A Foreigner, a Suspect, outside Kashmir

To be a Kashmiri in India is to be a stranger in your own country. Writer Majid Maqbool here writes about the experience of Kashmiris under the rule of Modi and the BJP.

On an overcast December morning in 2018, I checked in to a hotel in Agra, in the northern Indian state of Utter Pradesh. That morning I had taken an early morning train from New Delhi, and like many of the other tourists in the hotel that day, I was looking forward to seeing the Taj Mahal for the first time, it’s great dome visible in the distance from the window of my hotel room that morning, with its white marble minarets emerging from the morning fog.

On the ground floor, while waiting for our breakfast in the spacious hotel restaurant, a waiter approached to our table. A local, he wore a neatly pressed, gray hotel uniform with a metal nameplate on the breast pocket of his shirt. Earlier, we had seen him offering his younger colleagues occasional and brief directions, spreading them out across the dining hall. By the time we arrived, the restaurant was already filled with foreign tourists who had arrived overnight, each expecting to see the famous Taj Mahal and the ancient fort of Agra.

Stopping by our table, the waiter greeted us with a warm smile. It was not the kind of stock smile waiters generally use to greet guests at the doorbell of their hotel rooms. He offered us tea, pointing at the empty cups on our table.

“Are you from Kashmir?” he asked suddenly in Hindi, as he poured tea from a small flask.

I wasn’t expecting this question on the first day, even if it was a question I’d been asked many times before. In fact, it was a question I anticipate whenever I travel outside Kashmir. Often, it’s merely implied, without ever being asked, with probing, inquisitive looks. Other times I get those curious, suspicious looks reserved for outsiders.

Outside of Kashmir, I can be questioned and suspected of being a Kashmiri who detests India, and who loves Pakistan, or even simply dismissed, ignored as an ungrateful ‘Indian’ who can’t be trusted.

The mainstream media in India rarely presents Kashmir through anything other than the ‘security’ prism, framing the place in terms of its landscape, tourist arrivals, and terrorism which, they repeatedly emphasize to their viewers, can only come from Pakistan. The only other news we hear from Kashmir, often flashed as a running ticker on news channels, is simply the bare number of ‘terrorist killed’. The stories of the besieged people trying to survive, living a disrupted life amidst millions of troops, hundreds of bunkers, army camps, and military convoys are pushed to the margins, forgotten, given less importance.

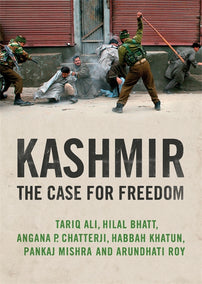

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]As a Kashmiri, I am denied agency and, in the eyes of the ordinary, proud Indians, bereft of a separate identity. I’m a foreigner living not that far away, and yet so far from belonging to a country that seeks to occupy, to obliterate my identity as if telling me every day – your land is ours and… you…you can go to hell!

The waiter was waiting for my confirmation. I said yes, I’m from Kashmir and I smiled back. He looked curious as if wanting to know more about the region. I excused myself before the curiosity grew any further to grab a glass of watermelon juice that was just then arriving at the breakfast table. The last thing I wanted that morning was to have another bitter conversation about Kashmir with those who had no idea about what it was like on the ground, who know little about the lived experiences of its inhabitants. And with those who had been there once for a few days vacation staying with their families, as they would recall, in tourist resorts like Gulmarg and Pahalgam in their childhood and teenage years. They spoke more of the picturesque landscape of Kashmir – the beautiful gardens, lakes and the overwhelming mountains – than the lives of its people caught in this endless conflict. Falling in love with a place on a short visit is easier than engaging with, and exploring, the landscape of pain of its dispossessed inhabitants.

