing it from overthrowing de Gaulle's regime. Why should they smash those organizations as such?

I think it is more probable that de Gaulle will resort to a harassing policy against the revolutionary vanguard and against the best militants in the CP and the CGT who try to respond to the aspirations of the working class. So I think that in the coming period the repression will be aimed against the vanguard elements to prevent them from developing, from organizing, consolidating, creating a revolutionary minority which could play a very important role in the future struggles. That is de Gaulle's line. And, of course, there will be attacks of various kinds in addition — not exactly fascist groups trying to smash the main organizations, but doing their best to strike at militant sectors of the working class.

Hansen: What about the possibility that such a course might pave the way for an outcome like the one in Greece, that is, a military take-over?

Frank: You cannot of course theoretically exclude such a perspective. But as I see it, this is not the most probable variant and not even the most, I would say, rational one for the bourgeoisie. Why should they engage in such struggle against the working class which is very strong, not demoralized, and which is so well organized? Its main forces are under the control of the CP and the CGT. Why should they compel the CP and the CGT to defend themselves in a way that could cause them to go further than they want? It seems to me it would be irrational from the point of view of the bourgeoisie. Of course, we can say that in the coming period there may be repeated waves of struggle and maybe after three or four waves — if they should fail to achieve socialism — demoralization could set in on such a scale as to open the way to fascism.

But for the time being, it seems to me that we are in the phase of a bonapartist regime which right now has shifted to the right to find support against the left whereas in the past it sought support on the left against the right, when the right wanted to find a solution in the Algerian war.

Ernest Tate: One of the causes for the crisis was that the traditional parties of the working class were unable to hold the working class in check. Won't this inability lead the bourgeoisie to decide on taking strong measures?

Frank: You cannot say that the traditional parties were unable to check the working class. They were unable to prevent it from going into action. The movement started spontaneously and for many weeks it was beyond the control of the traditional working-class organizations. But they finally managed to establish control.

It is true that the bourgeoisie are alarmed by all this. What alarms them is the development of a strong revolutionary minority of a scope that is still hard to estimate. And they recognized that part of the population — the youth, the students, both university and high school, and also a big part of the working-class youth — got out of control and that alarmed them. And I think that they will of course turn to some use of the fascist-type gangs.

They also have what they now call the Service d'Action Civique which is an organization controlled by the Gaullists. It includes the riffraff, the worst part of the population, and they will use this in attacks. Last week, there was a small incident that is revealing. During the electoral campaign some fights occurred between the Gaullists, who were putting up posters, and the railwaymen in the Gare St-Lazare. They used guns, shooting against the workers.

Immediately there was a reaction. The Gare St-Lazare, one of the most important railway stations in Paris, was closed for three or four hours by the workers.

Hansen: One more question about the regime. For a time during the May events, especially in the last week or so, the regime seemed to be suspended in midair. Now it appears to have regained some strength. But the question remains, how strong is this regime in reality? What is your opinion on that?

Frank: It is true that in the last week of May, say from May 24 to May 30, the regime almost collapsed. There was nobody in the ministries. More important, the forces of repression were on the verge of disintegrating. The Paris police did not want to continue fighting. As a matter of fact, they were not used in the last two weeks against the demonstrations. They even threatened to strike.

One reason was that the Gardes Mobiles and the CRS became exhausted by the constant mobilization.

In the army, it would have been almost impossible to use the troops with perhaps the exception of some paratroopers and special armored corps. I have even heard that the Foreign Legion itself could not have been mobilized against the working class. We could not say, however, that the bourgeois state collapsed. That would be an exaggeration.

Hansen: What was your experience in this, Alain?

Krivine: In the days Pierre spoke about, such a situation indeed existed. In the Latin Quarter, even traffic was directed by the students. For three weeks there was not a single policeman in the Latin Quarter.

During the CGT demonstration in Paris, that is at the height of the mobilization, traffic in the rest of the capital and on most of the main highways leading in and out of the capital was directed by union stewards wearing green armbands. There were no police around.

Furthermore, there was not just disorganization in the police forces but a crisis. We saw a communiqué issued by the Paris policemen's union as well as the Marseille policemen's union asking the government not to put them in a position where they would have to repress the population. They even added that they had demands identical to those of the people and that they might go on strike.

I think that regardless of the election results, the government remains relatively weak. Of course, part of the bourgeoisie has now regained its confidence. But the most dynamic part of the workers and students, and even those workers who voted for de Gaulle, feel that the problem will not be settled by elections but in the plants and in the streets.

Hansen: Pierre has already indicated that he thinks the workers may resume the struggle when inflation catches up and begins to wipe out the gains that they have made. What will impel the students into action, Alain?

Krivine: I think that the student struggle will proceed on two levels. At the beginning of the school year, there will be an initial battle, not to legalize but to force recognition of a whole series of gains established during the May–June mobilization. That is, the students will fight for the right to carry on political activities in the universities and possibly to occupy administrative offices and university facilities in order to hold meetings and organize discussions.

This fight will not be an easy one, in my opinion. We already have an example. At the start of the Nanterre movement, the students forced the dean to allow meetings in the university. But toward the end of the first phase of the Nanterre movement, that is before March, the dean took back little by little all the rights he had granted the students.

The second battle, which is linked to the first, will be a battle over reform of the examination system. In my opinion, there is a danger that this fight may get the movement bogged down, inasmuch as it can be easily diverted by the reformists, helped along by the teachers unions and the Communist Party. That is, it is possible to get petty reforms which will not fundamentally challenge the underlying structure of the examinations nor the existing relationship between teachers and students.

Finally, there will be a new battle which has been provoked by the government. The ban on the "dissolved" organizations cannot be enforced in the universities. These organizations will reappear there legally and publicly. This is a question of principle and I do not think that the students will give way on it.

