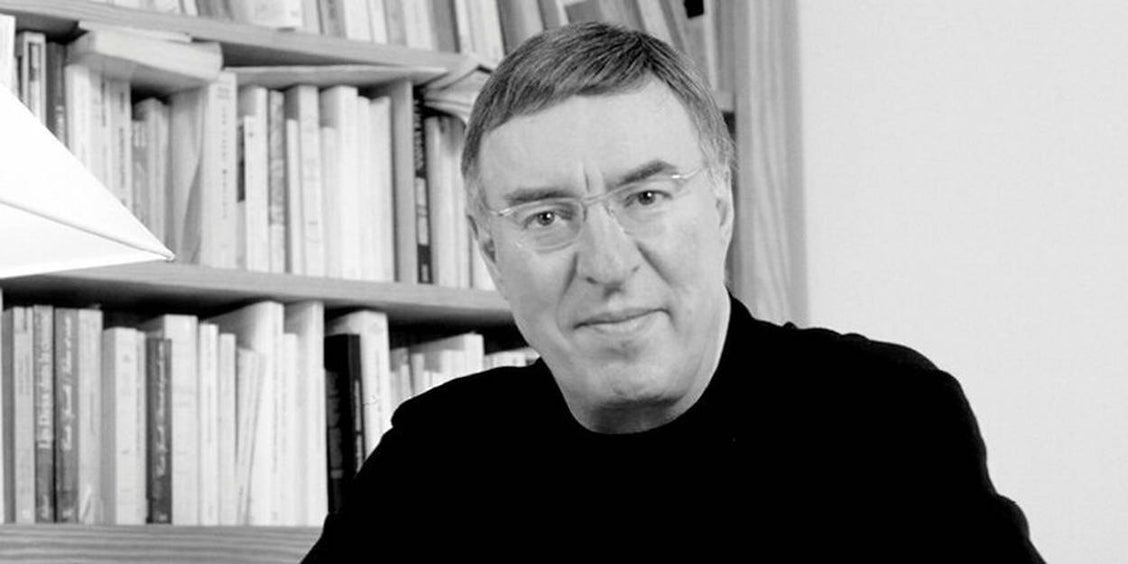

Dominique Lecourt (1944-2022)

Dominique Lecourt, author of the classics of Marxist philosophy of science Marxism and Epistemology Bachelard, Canguilhem, Foucault and Proletarian Science?, among many others, died in Paris on 1 May 2022. Here, Roger-Pol Droit remembers his life and work. Also included is a newly translated essay of Lecourt's on Foucault's The Archaeology of Knowledge.

Obituary for Dominique Lecourt by Roger-Pol Droit

Born in Paris on 5 February 1944, the philosopher Dominique Lecourt died at Lariboisière Hospital in Paris on 1 May 2022. He was the author of a copious body of work, with some forty volumes mainly centred on the relationship between philosophy and scientific or medical thought, but also a figure in publishing and cultural institutions who has left his mark on recent decades.

Lecourt studied under three major philosophers. Louis Althusser was his teacher at the École Normale Supérieure, leading him first to become involved in the Maoist struggles of the 1960s and 1970s, and later to be Louis Althusser’s legal representative after the murder of his wife in 1980. Georges Canguilhem, doctor and philosopher, supervised his dissertation on Gaston Bachelard’s L’Epistémologie historique and presented this first book, published by Vrin in 1969. Finally, François Dagognet, also a doctor and philosopher, directed his thesis, L’Ordre et les Jeux, published by Grasset in 1981.

Dominique Lecourt’s main concern, which would be expressed in different ways in the course of his work, was to analyse the relations between knowledge and present-day society, and to try to rectify these. In the wake of Bachelard and Canguilhem, he was attentive to thwarting the misunderstandings, ideological traps, and political or religious exploitation of knowledge that we see more than ever in the world today. In this spirit, he studied the creationism quarrel (L’Amérique entre la Bible et Darwin, PUF, 1992) and railed against the evils of catastrophism and technophobic apocalypse, as early as 1990 with Contre la peur (PUF), and again in 2009 with L’Age de la peur (Bayard).