(A man walks on a barbed wired street during a curfew imposed by the Indian government in Srinagar city area. Picture: Adil Abbas)

Surrounded by military forces and bunkers and checkpoints, the besieged people are forced into oblivion; their stories made invisible. They tend to overlook or ignore the militarization, the troops and their bunkers, camps, and convoys so clearly visible on the streets. In the past such conversations would end midway, often with the other person, a proud Indian, refusing to let go of his preconceived notions and stereotypes, unable and unwilling to understand Kashmir, and its people, with an open mind and see it with a clear eye.

I’ve always hated explaining Kashmir – or what Kashmir and Kashmiris go through – outside Kashmir. It’s like inflicting more pain on your old wounds, especially when the other person, a proud Indian, for example, has no idea of what has been done in their name in Kashmir now for decades. You’re supposed to reject acts of violence and prove your humanity while the fountainhead of violence – the state and its many forces and agencies – continues to wreck structural violence on your lives, robbing you of your idea of home, snatching your basic political and human rights.

This time, I just wanted a few quiet, uninterrupted days of vacation.

“We’ve heard a lot about Kashmir, as they also show it on news channels here,” the waiter went on as I quickly gulped down the juice. “Stones are pelted at our soldiers there…why does it happen?” the waiter asked, still maintaining a somewhat friendly tone. Yet, I could sense discomfort in his voice. For a moment, the smile on his face disappeared. He looked upset, angry. He paused between words, hesitating as if not wanting to offend while at the same time speaking his mind. He expressed his thoughts, one after another, like a monologue as I excused myself again to grab some butter for the bread.

“It’s not that people in Kashmir don’t want to be part of India…”

“Kashmir is an inseparable part of India”

“We want our soldiers to live there peacefully with the people.”

“We have also heard that Pakistan gives 500 rupees to each person to throw stones at our soldiers… Is that true?”

I was beginning to grow impatient, not wanting to clear his away doubts, correct him or argue with him. I was waiting him to have his say and leave. He didn’t. As he persisted, more than being offended from his knowledge of Kashmir, no more than expected, I was curious to know the source of his news about the region, particularly his assertion of a stone-pelting fund being pumped into Kashmir from Pakistan.

“This is what they show on our news channels here, on Zee TV and AjTak…social media videos and WhatsApp videos also show the same things,” he said, listing out his sources of information, sounding confident of the credibility of what he was told about Kashmir and Kashmiris.

[book-strip index="2" style="display"]Regional language new channels, Hindi news channels, social media posts and videos, Bollywood films, local WhatsApp groups, forwarded messages, etc – all these sources had added their own version of news which had together contributed to making opinions and informed people like him about what was happening in Kashmir.

Before heading out that morning, I left the juice half-finished on the table. The conversation too was left halfway – incomplete, inconclusive, and unresolved. Like always. The juice didn’t taste as good as it had before the talk of Kashmir with the waiter.

…

On the same day, while waiting in a long queue for entry tickets at the entrance of Taj Mahal, a security guard walked over to me.

“Sir,” he gently tapped on my shoulder, pointing to a nearby parallel queue. “Foreigner?…Wait there please.”

I was pleasantly surprised, being identified as a foreigner, but I didn’t feel the need to correct him. I smiled and stepped aside, as directed. Other people from other states queue looked on, not objecting to my separation. The elderly man immediately behind me smiled as I stepped aside and joined the queue of tourists from Iran, Indonesia and Bangladesh, all with their cameras in hand, waiting patiently for their entry tickets. He seemed happy to be a little ahead and so get his entry tickets. Perhaps the security guy mistook me for a foreigner because of my appearance. Maybe I looked like someone from Iran, as many Iranian men stood in line for their tickets in the other queue.

Some years ago, while staying in Gurgaon, in the southwest of New Delhi, I’d gone out to buy some medicine from a pharmacy. After picking the strips of tablets from the inner shelves, I walked over to the counter. The man there, after handing over the envelope after I’d paid the bill, enquired politely, “Sir, which country you’re from..?” I was surprised.

“I’m from Kashmir,” I replied with a smile after a brief pause.