The open presence of the banned organizations will be an argument for the police to intervene and reoccupy the universities. You can be sure that the first battle after the resumption of classes will be over the right of the dissolved organizations to hold meetings in the universities. This right is essential if only because the "dissolved" organizations are the only left organizations that have any influence in the universities. Thus, this question will be one of the main themes of the student struggle.

Di Giuliomaria: You spoke about reformist maneuvers in the field of the schools. Do you think that this could endanger the student movement in the near future?

Krivine: Yes, there is a certain danger, but not for the vanguard. We have had this experience. When the workers movement started to become political and to advance political demands, while the students were already very highly political, there was a reformist maneuver. The Stalinists, helped along by part of the teachers unions, explained to the students that their problem was not to struggle against Gaullism. This, they explained, was a matter for the working class. The students' problem was whether or not they would take their examinations in June.

After the period of the barricades was over, which had united, say, from 15,000 to 20,000 students, we saw thousands and thousands of students flood into the occupied universities, notably at Nanterre. These students had not taken part in the barricade fighting. They more or less supported it as a gesture to get things moving politically. However, they were primarily interested in educational reform and most of all worried about whether or not they would get to take their exams or whether they would lose a year of academic credit.

At one time, after the barricade fighting ended, we were overwhelmed by this mass of completely apolitical but somewhat reformist students, who were backed up by the Communist party. For example, we witnessed an extraordinary scene at the University of Nanterre. A more or less spontaneous demonstration of right-wing or apolitical students tried to break into an auditorium occupied by left-wing students, shouting "We want to work! We want to work!" The demonstration was led by the Communist students, had a speaker from the TJEC [Union des Etudiants Communistes], and included fascist students. It took in everything apolitical, right wing, and ultrarightist that you can find in the student world.

Thus, it is clear that when classes begin the Stalinists will play on the theme that since we can no longer hope to overthrow de Gaulle, we must go back to more reasonable proposals, that we must try to get a dialogue with the government and win some changes in the examination procedures, certain reforms.

They will completely divorce the need for these reforms from the fact that, in the last analysis, we can now go much further, given the political consciousness of a large part of the students, who now see much further than this.

Hansen: Why did the Communist Party follow the political course that it did?

Frank: The Communist Party of France wanted to replace the de Gaulle regime but only by parliamentary means. They wanted a government made up of the Fédération de la Gauche; that is, the broadened Social Democracy and the PCF. But they had not reached agreement on the program. And the leadership of the PCF is afraid to replace the de Gaulle regime, whose foreign policy suits the Kremlin, with a regime which, if not pro-American, would be at least less anti-American than the de Gaulle regime appears at present.

So, they did not want to carry the fight too far as long as they had no guarantee on foreign policy from the FGDS. In addition they do not want a revolutionary movement. That is very clear.

Krivine: I think that two very revealing paradoxes appeared in this situation. First, we saw the working class offer power to the Communist Party and the FGDS and we saw them refuse to take it. The second thing, which is also a paradox, is this: we can say that out of the ten million workers who took part in the movement, three-fourths probably voted for Mitterrand for president [in 1965], and yet not once in any demonstration did they shout "Mitterrand to Power!” although they had voted to put him in power in the last presidential election.

It is obvious that the Soviet Union prefers de Gaulle to Mitterrand. But I think that it is primarily French conditions, the dynamic in which the Communist party is enmeshed, which explains the positions it has taken.

That is, the Communist Party does want to put Mitterrand in power. But it wants to do this by votes and not by barricades. The CP knows perfectly well that if the workers movement imposed a government in such circumstances, it would no longer be able to keep a rein on this movement's development. And it knows that in such a situation, Mitterrand would play the role of a Kerensky. This fact was uppermost in their calculations.

Now, a final point. We must note the special role the Communist Party played. For a whole period it stepped down as the party of the left, as a political party. It left the leading role to the CGT. For, as this union itself explained, a union does not have to raise political questions. It need only concern itself with economic demands.

Thus, the Communist Party intervened only twice in an independent manner and as a political party distinct from the CGT. On the announcement of the referendum, the CGT did not take a position. The CP, however, took an independent stand, explaining that it accepted the referendum and would campaign for a no vote. The CP's second political intervention came with the announcement of the legislative elections. That is, the CP intervened as a political force only in the electoral realm.

Frank: I think that the movement of May 1968 has shown that the CP has reached a new stage. During the war, the CP carried on a long, illegal struggle and many of its militants were victims of the Nazi repression. But after that, the CP entered the government. It was ejected from the cabinet but it still held many positions and the party became still more corroded. Its leadership is not much different from the Social Democratic bureaucracy.

This party is now a very legal party in the bourgeois-democratic sense of the word.

Hansen: The Communist Party and the Social Democrats were to a certain extent bypassed in the May events. They did not call the general strike. They did not organize the demonstrations leading up to it. Other forces moved to the forefront.

One of the particularly interesting aspects of this is that small groupings appeared to play the role of a "detonator" and this has caught the imagination of many students and young people throughout the world. They are interested in the "detonator" and some people are beginning to draw theoretical conclusions about it.

Could you explain to us exactly what happened in the May events in this respect?

Frank: If I'm not mistaken, in the H-bomb you start the explosion by a small atomic bomb which acts as a detonator. I think the situation in France worked about this way. There was great discontent among the masses, but something was needed to start the explosion. This came through the rebellion of the students. Obviously, in every revolution you see something like this. The social tension increases and somewhere a link snaps.

Hansen: Did the Trotskyist youth plan to detonate a general strike involving ten million workers in May?

Frank: No, that was out of the question. Nobody thought that we could do that with the precision of a physical science. It occurred; but it was not calculated.

Hansen: Do you think it could be repeated? For example, could the students select a definite date for an action that would in turn lead to a general strike?

Frank: Certainly not. The students could perhaps engage in big actions. That doesn't mean that the working class will react. In May it happened. The conditions were there.