Influencing the course of ideas

Another facet of this desire for action led him to develop educational tools, in particular several books in the Que sais-je? series as well as encyclopaedias and dictionaries, reissued many times in paperback, such as the Encyclopédie des sciences (Livre de poche, 1998), the Dictionnaire d’histoire et philosophie des sciences (PUF, 1999) or the Dictionnaire de la pensée médicale (PUF, 2004). He was not averse to pamphleteering either, as shown by his attack on ‘media philosophers’, who were, according to him, only Piètres Penseurs [sorry thinkers] compared to their elders (Flammarion, 1999, published in English by Verso Books as The Mediocracy: French Philosophy Since the Mid-1970s).

In a thousand ways, Dominique Lecourt sought to defend philosophy, its singularities and its capacity for action. This led him to conceive and found in 1984, with François Châtelet, Jean-Pierre Faye and Jacques Derrida, the Collège International de Philosophie, an atypical institution. This same desire then engaged him in many institutional activities, notably in distance learning, the CNRS and the Observatoire du Principe de Precaution.

His active presence in publishing is explained by this same requirement not to neglect the dissemination of ideas and to contribute to changing their course. Together with Étienne Balibar, he was director first of the ‘Pratiques théoriques’, then of the ‘Science, Histoire et Société’ collections at the Presses Universitaires de France, and chaired the supervisory board of this publishing house from 2001 to 2014.

All in all, there was a lot of Diderot in this encyclopaedist who saw himself as a friend of the contemporary Enlightenment. He did indeed devote a book to this philosopher (Diderot. Passions, sexe et raison, PUF, 2013) and chaired the Association Diderot (1984-2004), before founding the think-tank Institut Diderot, of which he was the director-general.

Given the scope of this activity as an author, publisher and organiser, we should perhaps consider the somewhat forgotten model of philosopher provided by the school of the Idéologues. Desttut de Tracy, Cabanis and Jean-Baptiste Say worked, after the French Revolution, to build the Republic by being as concerned with teaching and cultural institutions as with scientific and medical knowledge. In a sense, Dominique Lecourt was their descendant in a different world.

Translated by David Fernbach. Orignally published in Le Monde

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]Dominique Lecourt

On the Archaeology of Knowledge (about Michel Foucault)

What is the difference between a science and an ideology? This question seems to come from another age, belonging to an outdated scientism. However, the dominant ideology constantly feeds on ‘theological ideologies’, sedimented from scientific approaches or those with scientific pretensions – behavioural psychology, economics, certain readings of Darwinism, etc. In this 1970 text,[1] Dominique Lecourt reviews Michel Foucault’s book, The Archaeology of Knowledge. He takes it on as a Marxist and a disciple of Althusser. With Foucault, science and ideology are conceived dialectically. The ‘theoretical discourses’ (those with a claim to truth) of a given period impose rules and regularities on scientific production, delimiting objects of research and problems to be solved. A Marxist appropriation of Foucault is therefore possible, on condition that we identify the philosopher’s limit: his inability to articulate his history of discourse with the rest of society, with economic, political, legal and moral ideologies.

Much has been written about Words and Things. Foucault’s latest book, The Archaeology of Knowledge,[2] has aroused far less zeal among critics.

