Why Trump’s Actions May Lead to Iran Occupying Iraq

Bilal Zenab Ahmed on the potentially devastating consequences of the assassination of General Soleimani by the USA

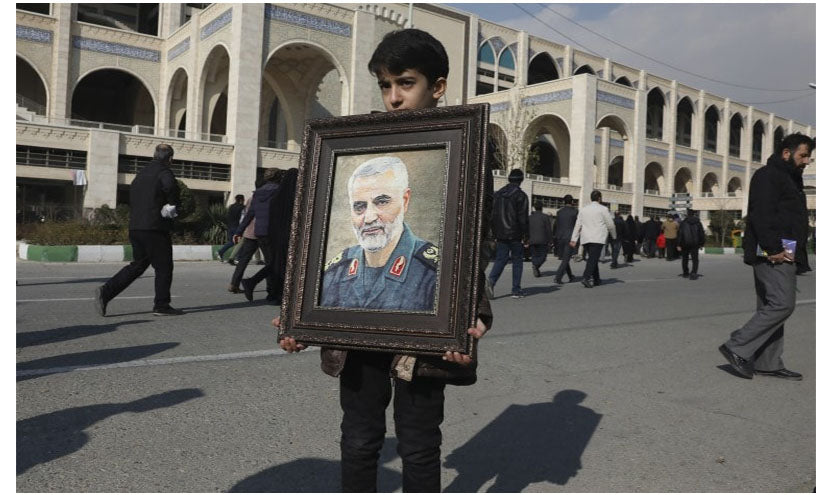

The world is still reeling from the Trump White House’s decision to assassinate Iran’s top strategic mind, General Qasem Soleimini of the Quds Force unit of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards. The drone strike that killed Soleimini at a Baghdad airport, where he was surrounded by Iraqi paramilitaries, deepened a rift that began with Trump withdrawing from the Iran nuclear deal. Last year, the standoff broke out into a series of attacks on oil tankers, in a tit-for-tat escalation that is accompanying ongoing talks.

While the situation is tense, it is unlikely to lead to full-scale war. Trump approaches foreign policy with a deal-making style, using a mixture of public threats and outright violence to flamboyantly display military might ahead of private negotiations. Trump’s aggression is largely dramatic and meant to gain leverage by terrifying skeptics and rivals - similar to Nixon’s “madman theory.” Yet in any case, Trump’s behaviour has real consequences, and Iran is likely to retaliate by deepening its hold over Iraqi state and paramilitary institutions. This would parallel the Syrian occupation of Lebanon in the 1990s and intensify processes of sectarian division and institutional fragmentation in Iraqi society.

Events are evolving so rapidly that it’s worth going over background. Last week, the US launched drone strikes against Kata’ib Hezbollah, one of many Iraqi Shi’i paramilitaries that fought Islamic State with unofficial backing from Washington. Iraq has struggled to integrate these groups and their leadership in official and semi-tribal institutions that have working relationships with Tehran. Kata’ib Hezbollah was accused of firing on US bases, and retaliated by exploiting nearby protests to help storm the US Embassy in Baghdad. It can’t be known if this decision was originally made by Tehran or if local Iraqi actors made a decision that Iran had to later accept. Trump reacted to these developments, and the killing of a private contractor, with a strike that also killed the Kata’ib Hezbollah commander Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis.

Iran’s response to the unprecedented provocation continues to evolve, and local Iraqi politicians have built on condemnations of the airstrikes with a largely symbolic vote to push American troops out of the country. This was Tehran’s logical next step, which capitalises on a nationalist backlash by encouraging Iraqi partners to place themselves at the center of dissent. While Iraqi ties to Iran have become infamous in Iraq, as expressed this year through massive protests against paramilitaries and politicians accused of coordinating too closely with Iran, Tehran is now able to argue that the US is the real issue.

It is worth noting that Shi’i Islamist parties do not all favour closer ties with Iran; nor are they all even sectarian. The Islah Party of Muqtada Al-Sadr (once a paramilitary intellectual and firebrand critic of the American occupation) leads a Shi’a-majority nationalist opposition to Tehran’s influence. Protesters in a growing national movement have been notably anti-sectarian, pushing for a diverse and inclusive society free of foreign interference. Iran tends to partner with ambitious men that have long-standing ties with its military and intelligence apparatus, and was Soleimini who mapped out many of these connections.

Tehran is likely to deepen these connections for the purpose of sidelining critics and crush the parts of the protest movement, which won symbolic gains in the October Revolution, most hostile to it. It is important to remember that Kata’ib Hezbollah was one of several paramilitaries to deploy snipers against protesters in October, reflecting Tehran’s wish for the government to survive popular demonstrations. The seizure of the US Embassy in Baghdad, which ended after one day following joint instructions from the government and the Hashd Al-Shaabi (a paramilitary umbrella group), must be understood as an action that was taken against pro-democracy protests, and in defense of the government and its ties with Tehran.

It is fair to speculate that after failing to crush mass protests through state and paramilitary crackdowns, local Iraqi actors are now seeking to hijack its energy. Their plan is to marry the October Revolution with their own objectives, by pushing against the US, and Tehran is encouraging these moves due to an overlap with its own strategic interests. This option would have been unthinkable only a month ago, but Trump’s belligerent actions have put it on the table. Presuming that the US is forced to scale back its involvement, Iran could use its freshly deepened ties with Russia to get diplomatic cover for much deeper expansionary activity. This could even mean that it mixes its own troops with paramilitary forces in order to police the country and discourage moves away from an emergent Iranian orbit (as Russia does in Ukraine).

This approach is not inevitable, but it seems likely; particularly in light of Iran’s limited military abilities, and the relative ease with which it could get involved in an Iraqi sovereign push against the US. Pundits are terrified of Iran “activating its proxies,” but what Tehran actually tends to do is encourage actors that are already in operation to continue activities that overlap with its own interests. This has already been the case with Hamas in the Gaza Strip, and the Houthis in Yemen, both of which serve as low-cost allies since they are self-sustaining groups with independent command structures. If Tehran plays its cards well, then the White House and Pentagon would be humiliated by Iraqi national backlash forcing the United States to scale back from operating freely (except for in Iraqi Kurdistan). The resulting loss in prestige and strategic flexibility would more than qualify as the “vengeance” promised by Ayatollah Khameini.

Arguably the strongest regional parallel for the Iranian push is the Syrian occupation of Lebanon, which began when Syria entered Lebanon as part of an Arab peacekeeping force in 1976. Syrian domination of Lebanese political and economic affairs far outlasted the civil war that originally framed its entry. It was only in 2005, following the assassination of Rafiq Al-Hariri and the resulting Cedar Revolution, that Syria withdrew its forces in the midst of an institutional crisis. These are obviously very different countries with their own histories, and Tehran will not simply copy Damascus’ playbook. The point is simply that Iran is well-positioned to build a lasting infrastructure for controlling Iraqi affairs, through an institutional nexus of political parties, media outlets, and paramilitaries that are willing to partner with it.

Of course, the open question is the Iraqi protest movement. While protesters have not been able to take power, as of yet, they could still shape the situation in unexpected ways if they’re able to capitalise on opportunities to confront and/or destroy hostile institutions. The situation is changing very rapidly and it would be unwise to predict its final outcome. However, if protesters aren’t able to take control, then the October Revolution and the unrest that accompanied it will become yet another regional example of a popular uprising that ends up triggering an elite power struggle with foreign involvement.