Hansen: What do you think of the tendency among students in other countries to develop a theory on this — that by engaging in actions like the French students they, too, can detonate a tremendous movement?

Frank: As a theory, it seems to me wrong. It can succeed if the conditions are there; it won't succeed if the conditions are not there.

Hansen: Would you agree on this, Alain?

Krivine: I agree. But I think that there is a double danger. There is a danger of overgeneralizing the experiences of the student struggle, of making theories based on them after the style of Marcuse. But I think there is also a danger of bypassing the problem and saying: "The students played the role of detonator in this case, but this was an accident and tomorrow the spark could come from a factory or from somewhere else."

We must recognize that there were movements of revolt in France in the recent period which showed great discontent among the workers and which the working-class organizations were no longer responsive to. For example, in the riots in Caen, in le Mans, in Mulhouse, and in a whole series of cities, we saw especially the unorganized young workers launch very violent movements. But these revolts did not spread.

But when we look at the situation in May we see — and I am not making a theory, I am just describing the reality — that the students played two roles. First of all, they played the celebrated role of detonator. But later on they also played the role of a radicalizing agency.

That is, once the students had touched off the movement, once the workers movements had joined in the struggle and attained a certain political consciousness, the students organized demonstrations which served as a politically radicalizing force and again enabled the workers movement as a whole to move on to a higher stage. After the rally in the Charléty stadium, where there were about 50,000 people, 20,000 of them workers, the CP was forced to call a demonstration around totally different slogans, “A People’s Government!”

None of us had foreseen that the student movement would set off an insurrectionary general strike of ten million workers. However, we had seen the experiences of the German SDS and of the Italian student movement. We had seen that first of all the students were able to draw into their struggle young workers discontented with their political and union leaders, and, secondly, that they could produce a political crisis, I won't say of the system but at least of the government. That is, we thought that the student movement could carry out actions which could serve as a model of struggle for the discontented young workers and bring them into the fight. The only thing that we underestimated was the breadth that we could achieve.

What happened in France and what is happening in Europe can be explained this way: the mounting working-class discontent could not find an outlet on the national scale because of the weight of the bureaucratic workers organizations. Normally, only these organizations could give broad scope to a movement of revolt. And we saw in France, especially in the struggle against the social security cuts, that they did not want to do this. Therefore, only a national vanguard organization could extend the movement. However, such an organization does not yet exist in France.

On the other hand, the student movement as such, once it had developed a base and sufficient numerical strength, was able to become a national political force and offer a nationwide political example. Thus, for a certain time it could substitute for the missing vanguard.

What impressed the majority of young workers who joined in the struggle, as we have pointed out, was not the student movement's demands. For example, police occupation of the Sorbonne means nothing to the workers. What they borrowed from the students was their new forms of struggle — direct action. And the lesson they learned was that the government yielded to these new forms of struggle. Once the workers had seen this, the student movement could play its role.

Thus, I am not saying that the student movement can serve to touch off revolutionary situations in all cases. That would be an idiotic and extremely dangerous notion. What I am saying is that in view of the character of the working-class parties and the fact that the discontented young workers are more and more alienated from the trade-union and political leaderships, the student movement can serve as a partial detonator, perhaps on a national scale. And I am saying as well that the student movement can appear as a pole of political radicalization, as an example of what can be done at the practical level and not just in theory.

Hansen: The JCR, of course, was recognized by most of the bourgeois press as playing a leading role in the events during May in the student movement. Did the JCR experience a corresponding growth in membership, in real weight as an organization?

Krivine: As a consequence of the May mobilization, the JCR made important gains both in membership and in influence among the youth. These gains were not related to the publicity we got in the international press, because the JCR members did not read these papers. Our gains were a result essentially of the way the JCR intervened in the movement, as opposed to the way the other vanguard groups went about it.

From the start, the JCR fully integrated itself in the movement, even though we were aware that the forms the student movement was taking were extremely provisional. We realized that these forms, that is, the anti-leadership, spontaneity-worshipping, sometimes anarchistic aspect of the movement, could not last without threatening to get the student struggle bogged down. But we thought that the movement would develop as a result of the students' experience and by our posing political problems and the need for political organization. And this is what finally happened.

Conversely, this development of the student movement also explains the decline of all the anarchistic currents. At the beginning, all these currents were perfectly integrated into the movement. This was so essentially because, at the start, the reality of the student movement seemed to fit their theoretical prescriptions about the lack of a need for organization. However, the movement soon went beyond them, and this was the reason for the decline in the influence of the political positions of some comrades, like Geismar, or Cohn-Bendit.

To take up our gains more concretely. In Paris, for example, the JCR doubled its membership during the May–June mobilization; and it was the same in many provincial cities.

But aside from this very intensive recruitment, what was much more important for us was the hearing we were able to get before thousands, tens of thousands of youth. This means that when classes resume we will be the strongest left political organization in the high schools and universities, stronger even than the Communist students.

What is also important is that the May–June mobilization enabled the JCR to begin to acquire roots in some plants and to recruit a much larger number of worker militants than in the past.

Also the May movement made it possible for us to have an impact on adults, both among adult workers and among the middle strata. We must find organizational forms by which to take advantage of this new influence.

Finally, one last point. Up until now the JCR has been known as the youth organization with the most experienced cadres, both on the level of political education and practical experience. For these cadres came out of a factional struggle inside the CP and this contributed to their political training, teaching them how to be mass leaders and carry on a certain level of mass activity. It is obvious that the JCR has emerged from the May mobilization much more seasoned than in the past. And so there is every chance for the JCR to double or triple its membership in the corning months, despite the ban.

Tate: I would like to know how the previous activities of the JCR led to it being placed in the position it was in just before the explosion, so that it could take advantage of the situation.