This discretion is undoubtedly due to the strangeness of a work that is likely to leave its reader with an uneasy feeling. Some will turn the last page in dismay, with the secret feeling of having been tricked. ‘It’s always the same old story, despite the verbal innovations,’ they will say, and ‘Was it really necessary to write a whole book for a change in vocabulary?’ This is a legitimate reaction, because at first reading, if the profusion of new words imposes itself on the attention and is somewhat disorienting, we quickly find ourselves at home – or rather, at Foucault’s – in the tireless attacks, repeated here a hundred times, against the ‘subject’ and its doubles. Others, once they have finished reading, will suspend their judgement and wait for the rest: ‘Everything is new,’ they will say, ‘we no longer recognise ourselves in it. But the game isn’t over: let’s wait to see how this battery of new concepts works, and then we’ll decide.’ They will not be wrong either, since the author warns us more than once that the elaboration of the new categories endangers the old edifice, that profound rectifications must be made: the category of ‘experience’ as it functioned in Madness and Civilization is invalidated because of the surreptitious restoration of an ‘anonymous and general subject of History’ (pp. 27, 74); the key notion of ‘medical gaze’ around which The Birth of the Clinic revolved is itself repudiated. By limiting ourselves to the most apparent, therefore, even to the explicit, we cannot fail to suspect a real novelty of concepts beneath the renewed luxuriance of style, even if we have some difficulty in supporting this suspicion since new analyses do not appear and the old ones are only allusively invoked.

These two contradictory reactions clearly raise the same question: why this book? What was the need to write it? It is from this question, it seems to me, that we must start. Michel Foucault, in fact, does not leave us without an answer. According to him, this book is presented as a methodical and controlled resumption of what had previously been done ‘blindly’. In fact, the references, as we have just seen, do not go beyond the circle of his previous works. Moreover, the book is full of methodological norms, and whole chapters are presented as an attempt to codify certain rules that were, we may believe, tacitly accepted and chaotically practised in the past.

It seems to us, however, that this answer, stubbornly suggested by the author, is not sufficient: the Archaeology has a different scope and the problematic it sets up is of a real and radical novelty. We will take as an indication of this novelty a very remarkable absence: that of the notion of episteme, the cornerstone of his previous work, and the fulcrum of all ‘structuralist’ interpretations of Foucault. It will no doubt be agreed that such an absence cannot be accidental. We therefore propose to take seriously the paradox of a book that claims to be a methodical ‘reworking’ of previous works and that ‘lets slip’ their cornerstone. This paradox makes the whole enterprise interesting. It raises two questions: what is the meaning of this insistence on underlining a continuity that is clearly not seamless? What novelty is being introduced that forces us to abandon the central notion of episteme?

[book-strip index="2" style="buy"]To these two questions, I think we can give a single answer: it is the abandonment that accounts for the insistence. Let me explain: Foucault felt the need to leave behind an essential category of his philosophy, but this abandonment should not be understood as a rallying to the camp of his enemies; rather, the category of episteme had profound polemical effects against any ‘humanist’ or ‘anthropologist’ theory of knowledge and history. He is keen to preserve these. However, the notion of episteme, which described ‘configurations of knowledge’ as great layers obeying specific structural laws, prevented the history of ideological formations from being thought of as anything other than abrupt ‘mutations’, enigmatic ‘ruptures’, and sudden ‘rifts’. It is from this type of history – for reasons that we shall have to examine in detail – that Foucault now wants to break away. The Archaeology records this divorce. We have already sensed it: it is the ‘structuralist’ aspects of episteme that Foucault wants to get rid of here, without putting back on the old skins of humanism that he has always fought against. The operation is perilous and did indeed require a volume; its complexity easily explains the readers’ unease and gives meaning to the critics’ discretion: in Archaeology, they no longer find their Foucault, wise prospector of epistemic structures. Even worse: they see History appearing; not their history, but a strange history that rejects both the continuity of the subject and the structural discontinuity of ‘ruptures’!

We think, for our part, that the critics are wise. They are not wrong to tremble, for the concept of history that functions in Archaeology has much in common with another concept of history they have good reason to hate: the scientific concept of history, such as it figures in historical materialism. The concept of a history that also presents itself as a process without a subject, structured by a system of laws. A concept which, as such, is also radically anti-anthropological, anti-humanist and anti-structuralist.