“Oh sorry, you don’t look like an Indian…,” he said as we exchanged more smiles.

I wonder if I would have escaped unhurt from the same answer in the India of Narendra Modi, a country powered by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) where anything remotely anti-national, or Muslim, is unwelcome, scorned at, suspected, beaten up, and lynched. For someone from Kashmir, the twin identity – of being a Kashmiri and a Muslim – make him or her more vulnerable to mob attacks outside Kashmir.

…….

Seeing the Taj Mahal, getting close to it, was an underwhelming and exhausting, experience despite the beauty and the splendor of the monument carved out of pure love. I got a feeling that the daily visits of hundreds of foreign and domestic tourists exploring every inch of the monument had taken its toll. Inside, as the flow of tourists increased, the security staff struggled and blew whistles and shouted, trying to control the constant stream. Sometimes they’d loudly direct people with sticks, asking them to follow rules and avoid taking photos or flashing their smartphone inside the monument. Many of them did the opposite anyway.

A day later, traveling to a tourist location in the outskirts of Agra, our driver arranged by the hotel turned out to be a smart, young Muslim man from a small town in Utter Pradesh. I asked him how he is doing now that the BJP are heading the government and Yogi Adityanath is the Chief Minister.

“Since he has come to power, there is fear among Muslims here,” he said without feeling the need to add more, as he cast a brief glance at me. I didn’t insist that he explain what the fear meant. I could see it in his eyes.

Instead, I asked him about what he thinks and knows about Kashmir. He was sympathetic and better informed. He had visited Kashmir twice, he said, having once driven a group of tourists from UP in a hired tourist vehicle, and taken them to Gulmarg, Sonamarg, Pahalgam and the other tourist resorts.

“Whatever is happening in Kashmir is wrong,” he said. “Why kill innocent people. Let people have their rights and make their own decisions… There should be no force.”

…….

After a few days, at the end of the trip, we were traveling back to New Delhi in a train. As we neared the New Delhi railway station, I pulled my phone from my pocket to check social media. It was awash with photos and posts expressing grief and mourning back home. Pictures showed yet another funeral, more grieving men and women and children. Another civilian had been killed earlier in the day near yet another encounter site in Kashmir. Yet another life was cut short by a bullet.

This time the bullet fired by the government forces near an encounter site had hit a young woman, a mother, killing her on the spot. She left behind her two-year-old daughter. In the lap of her grieving father now, as some photos shared on my Facebook timeline showed, the little girl was inconsolable. She was weeping, searching for her mother… the comfort of her lap.

She will eventually get used to living without her mother. But one day, as she grows up, she’ll know who fired the bullet that killed her. And she’ll never forget – and never forgive – those who pulled the trigger. The bullet that snuffed the life out of her mother will remain, forever lodged in her memory.

She was about the age of my own daughter. She had tears in her tired eyes, rolling down her chubby cheeks. She was waiting for her mother to return and hold her in her lap and lull her to sleep. I didn’t want to read further. I couldn’t look at more of her pictures. I swiped shut my phone and looked at my daughter who was looking out of the train window, close to her mother. I brought her close, hugged her tightly, and kissed her before letting her go. She went back to her window, playfully looking out at trees and roads and houses speeding past her. She was lost in things curiously rushing past her, but not far from our sight, our protection.

Reclining on my seat, I closed my eyes. The image of that little girl waiting for her mother, not knowing where she’d suddenly disappeared, kept flashing in front of my eyes. Her almond-shaped eyes, brimming with tears, emerged from the darkness. My heart sank.

(A man rests on the bank of Dal Lake in Srinagar after the second batch of EU envoys and delegates from Gulf countries arrived in Kashmir in February 2020 to assess the ground situation in the region more than a year after the autonomous status of the region was revoked by the Indian government on August 5, 2019. Picture: Adil Abbas)

Majid Maqbool is an award winning independent journalist and writer based in Kashmir.

[book-strip index="3" style="display"]