Krivine: There were two things which were interconnected: the political activity we carried on and the political explanations we gave. As I just said, the movement did not come as a surprise to us. We had anticipated it and we even fought against other political groups on the basis of this perspective.

For example, last December there was a demonstration organized by the student federations which included thousands of students who showed a combativity not seen in the student world for many years. At that time, the police prevented the students from entering the Sorbonne. We decided to go into the Sorbonne and start a fight to achieve this aim. We explained to the students that we were in the middle of a period of working-class struggles because of the ferment over the social security cuts. We explained that a strong demonstration in the Latin Quarter would have meaning and could unleash something in the country.

We put it down in black and white at the time in an article in L'Avant-Garde, notably to refute the position of the Lambertists. During this demonstration they interposed their stewards between us and the police in order to avert a clash, explaining that students should never fight the police alone. Without the help of the workers, they said, the students risked being crushed.

A second extremely revealing example came on Easter Sunday this year, in the middle of the vacation. Two days after the attempted assassination of Rudi Dutschke, we organized a demonstration in front of the German embassy and in the Latin Quarter where we got a thousand students — in the middle of the vacation! And there for the first time in many years there was a clash with the police. The French students never fight the police. They never stoop to the material, or counter the police in a material way. Although this fight lasted for only a quarter of an hour — for just one quarter of an hour — the students used everything material they could get their hands on — garbage cans, chairs, bottles. This had never been seen before in the student world.

What enabled us to develop a base among students but also among adults was that we were already known before the May mobilization. The preponderant role we played in the Comités Vietnam Nationaux (the CVN) [National Vietnam Committees] is having its effects today. It was after our intervention in the CVN that we acquired a mass following among the students. Neither the Stalinists nor the Lambertists did anything on Vietnam — absolutely nothing.

We founded CVN's and we organized demonstrations in the name of the CVN which sometimes brought out 6,000 to 7,000 students in the Latin Quarter.

And this Vietnam activity made it possible for us to gain a hearing in the adult world. The CVN’s which were organized in the neighborhoods formed the core of the action committees which developed in the various neighborhoods of Paris during the May days.

We came in contact with more militants through the CVN's than through any other mass activity we carried on, whether in the unions or elsewhere. And it is this work, I think, which explains our success.

Hansen: What about the Internationalist Communist party, the French section of the Fourth International — how was it involved?

Frank: At first it was a student rebellion. Then came the general strike. The trade unions played a bigger role in this than the parties. This was because of the Stalinist policy. But there were additional reasons why the political issues came to the fore only at particular moments.

The PCI is composed mainly of young people, many of whom also belong to the JCR. The party itself was very active. This is indicated by the daily bulletins and leaflets. I don't think we made any mistakes on the political line and day-to-day tactical problems. Our activity, of course, was limited by our forces. We worked day and night. The roneo was turning day and night. But that doesn't carry very far when you have a movement of ten million people on strike in the factories.

We did our utmost and of course now we are accused along with other "groupuscules" of being responsible for the movement. We'd be very proud if that was so because if we had been in charge it would have finished in another way.

Hansen: Maybe you'd say a few words about some of the other groups that were involved, For example, Voix Ouvrière.

Frank: In France in the last period we could say that the Trotskyist movement was composed mainly of three groups: the French section of the Fourth International, the Voix Ouvriere group, and the Organisation Communiste Internationaliste, or OCI, more commonly known as the Lambert group. This is the group connected with Healy in England.

We could say that the three groups were each of almost equal size and had equal audiences, though the audiences were not exactly the same. I mean in the sense of the social layers or milieux where they were working.

The Voix Ouvrière group had no youth organization although students belonged to it. They concentrated their work in a systematic way in the workers' milieu. I have read in Healy's paper an article criticizing the Voix Ouvrière for their role in the movement. Healy's paper used an article written by Voix Ouvrière about two or three weeks before the May events. I must say that the article was not exactly good; but we do not judge people so much by what they say as by what they do.

When the movement started, the comrades of Voix Ouvrière understood very quickly its importance. They participated in it and integrated themselves in it. We cooperated with them and the JCR and formed a coordination committee. It was mainly on practical matters; but we also cooperated in putting out a leaflet together. I think that fraternal links were strengthened by being together in the battle and also being under arrest together.

Hansen: Towards the end of the upsurge, I noticed that the followers of Juan Posadas had a literature table at the Sorbonne. Were they involved in the movement in any other way?

Frank: So far as I know, it was only at the last that they showed up at the Sorbonne. But besides the very serious groups at the Sorbonne there were also some crackpots.

Hansen: On the other hand, I noticed no OCI literature table.

Frank: The OCI — the Healy people — they took a very negative attitude toward what happened in the Sorbonne. They called it a "kermesse," a carnival. It's not very different from the "chien-lit" used by de Gaulle.

Hansen: I saw in The Newsletter, the paper you mentioned, that a congress of the Socialist Labour League passed a resolution stating that their allies in France were not cowards in relation to the May events. Maybe you could give me some indication as to the meaning of this. Why would Healy's congress discuss whether or not their French cothinkers were cowards or not cowards?

Frank: First of all, we never called them cowards, and I don't know anyone in France who used this expression. We said that they had a wrong political line — which is something else. They probably found it necessary to defend the OCI and the members of their youth organization, the FER, because of their attitude in this struggle.

Of course, the main incident was their refusal to participate on the barricades on the night of May 10 and 11. Everyone knows this fact. It cannot be contested because their leaders voted on it. It was published in various French papers. They held a meeting that evening. They left the meeting — I don't know how many there were; they say about a thousand. They came to the barricades and told the people there not to stay because it was an adventure; there could be bloodshed; and so on. And they left.

That is the first thing. But I must say it was not just an isolated incident because throughout this period at every decisive moment, for all their fine language, they stood to the right of the vanguard.

