A View from Trump Country?

Appalachia has the highest concentration of white poverty in the nation. Now in 2020, years after Vance, Hochschild, and 'the Red State Revolt', Tarence Ray provides a new view from the heart of so-called "Trump Country."

Every week, our town’s newspaper, the Whitesburg, Kentucky Mountain Eagle, runs a feature known as “Speak Your Piece.” Anyone is allowed to call in and leave a message concerning basically anything, and the newspaper will print it. The “pieces” run the gamut from small town gossip, to political musings, to idle threats, police tips, religious sermons, jokes, and simple shout-outs. I’ve always thought of it as the collective id and superego of the community, both expressing its most base, unconscious desires, and issuing instructions on how to navigate the world.

I’ve therefore come to rely on it more than conventional polling when trying to gauge the political temperature of my region. The mainstream narrative about where I live—in the rural, Appalachian region of Eastern Kentucky—is that it’s “Trump Country.” This narrative assumes that the region is Trump’s natural base, and that it’s packed to the brim with Trump supporters. This is not entirely inaccurate. Most of the political signs, bumper stickers, speeches, and comments that I encounter on a daily basis are indeed conservative and pro-Trump. But “Speak Your Piece” paints a more nuanced picture. Here, because people are able to comment with anonymity, they feel a little more free to say what they want to, and a little less scared of the consequences. As a result, you’ll find that there are plenty of liberals, anti-racists, anti-fascists, and even Bernie supporters in the community. And there are of course plenty of people who are fed up with the political process altogether.

A recent “piece” provides an example. “I don’t think the people of eastern Kentucky should vote this year for the Democrats or the Republicans,” the author writes. “They promised us jobs when they took our coal away and now we don’t have anything. We are losing everything in Eastern Kentucky and it’s time we started fighting back. Do not vote.” [Italics mine]

Now, the first thing to understand about this statement is that it was published in a town where five out of six city council members forgot to file their campaigns for re-election this year. So right out the gate the commenter is making plenty of sense. The local politicians are all so inept they can’t even get their paperwork in on time to run for re-election—what hope do we have that they’ll turn this place around?

The next thing you have to realize is that Hal Rogers, the representative for Southeastern Kentucky’s Congressional District (KY-5), has been in office for forty years, and simply cannot be voted out. In fact, he is one of the most powerful men in Washington. As one of thirteen members of the elite “College of Cardinals” that effectively controls how the government spends its money, he has all but ensured he’ll never lose power over a region that has become his personal fiefdom. He has for example turned the area of Somerset, Kentucky, into a palatial “Taj Ma-Hal,” as the locals call it, creating an office compound of multiple nonprofits that vacuum up federal grant money. His designs have brought home so much federal spending, in the forms of grants, law enforcement jobs, and prison construction projects, that he’s earned himself the nickname “Prince of Pork.” He’s even named a major highway after himself, evicting none other than the illustrious American folk hero Daniel Boone from his once eponymous parkway. Eastern Kentucky is Hal Rogers’s kingdom, and you aren’t simply going to vote him out on a promise.

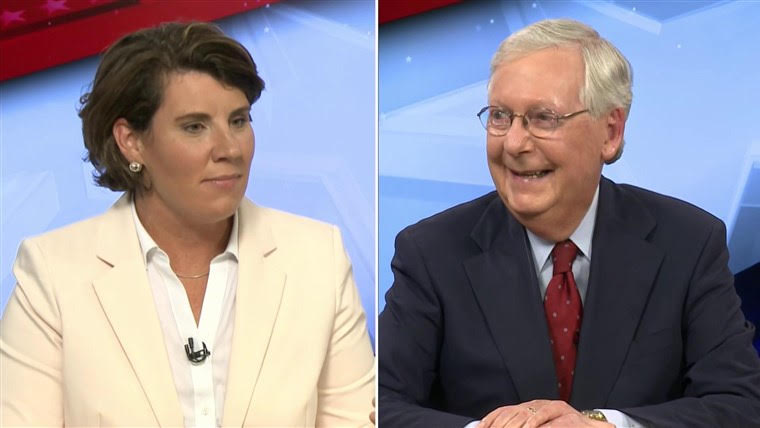

If you’re an agitated voter in Eastern Kentucky, the next election that you won’t be able to influence is the Senate race between Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and former Marine fighter pilot Amy McGrath. Earlier this year McGrath beat her primary challenger, a leftwing insurgent from inner city Louisville named Charles Booker, a member of the state’s lower chambers who ran on policies such as Medicare 4 All and a Green New Deal. Booker championed these policies under a vision he called “Hood to the Holler,” which tied together the state’s urban and rural areas under the shared fight against a common exploitation. It was inspiring, and it was dangerous, and it had to be defeated. Booker’s shoestring budget operation couldn’t compete with the millions of dollars flowing into the McGrath campaign, nor could it compete with Chuck Schumer and the DSCC’s endorsements of McGrath, and so he wound up surging too late. Our fighter pilot barely squeaked by, and now she faces McConnell, who is sure to win.

This race is particularly frustrating because McConnell is in fact vulnerable. He stopped bringing anything substantial back to Kentucky long ago. He’s not like machine-man Rogers; he doesn’t demand absolute fealty from every one of his constituents. He only requires it from the ones he needs to win his races – which means a shrinking pool of voters – and that’s what he gets. As a result, he’s become extremely unpopular in the state; many people in Eastern Kentucky despise him. But he does have one leg to stand on, and only one: he keeps Kentucky relevant at the national level, allowing it to “punch above its weight” against heavy hitters like New York and California. Again, we don’t actually get anything out of this arrangement, other than the fantasy of our issues being addressed and the projections of the “I’d-rather-be-at-brunch” liberals. But the idea does sound good on paper, and so he manages to get by.

