On Immortality

What does it mean to write about immortality in relation to communism, Mao Zedong Thought, and people’s experiences of life under the Chinese Communist Party?

When I graduated from university in 1966, I sincerely believed what I was taught, that I was a brand-new bolt to be used in the construction of the great mansion of communism. I was willing to be put wherever my country needed me, and I was prepared to stay in place my whole life. To me, Mao was like God. I believed that he was not only the great leader of the Chinese people, but also the great leader of people throughout the world. I feared the day when he would no longer be with us. I really hoped there’d be a scientific breakthrough that’d enable young people like us to give up voluntarily a year of our own lives, to add a minute to his. That way the world would be saved.

Dai Qing, 1995

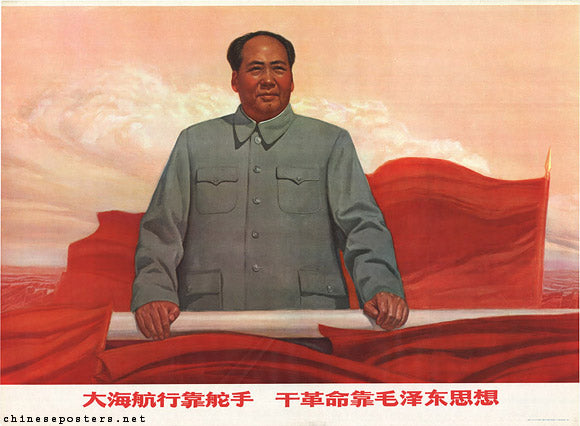

I have sometimes used these remarks in a course I teach on modern Chinese history to illustrate the extent to which young people were in thrall to Mao Zedong during the Cultural Revolution. They also appear as the first of three epigraphs in Frederick Teiwes’s essay, ‘Mao and His Followers,’ which I regularly set as required course reading. Echoing Teiwes, I tell my students that the epigraphs exemplify Mao’s stature in a totalitarian Party-state system, in which ‘virtually all members of the body politic became the Chairman’s followers, willingly or not, with varying degrees of enthusiasm.’

Reading Dai Qing’s remarks this way translates her enthusiasm for Mao’s revolutionary vision into a delusion. Dai Qing herself wanted to be read this way. She discussed her youthful wish to extend Mao’s life to highlight by contrast how, upon regaining her senses, she ‘didn’t shed a single tear when Mao died. I felt I’d been cheated. I’ve never visited the Mao mausoleum. It is so disgusting.’ Comparing Mao with Deng Xiaoping, she said:

Mao had the personality of a romantic poet. Deng’s is that of a pragmatist. He is not a puritanical theoretician or an idealist. He is different from Mao in that he knows that when people are hungry they need to eat. They can’t live on poetry.

While Dai wanted to convey the necessity of the reforms launched by Deng, her characterisation of Mao as ‘romantic,’ ‘puritanical,’ and ‘idealistic’ was not entirely negative. Moreover, there is something wistful about her comment—‘They can’t live on poetry’—as if she were wondering what might have happened if people could live on poetry.

At any rate, it is generally through poetry, including song lyrics and religious uses of poetic language in chants, mantras, and prayers, that senses of the sacred are given expression. Geoffrey Hartman provides the helpful observation that:

The sacred has so inscribed itself in [poetic] language that while it must be interpreted, it cannot be removed. One might speculate that what we call the sacred is simply what must be interpreted or reinterpreted, ‘A Presence which is not to be put by.’

What does it mean to write about ‘immortality’ in relation to communism, Mao Zedong Thought, and people’s experiences of life under Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule in Mao’s time and since? A pat answer would be that immortality is a figment of the imagination. One could always trot out the Cultural Revolution chant, ‘May Chairman Mao live ten thousand years, a hundred million years!’ (mao zhuxi wansui wanwansui), as an example of how dangerous it is to believe in immortality. Yet, to dismiss the Cultural Revolution as totalitarian brainwashing prevents us from engaging with people’s reverence for Mao productively, as a certain experience of the sacred, however disfigured.

As Dai Qing’s remarks make plain, she wanted Mao to live longer because ‘that way the world would be saved.’ The ‘immortal,’ as longevity, is bound to the ‘sacred’ as that which endures and grants meaning and purpose to otherwise mortal lives. A prosaic reading of Dai’s remarks confines us to see how Mao was exalted and worshipped. A poetic reading allows us to dwell on how people were genuinely inspired by Mao to defend communism as a sacred cause: how communism—as interpreted by Mao through Mao Zedong Thought—became a certain ‘Presence which is not to be put by.’ The frequent posthumous references to Mao and his legacy in mainland public discourse as ‘undecaying’ (buxiu) gestures to something incorruptible that remains worthy of commemoration, despite the violence and extreme suffering of the Maoist years.