For example, a few days later on May 13, they participated like everyone else in the general strike demonstration. But when we arrived at Denfert-Rochereau and the vanguard, the minority groups, decided to continue the demonstration, to go to the Champs de Mars, they refused. As a matter of fact they had the same slogan as the leadership of the CGT and the other trade unions — to disperse.

Also, at the May 24 demonstration at the Gare de Lyon when a fight broke out with the police, and barricades were built, they were against it.

Their whole attitude on this issue has been very negative.

I want to give another example, their attitude on the question of the dissolution of the organizations. They made a statement, published in Le Monde of June 16–17, that they would respect the present laws, that they would not take to the maquis of Fontainebleau, that they were not the Che Guevaras of the Latin Quarter, that the only answer to the ban was to organize a mass demonstration of all the trade unions.

I think we can now see their line very clearly: they speak vehemently against the leadership, the betrayals of the Stalinists, and so on, but they believe that it is sufficient to denounce them, to propose big demonstrations, and to denounce them for not organizing such demonstrations in order to show that they are betraying the working class.

When a big demonstration occurs, as on May 13, they try to take credit for it as being due to their activities over the years. I don't doubt that the activity of militants over the years is very important; but you cannot explain such demonstrations by the years of activity engaged in by them and all the vanguard. It was because there were barricades on May 10 that a big demonstration was held May 13.

If you read their documents, you will see that they speak of the demonstration of May 13 and the demonstration of May 29 — the demonstration of the CGT — but they do not mention the demonstration of the 10th, the night of the barricades, nor the demonstration of the twenty-fourth at the Gare de Lyon. They do not understand that mass organizations are moved not only by proposals and shouting, but also by action. That there are actions undertaken by minorities which can bring the mass of the working class into action and force the organizations to move.

Hansen: I also see in The Newsletter that Healy or one of his writers admits that their allies in France, the OCI and the FER, are rather unpopular among the rebel students; but that this is all right because they followed a correct policy. Is it a fact that they have lost standing, lost influence in these circles as a result of their line, their policy?

Krivine: After the night of the barricades it was almost impossible for them to speak in any of the students' general assemblies. Very extensive democracy reigned in all the student assemblies, anyone could speak. They were the only exception.

The minute any one of them identified himself as an FER member the audience shouted the whole time, "Where were you on the night of the barricades? What did you do on the barricades?" And their answer was always, "We were not on the barricades because we went to prepare the demonstration of 500,000 workers that followed the barricades." That was the only explanation they gave.

I think that they have lost all respect, all influence, among the students and that this will be a lasting thing. This explains why they were the only organization that did not have a table in the courtyard of the Sorbonne. They wanted to avoid being continually attacked by students asking them to explain their actions.

Frank: I think that in the provinces their members did not conduct themselves the way they did in Paris. They acted more spontaneously and they participated — in some provinces they played the role of leaders. But, of course, in Paris and in France as a whole, their line was completely wrong. I may add also that I met some of them when we were arrested. There, relations were very friendly.

Hansen: What happened with the anarchists and especially the March 22 Movement?

Krivine: "Anarchist" doesn't mean very much. There are several anarchist groups. As groups they had no influence. They did play a role in the demonstrations, but because they are very brave people; that is all. It was rather "anarchistic" ideas that were to be seen in the movement. These ideas did not emanate from the anarchist groups; they arose spontaneously from a whole series of conditions.

As for the March 22 Movement, it has lost its initial character as a democratic organization uniting all the left currents of the student movement. When the action committees developed and took over this function, it refused to dissolve into these committees and insisted on keeping up the label of the "March 22 Movement." As a result, all the political elements left it a few weeks ago. Today it includes about fifty Nanterre students and is strongly dominated by an anarchistic wing.

It has practically no following today, except inasmuch as any banned movement does. Because it played a role at the start of the movement the press gives it a lot of play. But it can no longer mobilize many students.

Tate: I would like to ask Alain what has been happening to the Marxist-Leninist groups that participated in the struggle — the pro-Chinese?

Krivine: There are two pro-Chinese groups in France — the Jeunesses Communistes (Marxiste-Léniniste) composed basically of students; and the Parti Communiste de France (Marxiste-Léniniste) composed essentially of adults, often ex-members of the CP.

These two organizations played a certain role in the movement. In the beginning, the Jeunesses Communistes (Marxiste-Léniniste) completely opposed the Nanterre movement, explaining that it was a one-hundred-percent bourgeois movement. However, later on they made a total self-criticism and joined the movement.

In general they took little part in the student struggle. They left the universities and went to the factory gates to capitalize there on what had been accomplished among the students. They had a few successes in certain factories but because of their dogmatic policy and their way of intervention they usually very quickly lost the contacts that they had been able to make.

Furthermore, their progress among the students was limited because of the way they conceived the relationship between the students and the working class. The name of their paper [Servir le Peuple — "Serve the People"] sums up their approach, that is to send students to put themselves at the service of the workers. For months they have been sending their students into the factories.

They do have a certain influence today — much more than the FER. However, they are experiencing internal problems. The two pro-Chinese groups are trading members back and forth in their infighting. They are also having programmatic difficulties. They are copying the program of the CP and the Stalinists word for word, trying to give it a different content. For example, throughout the mobilization their slogan was “A Popular Front Government!” They put out a paper entitled "The Popular Front Journal: "A Popular Front Government: For the Victory of the Popular Front."

Hansen: I would like to take up the question of the repression of the various so-called splinter groups, as the government calls them. Pierre, maybe you could tell us something about your experiences with the repressive apparatus in France.

Frank: The repression up to now has taken two separate forms. One was a decision by the cabinet to dissolve as many as thirteen organizations. This decree was signed by de Gaulle, president of the republic, Prime Minister Pompidou, and the minister of the interior. This is a decision banning the legal activities of our movements. They are dissolved. The pretext was that we organized combat squads and a private militia. This is the only allegation. Not a single bit of evidence is cited. Obviously the charge is a lie because none of the organizations organized a private militia or combat squads.