The Archaeology of Knowledge represents, in our opinion, a decisive turning point in Foucault’s work; we would like to show that his new position in philosophy has led him, starting with this work, to carry out a certain number of analyses of astonishing richness from the point of view of historical materialism; that, in his own language, he reproduces – but in a displaced form – concepts that function in the Marxist science of history; finally, that the difficulties he encounters, like the relative failure to which he leads, can only find a solution and a way out in the field of historical materialism.

From archaeology to knowledge

Against the ‘subject’

It can be said that the whole ‘critical’ part of The Archaeology of Knowledge is a continuation of Foucault’s previous work. If he no longer has the same allies, he still has the same adversaries. But the polemics here are enriched and deepened and bring to light conceptual solidarities that had formerly remained hidden. Thus, the attacks on the category of subject are now coupled with attacks on continuism in history.

Here is what he says to his neo-Hegelian humanist critics about Words and Things: ‘What is being bewailed with such vehemence is not the disappearance of history, but the eclipse of that form of history that was secretly, but entirely related to the synthetic activity of the subject (p. 14).’ This is the perfect alibi for anthropologism: how better to fight history than by raising its flag?

Example: Archaeology is the site of a dense polemic against a discipline currently in vogue: ‘the history of ideas’. Foucault shows that this is based on an anthropological postulate that forces it to be openly or shamefully continuistic. The ‘history of ideas’, according to him, has two roles. On the one hand, it ‘recounts the by-ways and margins of history. Not the history of the sciences, but that of imperfect, ill-based knowledge, which could never in the whole of its long, persistent life attain the form of scientificity (p. 136).’ Examples follow: alchemy, phrenology, atomistic theories. In short, ‘It is the discipline of fluctuating languages (langages), of shapeless works, of unrelated themes.’ But on the other hand, it takes on the task of crossing existing disciplines, processing and reinterpreting them. It describes the diffusion of scientific knowledge from science to philosophy, to literature itself. In this sense its postulates are: ‘genesis, continuity, totalization. (p. 138). Genesis: All ‘regions’ of knowledge are related, as if their origin, to the unity of an individual or collective subject. Continuity: this unity of origin has as a necessary correlate the continuity of development. Totalization: unity of origin has as a necessary correlate the homogeneity of parts. Everything fits together, but cannot, according to Foucault, give rise to a true history.

New front of attack: any theory of reflection, insofar as it sees in ‘discourse’ ‘the surface of the symbolic projection of events or processes that are situated elsewhere’, insofar as it seeks to ‘rediscover a causal sequence that might be described point by point, and which would make it possible to relate a discovery and an event, or a concept and a social structure’, any theory of ‘reflection’, in its ‘empiricist’ or ‘sensualist’ background, must give itself as a ‘fixed point’ a category of subject and is therefore immediately suspect of anthropologism (p. 164). Even more surprisingly, the category of author, although ‘concrete’ and obvious, is itself rejected. The author is only ever the literary, philosophical or scientific qualification of a ‘subject’ held to be ‘creator’. As a result, the ‘book’ is a naively and arbitrarily divided unit imposed on us in an unreflective manner by the appearances of geometry, the rules of printing and a suspicious literary tradition. The ‘book’ must therefore be considered not as the literal and more or less rationalized projection of a subject that carries and establishes its meaning, but as a ‘node within a network’ (p. 23). Its real existence – not its immediate appearance – is only due to ‘the network of references’ that take shape in it. ‘And this network of references is not the same in the case of a mathematical treatise, a textual commentary, a historical narrative, and an episode in a novel cycle’.

Against the ‘object’

Let us beware: here appears, by way of an example, the most novel aspect of The Archaeology of Knowledge: the old polemic entirely turned against the ‘subject’ takes a new turn by aiming at the correlative category of object.