Undecaying

Hartman took his figuration of the sacred from William Wordsworth’s ‘Ode on Intimations of Immortality.’ Wordsworth’s poetic formulation of ‘a Presence which is not to be put by’ alludes to the sacred as a truth that commands our attention: one we cannot escape except through childlike oblivion or wilful denial. Immortality for Wordsworth was the spiritual dimension of human existence: ‘We respect the corporeal frame of man, not merely because it is the habitation of a rational, but of an immortal soul.’ This description is akin to the Chinese idea of immortality as the ‘undecaying’ hence ageless truth that the sagely embody, in life and after their death. The difference is that whereas the Christian tradition led Wordsworth to intimate a godly presence in human nature, the Chinese idea of buxiu is directly focussed on human continuity. Both, however, point to immortality as an idea borne of existential reflection on death as intrinsic to life. The immortal, whether as ‘a Presence which is not to be put by’ or as buxiu, articulates a human preoccupation with all that precedes and succeeds us; with what is, or has turned out to be, indestructible despite mortal brevity.

The earliest extant appearance of buxiu is in the classic Confucian text Zuo Commentary (circa fourth century BCE), where the term was used to describe the sagely who are remembered for generations to come because they have ‘established their virtue, their deeds, and their words’ (li de, li gong, li yan). Simon Leys has observed that this ancient Chinese understanding of immortality meant that ‘life-after-life was not to be found in a supernature, nor could it rely upon artefacts: man only survives in man—which means, in practical terms, in the memory of posterity, through the medium of the written word.’ Immortality, in the sense of an undecaying reputation, is a matter of human judgement. The Zhuangzi, a classic Daoist text, offers the following criteria for judging who among the dead ought to be remembered:

Those who come before us but who have not explored the depths of knowledge to be worthy of their years are not our predecessors. Those who do not distinguish themselves as humans do not provide a path for [other] humans to follow. Those who do not produce a human path are thus called worthless people.

These Daoist criteria accord with the Confucian understanding of history as the ongoing textual transmission of life’s lessons and moral truths. To read Mao’s legacy against this longue durée context of instructive Confucian and Daoist stories (told and retold) of sagely and skilled humans is to be led to ask if there are things about Mao that have not ‘decayed.’ To understand immortality in these Sinophone terms requires us to consider the extent to which Mao’s textual remainders remain in some way constitutive of how mainland Chinese experience their lives and articulate their feelings and goals.

But let me first recall an influential 1919 essay by China’s leading liberal thinker Hu Shi titled ‘Immortality: My Religion’ to highlight the significance of buxiu in modern Chinese thought. To transpose premodern buxiu into a modern democratic idiom, Hu employed two concept-metaphors, ‘lesser self ’ (xiao wo) and ‘greater self ’ (da wo). He described China as an ‘immortal society,’ the permanence of an evolving ‘greater self’ to which mortal humans are bound and to which they must contribute as ‘lesser selves’ over their lifetimes:

This ‘lesser self ’ that is me [wo zhege ‘xiaowo’] has no independent existence. It has direct or indirect relations of mutual influence with an infinite number of other ‘lesser selves,’ the whole of society and the world as a totality ... . All kinds of causalities past and present, created by an infinite number of ‘lesser selves’ and an infinite number of other forces, have become a part of the ‘lesser self’ that is me. This ‘lesser self’ that is me, combined with various causalities past and present will be passed on to future generations to constitute an infinite number of future ‘lesser selves.’ From one generation to the next, an unbroken chain is formed, drop by drop, an incessant torrent results to become the ‘greater self’ ... . Although the ‘lesser self’ will die, the conduct of every ‘lesser self,’ the sum of its merits and flaws, its every word and deed, no matter great or small, true or false, good or evil, is preserved in that ‘greater self.’ That ‘greater self’ is thus the stele and the ancestral hall commemorating virtues past, the book of judgement and posthumous titles indicting crimes committed that generations of filial sons and loving descendants cannot alter. Because this ‘greater self’ is immortal, the endeavours of all ‘lesser selves’—every word and deed, gesture and idea, merit and flaw—become equally immortal. This is none other than the immortality of society, the immortality of the ‘greater self.’

Accordingly:

The ‘lesser self ’ that I am at present must shoulder an immense responsibility not only for that eternal ‘greater self’ that has always preceded me but also for that ‘greater self’ that is eternally in the future. Thus, I must always contemplate: in what ways can I best apply myself to ensure that the present ‘lesser self’ is worthy of the ‘greater self’s’ eternal past and does not bring calamity to the eternal future of the ‘greater self?’