And it doesn’t hurt that the Democrats refuse to run anyone of substance against him. McConnell’s last challenger was Alison Lundergan Grimes, daughter of a major Kentucky Democratic Party scion and thus the heiress fail-daughter to the Kentucky Democratic Party. Her own father came from a generation when Kentuckians still voted for Democrats, and not even she could beat McConnell. The McGrath campaign is twice as inept and half as charming. It’s been surreal to watch how, over the course of her campaign, her go-to inspirational story has become about the time she stood by to receive the order from President Bush to shoot down Flight 93 on 9/11. I may not be James Carville, but I believe it’s generally considered poor form to brag about your willingness to gun down your fellow Americans.

All of which is to say that the commenter from earlier may have been on to something. Throw in the presidential race—which won’t be decided by Kentucky, and which will of course be sending its whopping 8 electoral votes to Trump—and you’ve got a situation where, if you live in a town like Whitesburg, just about every political race in front of you has already been determined in some way. In such a context, the very act of not participating seems like a revolutionary act, or at least a reasonable one.

What accounts for this situation? Why do we have some areas of the country where change is so desperately needed, but is impossible to achieve? Why do we have some politicians who cannot simply be voted out?

Peeling back the history of Eastern Kentucky provides an explanation. Eastern Kentucky has always been rich in the raw materials that the country has needed to fuel industry. This meant that its politics had to be tightly controlled by coal operators and timber magnates. As the 20th century progressed, the economy changed, but the politics didn’t. In fact, because the economy changed so much and so rapidly, the political regimes had to stay static and repressive. Following trends across the former industrial and extractive heartlands of America, this region that concentrated its employment opportunities amongst men as coal miners and timber removers now employs mostly women as service workers and nurses.

These kinds of changes within the gender economy usually provide an opening for political contestation from workers and the lower/middle classes. But such a contestation could never find its footing in Eastern Kentucky, because right around that time the region experienced a massive flood of prescription pain pills and therefore excessively repressive law enforcement techniques. The result was the creation of a new Dangerous Other, a new Villain that communities had to be vigilant against. For example, in the 1990s the Kentucky State Police ran a drug enforcement program named CUPID—Criminally Undesirable People Involved in Drugs. This fascistic-sounding program became the blueprint for Hal Rogers’s own drug enforcement program, Operation UNITE, which was launched in 2003 and was the first of its kind in the nation. It encouraged residents to snitch on their neighbor’s suspected drug activities, and sent dozens of undercover agents into homes and communities.

Such law enforcement practices shattered and fragmented Eastern Kentucky’s social fabric, and the fault lines are still with us today: look no further than the fact that the deep structural changes within the region’s gender and formal economies never resulted in any kind of political contestation. There was a new crisis that people had to respond to—drug addiction—and this therefore required preserving the same good-old boy networks that had dominated the region’s institutions for so long, which then required that people shut up and accept their lot until we just get this problem under control, and on and on until all the old systems of social control were reproduced and reified on even more bleak and repressive terms.

Finally, each and every one of the people excluded from the formal economy became prey for the predatory lending practices of payday lenders. Most people are tied into many forms of debt peonage, and they can’t escape because stable, long-term employment is virtually a foregone conclusion. They can’t work the land because they don’t own the land—the land is owned by absentee coal and timber companies and, in some baffling cases, by universities like Harvard—and they can’t work a job because there are no jobs.

In aggregate, how could this lead to anything but a deep sense of powerlessness? The economy has changed so rapidly in rural America over the last few decades that it’s hard to even make sense of things. Such dramatic change will be familiar to urban areas too, but the size, dynamism and turnover of cities have made for a different kind of metabolism, more capable of absorbing and normalizing transformation. In rural areas, things aren’t supposed to change all that much. And yet, because of deindustrialization, the opioid epidemic, the proliferation of payday lenders, and changes in the gender economy, the rural areas been completely revolutionized in a relatively short period of time. But for all the dust kicked up by these evolutions underway, it never seems to rise to the level of electoral politics, whose main players never even recognize these changes in clear and honest terms. This would make even the sanest person question their commitment to the democratic process.

So back to the speaker’s comment. “They promised us jobs when they took our coal away and now we don’t have anything. We are losing everything in Eastern Kentucky and it’s time we started fighting back.” There is a sense that political developments are outside of one’s control, that the region has been forgotten or wrung completely dry or both, and that it’s no longer a part of the national community. This powerlessness is perhaps the overriding theme of the 2020 election in rural places like Eastern Kentucky.

So what if you simply lay down in the middle of the stream? What if you decided not to go along with the whole charade? The scolding liberals who demand you vote at all costs certainly won’t like it—but they haven’t done anything for you in over 70 years, so who cares what they think? What matters is that you will have fought back. What matters is that you will have regained a fragment of pride, of power, and of self-respect, no matter how small and seemingly insignificant the fragment. These are the people whose sense of justice I trust the most in times like these, and they’re the ones to whom my politics will be oriented in the years to come, no matter the outcome of this never-ending election season. Will they be yours?