This is the meaning of the critical rectifications – repeated several times – against certain themes of Bachelardian epistemology. Everything is concentrated around the notions of epistemological ‘rupture’, ‘obstacle’, ‘act’. Foucault discovers the solidarity between the philosophical category of ‘object’ and the descriptive point of view of ‘rupture’ in history: it is because one compares a science with an ideology from the point of view of their objects that one observes a rupture (or break) between them, but this point of view is narrowly descriptive and explains nothing. Worse: as one can see, the category of object carries with it its correlate: the subject. Bachelardian epistemology is another good example: the notion of epistemological rupture requires us to think of what we are breaking with as an epistemological ‘obstacle’. But how does Bachelard propose to conceive obstacles? As interventions of images in scientific practice. Foucault can therefore affirm that the object-break couple is only the inverted figure, but identical in substance, of the subject-continuity couple; Bachelard’s epistemology is therefore a shameful anthropology. The ‘psychoanalysis of objective knowledge’ marks the limits of this epistemology, its point of inconsequence; the point where other principles are required to account for what it describes. Certainly – it is Bachelard’s great merit to have understood this – a science can only be established by breaking away from a ‘tissue of tenacious errors’ that precede it and hinder it, but to refer to the ‘libido’ of the scientist to account for the formation of this fabric is still to lean on a notion of the ‘subject’; it is even, ultimately, to imply that scientificity could be established by the voluntary decision of the scientist (or scientists). For Foucault, we must start from what Bachelard described, leave the point of view of the object, and pose the problem of ‘rupture’ on new bases. To be precise, we must examine the fabric that Bachelard failed to ‘think’, in particular, those ‘false sciences’ that precede science, those ‘positivities’ that the sciences, once constituted, allow us to determine by recurrence as ‘ideological’. On this point, as we shall see, The Archaeology of Knowledge provides us with much.

The instance of knowledge

Institutional materiality

We now know to what requirements the fundamental categories of Archaeology respond: it is a question of thinking about the laws that govern the differential history of sciences and non-sciences without reference to either a ‘subject’ or an ‘object’, outside the false alternative of ‘continuity-discontinuity’.

The first notion that meets these requirements is that of ‘discursive event’. Foucault writes:

Once these immediate forms of continuity are suspended, an entire field is set free. A vast field, but one that can be defined nonetheless: this field is made up of the totality of all effective statements (whether spoken or written), in their dispersion as events and in the occurrence that is proper to them. Before approaching, with any degree of certainty, a science, or novels, or political speeches, or the oeuvre of an author, or even a single book, the material with which one is dealing is, in its raw, neutral state, a population of events in the space of discourse in general (pp. 26-7).

Here, the questions pile up: what is this ‘space of discourse?’ Is it not the object of linguistics? No, because the ‘field of discursive events … is a grouping that is always finite and limited at any moment to the linguistic sequences that have been formulated’. Is it not simply ‘thought’ that is designated by these esoteric words? No, because it is not a question of referring what is said to an intention, to a silent discourse that would order it from within; the question is simply: ‘what is this singular existence that comes to light in what is said and nowhere else?’ Let us continue to follow Foucault in order to discover the specificity of this category that he constructs and to which we will later allow ourselves to give another name. It is, in fact, through the advantages he expects from it that Foucault specifies the status of what he calls ‘discursive event’. This notion makes it possible to determine the relations of statements to each other, ‘even if the statements do not have the same author… relations between statements and groups of statements and events of a quite different kind (technical, economic, social, political) (p. 29)’.

We can see that the essential thing here is the notion of relationship. What Foucault understands by relationship is a set of relations of ‘their coexistence, their succession, their mutual functioning, their reciprocal determination, and their independent or correlative transformation’ (cf. especially p. 29). But Foucault feels that the determination of such relations is still insufficient to designate the instance of ‘discursive events’. If, through such a combinatorial system, we can hope, in a sense, to account for the ‘discursive’, we would still be unable to understand what he calls a discursive event, we would remain at the level of the episteme. To put it in a nutshell: such an analysis cannot account for the ‘material’ and ‘historical’ existence of the discursive event. A key question haunts all these pages, which could seem long and redundant: the necessity recognized by Foucault to define ‘the regime of materiality’ of what he calls discourse, the correlative necessity to elaborate a new – materialist – category of ‘discourse’ and finally to conceive the history of this ‘discourse’ in its materiality. This is the threefold task that Archaeology tries to fulfil; it is also, as we shall see, what accounts for its relative failure.