These passages from Hu indicate the ease in modern Chinese intellectual discourse of reading buxiu as an ever-changing—hence never-decaying—world to which one belongs and helps to renew. A similar idea is implicit in Dai Qing’s self-reference as ‘a brand-new bolt to be used in the construction of the great mansion of communism’ albeit far more narrowly and rigidly articulated. Whereas Hu conceived of an ever- evolving ‘greater self,’ constituted as much by the flaws as merits of countless ‘lesser selves,’ communism for Dai Qing was synonymous with Mao, the ‘greater self’ with which all ‘lesser selves’ must form a perfect union. The popular Cultural Revolution slogan—attributed to the soldier-martyr Lei Feng—that one must desire to be ‘a revolutionary screw that never rusts,’ illustrates a similarly drastic reduction of the greater to mean the eternal machine of communist revolution that one must serve as a perfect cog. The more deterministic da wo becomes, the less room there is for variations in individual xiao wo agency. During the Cultural Revolution, we could say that the idea of buxiu shifted from a sense of ‘never-decaying’ historical change to an Orwellian ‘endless present’ in which Chairman Mao was always right.

Decaying

The feverish chanting of Cultural Revolution slogans lasted for as long as the Party- state was able to devote energy and resources to sustaining Mao’s vision of continuous revolution. A decade after Mao’s death in 1976, with post-Maoist economic reforms underway, the Beijing novelist Wang Shuo became a bestselling success with his parodies of Maoist discourse in works such as The Operators (Wanzhu, 1987), ‘An Attitude’ (Yidian zhengjing meiyou, 1989), and Don’t Treat Me as a Human Being (Qianwan bie ba wo dang ren, 1989). The farcical treatment of Maoist discourse in mainland China from the 1980s is analogous to the parodic uses of official language known as stiob which flourished in the Soviet Union from the late 1970s. Wang’s characters speak in ways that echo Alexei Yurchak’s description of stiob as requiring ‘such a degree of overidentification with the object, person, or idea at which this stiob was directed that it was often impossible to tell whether it was a form of sincere support, subtle ridicule, or a peculiar mixture of the two.’

Yurchak’s highlighting of the ambivalence in stiob is important. In China as in the Soviet Union, playful, sardonic overidentification with the language of the Party gave people a sense of social communion and solidarity in post-Maoist times, based on their prior experience of Maoist sociality. What Wang and others parodied was the discourse taught and approved by the Party that became linguistically ordered around Mao Zedong Thought in the Cultural Revolution years. This was a discourse shaped, among others, by Lin Biao (Mao’s one-time successor before Lin’s purge and death in 1971), Jiang Qing (Mao’s wife), and her fellow-members in the Central Cultural Revolution Small Group formed under Mao’s orders in 1966. Mao’s own words, conversely, have largely been spared this profane treatment. This distinction between the Party’s Maoist formulations and actual ‘quotations from Chairman Mao’ (Mao zhuxi yulu) is crucial. Because the Party’s formulations derived their authority from Mao, they were never and could never have been equal to the Chairman’s, as it were, unique authorial voice.

The Party’s foundational motto, ‘Serve the People’ (wei renmin fuwu) is an interesting case in point. Its authority derives from the title of a short speech that Mao delivered on 8 September 1944 to eulogise Zhang Side, a communist soldier who had died in an accident three days earlier while making charcoal. Much of Mao’s speech highlighted the CCP’s commitment to always ‘have the interests of the people and the sufferings of the great majority at heart’ such that ‘when we die for the people, it is a worthy death.’ Today, when protestors seek to hold the government accountable on any number of issues, they invoke this motto both seriously and as a jibe. The Beijing-based writer Yan Lianke’s darkly humorous 2005 novel Serve the People depicts a love affair during the Cultural Revolution in which the characters aroused each other by using ‘Serve the People!’ as their private code word. In doing so, Yan does not so much diminish as dramatise the affective force of the slogan as part of people’s everyday communication and interaction. Even when parodied, the motto, as Mao’s word, retains an inexorably normative rightness.

Earthly Immortality

In saying all this, I am not sacralising Mao. Rather, I want to highlight the ways in which his words have continued to enjoy a commanding presence in mainland public discourse. They are often what people reach for when they want to express their desire for a transformative politics. When student protestors at Tiananmen Square staged a hunger strike in May 1989, they issued a manifesto that began with lines from a 1919 essay by Mao: ‘This country is our country, this people our people: if we don’t speak out, who will? If we don’t take action, who will?’