Then the Préfet de Police of Paris issued what is called réquisitions against people who allegedly violated state security. Raids were made on the headquarters of those organizations and the homes of some of the members. And a certain number of people were — I don't know how to translate that into English. We are not charged; we are not accused. We were not held as witnesses. We were "garder à vue" — held incommunicado.

In France under the common law you have the right of habeas corpus. If you are arrested by the police, they have to either file charges or release you within twenty-four hours. In cases involving "state security," this right does not exist. You are kept for two days. Then it can be stretched to five days more, then another three days. This is decided by the prosecution.

So they began by arresting about twenty people to start with.

Hansen: You were held in a cell?

Frank: No, we were not in a cell. We were kept in a large room. Material conditions were acceptable for such a short period. But the problem was that we could not see anyone, neither a member of our family nor a lawyer. You were taken out of the society and you have no possibility to get in touch with anyone. You were held by the police. The Gardes Mobiles were there, too.

And you were lost from society for two days at the beginning, then seven days, then ten days. It is the old, royal "lettre de cachet," when the king of France could put someone in jail for, of course, not ten days, but an indefinite period.

Hansen: What is the situation now regarding the struggle against the repression?

Frank: Perhaps it would be best to begin with the legal situation. Formally, I still have all my civil and political rights. I am able to publish anything, to print anything. The office at the Faubourg St.-Martin is open. It belongs to a publishing house, the Societé Internationale d'Editions,

But the PCI has been dissolved; that is, it's impossible to hold a public meeting of the PCI legally. It is impossible for the PCI to even function internally without falling under the charge of reconstituting the organization.

I think our case is a very good one in the sense that there is all kinds of evidence that the charge was a lie. We have no combat squads and no private militia.

A Comité de Défense has been formed with the preliminary support of ten important figures like Monod and Kastler, Schwartz, and Sartre.

Hansen: This defense group is for all of the different organizations?

Frank: For everyone and not only for the organizations. There are other problems. For instance, this "lettre de cachet” system.

There is also the necessity to defend the foreign workers and militants who have been expelled from France or are threatened with deportation. In one case, we learned that a Tunisian was deported back to his own country and arrested there.

There is also the necessity to defend people who are persecuted but not officially. For example, there are soldiers in the army suffering reprisals because of their attitude during the May movement.

The committee intends also to fight against the brutality of the police, the CRS, during those demonstrations, and they already have a lot of evidence on this.

So there will be a broad defense committee which will start a campaign on all these matters.

Hansen: What can people outside of France do to help in this?

Frank: Demonstrations, protest actions, would help to publicize this situation, this repression, and to demonstrate international solidarity.

Hansen: What has been the attitude of the Communist Party in this respect? Have they participated in this?

Frank: Not at all. Protests have been voiced against the ban by the FGDS, by the Socialist party, of course by the Parti Socialiste Unifié — everybody, including the CFDT. But the PCF and the CGT have not said a single word. Instead, they are still slandering the leftists.

Hansen: One final point. What can be done by Trotskyists or sympathizers of the Trotskyist movement outside of France to help the French Trotskyists at this particular time?

Frank: What we need today most of all is Trotskyist material in French. In May we sold our entire stock of books, pamphlets, and so on. Everything. When the police raided our headquarters, they were not able to cart away much because we were stripped clean.

So that is the first thing. We have to print a lot of things and of course you know that printing costs a lot of money. We need not only the usual small items but books. We have nothing. Everything went.

Fortunately, many of Trotsky's books are still available in paperback, and some new ones will shortly be published. But that's not sufficient. We need a lot of standard Trotskyist material and also new items. That's where comrades abroad can help us very effectively by sending financial contributions. And also we need material help in combating the drive to repress our movement.

Le Nouvel Observateur Looks at the French Revolutionary Youth Groups

Under the title, "The 'Troublemaker,'" Katia D. Kaupp, writing in the June 19 issue of Le Nouvel Observateur, the well-known liberal Paris weekly, offers an interesting survey of the youth organizations whose actions precipitated the profound social crisis that shook France in May and June.

The de Gaulle regime, she notes, called them “splinter groups,” which did not prevent the police from singling them out for special attention nor de Gaulle himself from signing a decree banning them on the eve of the June elections. The bourgeois press branded them with what it rates as one of its most derogatory labels: "Anarchists! And the Communist party brass sneered at them, "Leftists!”

But the students at the Sorbonne viewed them in a much more favorable way. In fact, because of their influence the student world in France will never be the same. This is not to say that the students are uncritical toward the revolutionary youth organizations — they even offer harsh judgments in some instances — yet the general feeling toward the "troublemakers" is completely opposed to the attitudes expressed by the regime, the press, and the Communist party.

The prestige of the avowed anarchist groupings is high among the students. One of the reasons for this is the role played by the March 22 Movement in touching off the chain of events that led to the building of barricades and finally the general strike involving ten million workers. While not dominated by the anarchists, the March 22 Movement was influenced by them and voiced some of their concepts.

The anarchists are very hospitable, writes Katia D. Kaupp. "They don't put up any prior conditions on welcoming you in to discuss. They speak familiarly and you feel at ease. Another good point: they are cultured, although 60 percent of them are genuinely workers...."

Among the groups and tendencies of anarchists, Kaupp lists the Anarchist Federation to which the Revolutionary Anarchist Organization belongs and which publishes Le Monde Libertaire [The Libertarian World]. Certain groups specialize in particular forms of struggle.

Although they were excellent fighters on the barricades, the anarchists drew a sharp line between their objectives and those of the groups adhering to Marxism.

"But watch out!" they said. "As the Federation sees it, we're not going to revivify Marxism... Marxism is the opium of the average proletarian!"