The proof: referring to the ‘objects’ of psychopathology, he asks questions such as: ‘Is it possible to discover according to which non-deductive system these objects could be juxtaposed and placed in succession to form the fragmented field – showing at certain points great gaps, at others a plethora of information – of psychopathology? What has ruled their existence as objects of discourse?’ (p. 41). Even more clearly, the attempt to characterize the elementary unity of the discursive event – the unit-event, so to speak – leads Foucault to propose the notion of ‘statement’. But what does he recognize as the condition of the statement? ‘For a sequence of linguistic elements to be regarded and analysed as a statement … it must have a material existence’ (p. 100). Materiality is not just one condition among others, it is constitutive: ‘it is not simply a principle of variation, a modification of the criteria of recognition, or a determination of linguistic sub-groups. It is constitutive of the statement itself: a statement must have a substance, a support, a place, and a date (p. 101).

Without anticipating too much, we can say that the search for the ‘rule of materiality’ of the statement will orient more towards substance and medium than towards place and date: ‘the rule of materiality that statements necessarily obey is therefore of the order of the institution rather than of the spatio-temporal location’ (p. 103). What Foucault discovers is in fact that ‘spatio-temporal localization’ can be deduced from ‘relations’, or ‘relationships’ between statements or groups of statements, when we understand that we must recognize that these relations have a material existence, when we grasp that these relations do not exist outside of certain material supports where they are embodied, produced and re-produced. At the point we have reached, the situation could be summarized as follows: the need arises to conceive the history of discursive events as structured by material relations embodied in institutions.

Discourse as ‘practice’

It is understandable that Foucault should be led to give a singular definition of ‘discourse’: ‘It would be quite wrong to see discourse as a place where previously established objects are laid one after another like words on a page’ (pp. 42-3). In fact, if what we have said about the ‘material rule of the statement’ is correct, discourse cannot be defined outside of the relations that we have seen to be its constituents; this is why Foucault speaks of ‘discursive relations’ or ‘discursive regularities’ rather than ‘discourse’. This is ultimately because this discourse is a practice. The category of ‘discursive practice’ as proposed here by Foucault is the index of this theoretical innovation, in its materialist background, which consists in not allowing any ‘discourse’ outside the system of material relations that structure and constitute it. This new category establishes a decisive dividing line between The Archaeology of Knowledge and Words and Things. But it is important to understand this: the word ‘practice’ is not designed to mean the activity of a subject, rather the objective and material existence of certain rules to which the subject is subjected as soon as it takes part in ‘discourse’. The effects of this subjection of the subject are analysed under the heading: ‘positions of the subject’; we shall return to this. For the moment, here is the positive definition of discourse according to Archaeology: discursive relations are not internal to discourse, they are not the links that exist between concepts or words, sentences or propositions; but neither are they external to it, they are not external ‘circumstances’ that would constrain discourse; on the contrary, ‘they determine the group of relations that discourse must establish in order to speak of this or that object, in order to deal with them, name them, analyse them, classify them, explain them, etc.’ And Foucault concludes: ‘these relations characterize not the language (langue) used by discourse, nor the circumstances in which it is deployed, but discourse itself as a practice’ (p. 46). Hence, the notion of discursive rule or regularity to designate the norms of this practice. Hence, the definition, to which we have already alluded, of the ‘objects’ of this practice as ‘effects’ of the rules, or the ‘group of relations’: it is indeed necessary ‘to define objects without reference to the ground, the foundation of things, but by relating them to the body of rules that enable them to form as objects of a discourse and thus constitute their conditions of their historical appearance’ (pp. 46-7).