When the highly regarded artist and social commentator Chen Danqing addressed a packed audience at Guangxi Normal University in 2011, he mused with stiob-like ambivalence that he ‘missed Mao very much.’ This was because people no longer knew how to be idealistic to the point where ‘because of your foolish ideal you’re even prepared to give up your life without regret and you might even laugh as you’re about to die.’ He continued:

Be truly fearless for there’s nothing to fear. That’s what Chairman Mao taught me. Don’t be afraid of heaven, earth, or capitalism ... . He taught us to fear nothing. The culture today tells us to be ever fearful, to be good and obedient.

Using Mao’s language to evoke an ideal attitude is clearly different from quoting Mao Zedong Thought. In these post-Maoist evocations that render Mao’s words serviceable for a variety of purposes, he has been restored, as it were, to ‘lesser self’ status. For this to happen, Mao had to first be adjudged as fallibly human. The Politburo’s 1981 Resolution did just that by determining Mao’s leadership as having been 70 percent correct and 30 percent wrong. Stories about Mao’s private life and habits have also become part of this ‘humanising’ process. There have been stories too of his irritation with being worshipped. For instance, at the million-strong rally of 18 August 1966, Mao reportedly replied to a Red Guard’s declared wish that ‘Chairman Mao live forever’ (zhu Mao zhuxi wanshou wujiang!) with the quip: ‘Even long life comes to an end!’

Mao, as an object of endless discussion, of stories publicly told and shared, has become demonstrably buxiu in Hu’s modern sense of a ‘lesser self’ whose words and deeds, gestures and ideas, merits and flaws contribute to the ‘greater self’s’ ongoing metamorphosis. Hannah Arendt’s defence of ‘earthly immortality’ as a necessary transcendence of ‘the life-span of mortal men’ resonates with Hu’s understanding of buxiu. In Arendt’s words:

The common world is what we enter when we are born and what we leave behind when we die. It transcends our life-span into past and future alike ... . It is what we have in common not only with those who live with us, but also with those who were here before and with those who will come after us. But such a common world can survive the coming and going of the generations only to the extent that it appears in public. It is the publicity of the public realm, which can absorb and make shine through the centuries whatever men may want to save from the natural ruin of time.

As literature, Mao’s evocations of immortality are not discordant with Arendt’s or Hu’s. He saw unceasing change as a fundamental law of human existence. Mao expressed this idea lyrically in 1949 in his heptasyllabic classical-style poem, ‘The People’s Liberation Army Has Taken Nanjing.’ The poem’s last two lines, which draw on Daoist images of cosmic mutability, read:

If Heaven had feelings, it too would grow old,

Seas thrice turned into mulberry fields: that’s the way of the human world.

In 1958, he stated more prosaically: ‘Disequilibrium is normal and absolute, whereas equilibrium is temporary and relative.’ Among the stories that have surfaced about Mao in recent years there is one concerning his 5 April 1954 visit to the Ming Tombs north-west of Beijing in the company of several ‘democratic personages’ (minzhu renshi). As his companions lamented the tombs’ state of disrepair and recommended to Mao that the tombs be restored to their former glory, Mao reportedly replied:

The desire of these emperors to be immortal [buxiu] is both laughable and tragic. They built monuments to themselves using the blood and sweat of the labouring people, which is simply despicable. A true monument is built in the accounts of history. When established in the hearts of the people, it becomes a great monument; only then can it be called immortal. We should not be wasting our efforts on restoring ruins. That they are ‘ruins’ is their historical reality. People should come here to think about history and to see historical change.

These remarks do not appear in either the collected works of Mao or the six- volume Chronological Biography of Mao Zedong: 1949–76 published in 2013. Official verification, however, is not the issue here. Rather, it is that citations of Mao are not the monopoly of the Party.

Though few would wish to return to the totalitarian conditions that enabled the cult of the Chairman, in mainland public discourse, Mao’s passion for revolutionary change is often fondly remembered. For a large majority of people who experienced the Cultural Revolution as children, adolescents, and young adults, their erstwhile intense identification with Mao’s communist vision was, and remains, a powerful formative experience. Among them are senior Party officials born in the 1940s and 1950s, including the incumbent CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping, whose time in Liangjiahe village as a rusticated youth from 1968 to 1975 is presented by the Chinese state media as both character-building and shaping his leadership style. Yet like other post-Mao leaders since Deng Xiaoping, Xi has used Mao’s sayings to defend CCP rule as necessary and enduring. Discipline and stability are what he favours when speaking in his own voice. For instance, when Xi addressed students at Peking University on the 95th anniversary of the May Fourth Movement in 2014, he said:

Living one’s life is like buttoning up one’s jacket. If the first button is not fastened correctly, the rest will never find their rightful place. The buttons of life should be fastened well from the very beginning.

These words bear no trace of Mao.