But they believe in revolution. "We'll make the Revolution! ... Only not a Socialist state — socialism."

At the Sorbonne they were known for their black flag. They themselves, however, in accordance with the traditional anarchist view hold it in little respect. "For us, it is nothing but a rag at the end of a pole for us to rally around."

Some of their slogans went right to the heart of things: "We don't give a damn about frontiers!" "All of us are German Jews!" "Down with the police state!

The Maoists, Kaupp reports, took a standoffish attitude toward the March 22 Movement, characterizing it as "100% bourgeois." At a meeting sponsored by the March 22 youth they walked out, only to return and sing the "Internationale, fists raised in the traditional Communist salute. "The UJCML [Union des Jeunesses Communistes Marxiste-Léniniste] of Paris," a spokesman announced, "has decided to leave Nanterre and to no longer help in guarding the school building."

On the same day, the fascist group called "Occident" [West] threatened to attack "the Bolshies of Nanterre" and told the police to get ready "to pick up the wounded who will be lying on the sidewalks of the Boulevard Saint-Michel."

The coincidence between the withdrawal of the Maoist youth and the threats of the fascists did not go unperceived in the Sorbonne.

"But for the UJCML," writes Kaupp, "the important things are not happening at the Sorbonne but in the plants and at the plant gates. 'The students are only petty-bourgeois elements — the flag of struggle is carried by the working class.'" It is true that the ML militants frequent the plant gates — at Javel, at Boulogne-Billancourt, at Flins. The high-school student who was drowned at Flins — and for whom 10,000 youths last Saturday conducted impressive funeral services in silence — the silence of accusation — belonged to the UJCML.

"At first, the UJCML held a meeting every evening on the steps of the chapel, each participant wearing his badge with Mao's portrait. The speakers were always vehement. But soon their activities 'inside' the Sorbonne became limited to no more than selling their newspapers at their table — Serve the People and the daily they got out since the 'events,' The People's Cause; along with, it goes without saying, Mao's Thought, in any number of booklets. The great majority of the 'Chinese' are at the plants. They denounce the 'traitorous' leaders and encourage a struggle within the CGT [Confédération Générale du Travail]. They reject the CFDT [Confédération Française et Démocratique du Travail]. They denounced the meeting at Charléty.” [I.P.: A meeting of more than 50,000persons, mainly young people, representing the most advanced layer in the revolutionary upsurge.]

The author of this account devotes considerable space to the groups claiming adherence to Trotskyism. The great majority of students now distinguish between the two main claimants to this program and ideology. Kaupp indicates the basis of the judgment reached by the students in France on this question.

"In the case of the FER — Fédération des Etudiants Révolutionnaires — you run into the opposite feeling [opposite to the sympathy felt for the anarchist groups]. For them as for all the other movements you have to demand that the ban imposed on them be lifted and that their arrested members be freed. This said, however, their credit in the eyes of the student movement is low.

"These are the Lambertist-Trotskyists; they are directly attached to the Organisation Communiste Internationaliste [Internationalist Communist Organizationl, a split-off from the Fourth International which developed in 1952 as a result of a disagreement between Lambert and Frank. In order to capitalize on the crisis of Stalinism, Frank advocated 'entrism' into the mass organizations — the Lambert faction opposed it.

"Since then other political differences have been grafted onto this one, in particular as regards the 'colonial revolution.' On Cuba, the Lambertist position is that it is a bourgeois state founded by the petty-bourgeois adventurists Castro and Guevara. On the NLF, their position is that it is a creation of the Vietnamese petty bourgeoisie. They refused to sign the 'Appeal for a Billion Francs for Vietnam.'

"It is the first night of the barricades which separates the FER from the movement. On Friday, May 10, at 11:30 they left the Mutualité and set out on a march — about a thousand in number — along the Boulevard Saint-Michel. They stopped halfway [to the Latin Quarter], shouting: 'Listen, comrades, you are heading for a massacre; this is adventurism!' Nobody followed them; it is they who are blamed for not having followed the movement.

"Ever since that night, every time an FER member has tried to take the microphone at the Sorbonne, a voice, voices shout out a question, always the same one: 'And where were you on the night of the barricades?' *

"The FER's slogans have been: '500,000 Workers into the Streets!' 'One Million Workers to the Elysée!' '3,500 Youth to the Mutualité in the Month of June!' and finally and above all, 'United Front!’

"'This is verbal escalation! It's fine to have slogans; it has a revolutionary value. But only if these slogans are picked up by the masses! As for them, they launch slogans the way you launch balloons. Three months later they let you have it in the puss; and then they denounce the 'traitorous leaderships" for failing to follow them...Simple!' This is what many students say who are unconvinced.

"In demonstrations, the FER appears in a phalanx, its members singing at the top of their lungs, and with a squad of monitors that is reputed to be the utmost in efficiency. But at the Sorbonne I had to go looking for them. Third floor, Stairway C. After the first days they disappeared from the courtyard. They are there in the evening, however, all mobilized to hawk their paper: 'For the creation of a central strike committee, for an all-out strike; read Révoltes!'

"Aside from this, 'they only come to other people's meetings to start brawls.' In fact, on the evening of Daniel Cohn-Bendit's return from Germany they tried to take over. The crowd 'cleared them out.' Another evening the whole audience in the big auditorium stood for five minutes, chanting: 'FER fascists! FER fascists!'

"At first you are startled. You don't understand; you wonder why they are considered so unbearable... Their political views are partly the reason but also their style and tone. Their military air, their 'strong-arm' stance, the insults and threats constantly at the tip of their tongues, their affecting the jargon of the workers and the working-class neighborhoods — all that raises the hackles of the Latin Quarter: 'Playing tough guy is all right for the Occident [the West -- an ultrarightist organization] thugs — not for the left."'