The instance of knowledge

This is how the notion of ‘knowledge’, the proper object of archaeology, is constructed. What is a knowledge? It is precisely ‘that of which one can speak in a discursive practice, and which is specified by that fact: the domain constituted by the different objects that will or will not acquire a scientific status’ (p. 182). ‘Knowledge is also the field of coordination and subordination of statements in which concepts appear, and are defined, applied and transformed’ (pp. 182-3). This is why, unlike epistemology, ‘archaeology explores the discursive practice/knowledge (savoir)/science axis’ (p. 183). The status of the notion of epistemological rupture is revised here. According to Foucault, epistemology’s proper function is to elide the instance of ‘knowledge’, the instance of those regulated relations whose material existence constitutes the basis on which scientific knowledge is established. For him, what needs to be shown is ‘how a science is inscribed and functions in the element of knowledge’. There would be a ‘space’ where, by an internal play, the relations that constitute it a given science would form its object. ‘Science, without being identified with knowledge, but without either effacing or excluding it, is localized in it, structures certain of its objects, systematizes certain of its enunciations, formalizes certain of its concepts and strategies’ (p. 185).

We will have the opportunity to come back to this ‘game’ as Foucault conceives it; in particular with regard to a precise example, that of the relationship between Marx and Ricardo. It is enough to have shown the principles of analysis, and their effects on the existing ‘disciplines’.

The vanishing point of archaeology

We can now consider the principle of Foucault’s approach: it seems to me that it very rightly marks the limits of epistemology, and demonstrates the need to elaborate a theory of what he calls ‘discursive relations’; a theory of the laws of any ‘discursive formation’. But it is here that the limits of ‘archaeology’ appear in turn. If our interpretation is correct, the task of ‘archaeology’ would indeed be to constitute the theory of the ‘discursive’ instance insofar as it is structured by relations invested in historically determined institutions and regulations. This task is only fulfilled by Foucault in the form of description; it is himself who says so: ‘the time has not yet come for theory’, he writes in the chapter entitled ‘the description of statements’. We think, for our part, that it has come, a long time ago; but that it will not come for Foucault if he does not resign himself to recognizing the principles of this theory that he is calling for. These principles are those of the science of history. For, in the end, the most positive aspect of The Archaeology of Knowledge is the attempt to establish, under the heading of ‘discursive formation’, a materialist and historical theory of ideological relations and the formation of ideological objects. But, in the final analysis, on what is this theory based? On a tacitly accepted, always present but never theorized distinction between ‘discursive practices’ and ‘non-discursive practices’. All his analyses come up against this distinction; we would say that it is practised blindly; and that the last effort of ‘mastery’ that remains to be made is to theorize it. We have no doubt, as he himself foresees, that Foucault will then find himself on a different terrain.

[book-strip index="3" style="display"]This distinction is always present: Foucault, having produced the category of ‘discursive practice’, must recognise that this ‘practice’ is not autonomous; that the transformation and change of the relations that constitute it do not take place through the play of a pure combinatory but that, in order to understand them, we must refer to other practices of a different kind. We have already seen that, from the very beginning, Foucault proposes to determine the relations between statements, but also ‘between statements and groups of statements and events of a quite different kind (technical, economic, social, political)’ (p. 29). Moreover, to follow the order of the book, a strange distinction appears in the definition of discourse as practice. ‘Discursive’ relations are said to be secondary, compared to certain so-called ‘primary’ relations which, ‘independently of all discourse or all object of discourse, may be described between institutions, techniques, social forms, etc.’ (p. 45). A few pages further on, we read: ‘The determination of the theoretical choices that were actually made is also dependent on another authority. This authority is characterized first by the function that the discourse under study must carry out in a field of non-discursive practices’ (pp. 67-8).