Another group avowing adherence to Trotskyism formed around the newspaper Voix Ouvriere, which was likewise banned by de Gaulle, is not mentioned by Kaupp. She does deal at some length with the Trotskyist grouping that received the greatest publicity during the May events, the JCR. Here is what she says about them:

"Finally, the JCR — Jeunesse Communiste Révolutionnaire — the 'competitors' of the FER in the old Trot battle. It is mostly made up of youth previously thrown out of the UEC — Union des Etudiants Communistes — in 1965 for having refused to support François Mitterrand's candidacy. Their paper is Avant-Garde Jeunesse [Vanguard Youth]. With them, as with the 'anars' [anarchists] you can breathe freely. They are good-humored smiling people, 'civilized.'

"'You want to see us? All right, whenever you want. We meet every evening in the Guizot auditorium.'

"A meeting — and posters in all the corridors, everywhere, to inform people of it. Everybody agrees: 'The JCR is doing a fantastic job at the Sorbonne.'

"The Guizot auditorium is — was — packed every evening. There the JCR conducts a ‘course' in history or current events, rather similar to the education the students would like in their colleges. After every session comes the discussion — contagious in its enthusiasm.

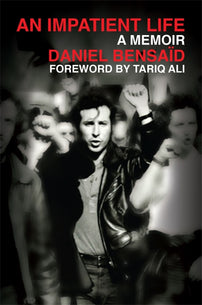

"Alain Krivine, Henri Weber, and Daniel Bensaid take turns. Krivine is a doctoral candidate in history. A warm voice, black mane, glasses, blue suit. In appearance half prophet, half Central European intellectual. Weber is preparing his thesis for a master's degree in sociology. Blue eyes, black hair. Bensaid has a BA in philosophy and is writing a thesis on a topic that is quite apropos: 'Lenin's Concept of the Revolutionary Crisis!' With gold-flecked, mischievous eyes, he is the most relaxed.

"All of them have an extraordinary gift for extemporaneous speaking — what a difference from the prefabricated 'oratory' of our radio-television candidates! And their political knowledge is faultless.

"When they hold a public meeting in the 'big auditorium,' the JCR members on the platform hum the 'Chant des Marais' [an antifascist song] through to the end before the meeting starts. The entire audience then responds, singing the first two stanzas of the 'Internationale.' The impression is already more powerful than in the 'united' marches.

"But a JCR meeting is first of all a work session. Serious, well-documented work without wasted talk. But it is also a display of intellectual fireworks. It is furthermore an open meeting. Anyone can speak, voice disagreement, argue. Respect for the rights of different points of view is sacrosanct.

"They and the March 22 Movement have been the only ones able to fill the big auditorium to capacity. From the aisles to the second balcony, every possible space is taken. Sitting on the floor, standing every inch of room. Like for Sartre!

"From the JCR's founding in April 1966, following their expulsion from the UEC, they have given total support to Vietnam (in particular the CVN [National Vietnam Committees]) and to Cuba — this revolutionary country outside the two blocs and which most clearly rejects 'statist' politics. They participated in the Vietnam demonstration at Liege along with 'traditional' Communists, Social Democrats, and various revolutionary groups (October 1966). And they were at the Brussels International Conference (February 1967) organized by the youth movements standing to the left of the old organizations.

"Three clear basic needs emerged at Brussels: support for Vietnam; struggle against NATO and imperialism; organization of political and practical coordination among the movements.

"It is true; they are revolutionists. They have always said so. They have always declared that the mounting revolutionary wave in the world today poses the question of 'world socialism.' But they have never acted like a gang or a secret organization preparing in the dark to finish off capitalism! Only this: France is a capitalist country, and just talking about socialism is enough to make it tremble. Some ideas are more frightening than guns."

___________

* In fairness, Le Nouvel Observateur ought to have called attention to the fact that the FER is not wholly lacking in popularity. In London at the beginning of June, the delegates at a congress of the Socialist Labour League, the grouping headed by Gerry Healy, passed a resolution which unanimously "applauds the leadership provided by the OCI and the Federation des Etudiants Revolutionnaire... denounces the malicious and lying attacks of the anarchists group 'Solidarity' and the revisionists around the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign," and approves the wisdom of the FER in avoiding being "diverted into a senseless battle incurring needless casualties on the barricades on May 10." To emphasize the enthusiasm felt by this British sect over the tactics of the PER, the resolution added: "Congress contemptuously rejects the allegations of cowardice levelled against our comrades as baseless and the work of provocateurs.''

Perhaps the resolution was too little, or came too late, to influence the general attitude of the students at the Sorbonne. Or it could be that the FER, which considered the entire development at the Sorbonne to be nothing but a "kermesse" [country fair], did not care to contribute to the festive atmosphere by distributing a translation of the historic document. This would account for the Nouvel Observateur not knowing about it, a possibility that should be borne in mind in judging their failure to report it.

The French CP Draws Its Balance Sheet of the May–June Events

by Pierre Frank

The Central Committee of the PCF [Parti Communiste Français — French Communist Party] met July 8–9. On its agenda were the events which took place in France in May and June. After the two days of deliberation, it was learned that the Central Committee had approved the actions of the Political Bureau during these events, voting unanimously for a resolution which was a condensation of Waldeck Rochet's report.

Only the long report was made public, nothing was said about the discussion. All the party members are equal but some are more equal than others. Democracy is a feature of the Communist party's propaganda, not of its life.

There were many "oversights" in Waldeck Rochet's report. There was not a word, not a single word, of protest against the Gaullist repression which followed the mobilization of May 1968. There was not a word of protest against the expulsions of foreigners, not a word of protest against the dissolution of the revolutionary organizations.

Waldeck Rochet did mention, though only in passing, the murder of a young Communist in Arras by the Gaullists during the electoral campaign. However, he did not say one word about the clashes at Flins and Sochaux.