We could cite many other examples that would all prove that Michel Foucault needs this distinction but that he practises it in the form of juxtaposition. We will see, in particular, how this is at work in his analysis of the relationship between Ricardo and Marx. This is the point where Michel Foucault’s ‘system of references’ reveals its inconsistency. Let’s change the terrain.

The third section of the chapter ‘Science and Knowledge’ is entitled ‘Knowledge (savoir) and ideology’. The confrontation of the two headings indicates what this is about: a critical examination of the theses proposed by Althusser, already a good while ago, on the relationship between science and ideology. These theses, which no one can deny had, in their time, a revolutionary theoretical value and political scope, used for their own purposes a notion of ‘break’ or ‘rupture’ that was essentially Bachelardian. We have seen that Foucault proposes in Archaeology a system of categories to rethink and – rectify – this conception of the break (or rupture). He underlines its narrow descriptive value and its anthropological connotations. It is therefore understandable that, as a result, the science-ideology distinction should need reworking; which is what he undertakes to do by analysing the relationship between science and ‘knowledge’ as he has elaborated this concept in the course of the work. He thus finds himself obliged to conceive the difference between what he calls ‘knowledge’ and what Althusser called ‘ideology’. It is precisely on this last analysis that Archaeology closes. Foucault makes use of three arguments, correlative to the determinations of the new concept of ‘knowledge’:

- If knowledge is constituted by a set of practices, discursive and non-discursive, then the definition of ideology, as it functioned in Althusser, is too narrow.

‘Theoretical contradictions,’ writes Foucault, ‘lacunae, defects may indicate the ideological functioning of a science (or of a discourse with scientific pretensions); they may enable us to determine at what point in the structure this functioning takes effect. But the analysis of this functioning must be made at the level of the positivity and of the relations between the rules of formation and the structures of scientificity’ (p. 186).

In short, what is targeted is any conception of ideology as pure and simple non-science. For Foucault, such a definition of ideology misses its mark; if you like, it is itself ideological. It merely notes in a mechanistic and ultimately anti-dialectical way the effects of the insertion of science into knowledge. But the analysis must be shifted; we must not rest content, with our eyes fixed on science, with making ideology the simple obverse side of science, its pure failure, as some of Althusser’s one-sided statements have led us to believe. On the contrary, in order to grasp what is called the ‘rupture’, it is necessary to analyse the network of relations of which ‘knowledge’ is constituted, and on the basis of which science appears.

b) If knowledge is invested in certain practices, discursive and non-discursive, the appearance of a science does not magically put an end to these practices. On the contrary, they remain, and coexist with science -- more or less peacefully. Therefore: ‘Ideology is not exclusive of scientificity... By correcting itself, by rectifying its errors, by clarifying its formulations, discourse does not necessarily undo its relations with ideology. The role of ideology does not diminish as rigour increases and error is dissipated’ (ibid.). In other words, if what is meant by the word ‘ideology’ is in truth ‘knowledge’; it must be recognized that its reality, the materiality of its existence in a given social formation, is such that it cannot dissipate overnight like an illusion; on the contrary, it continues to function and to literally besiege science throughout the endless process of its constitution.

c) The history of a science can only be conceived in its relation to the history of ‘knowledge’, i.e. to the history of the practices, discursive and non-discursive, in which it consists; the question is to conceive the mutations of these practices: each mutation will have the effect of modifying the form of insertion of scientificity in knowledge, of establishing a new type of science/knowledge relationship.

This is why the question of ideology posed to science is not a question of the situations or practices that it reflects in a more or less conscious way; nor is it the question of its possible use or misuse; it is the question of its existence as a discursive practice and of its functioning among other practices.

It seems to me that this unacknowledged ‘system of references’ is now apparent, despite being masked by the author’s constant, and here paradoxical, self-reference to his work. We were right to suspect this singular ‘trick’ that Foucault plays on both himself and on us: to give as constitutive of his work a system of references whose elements he himself invalidates. What, in fact, is evident at the end of these analyses (at the end, as we have noted), is that the system of Archaeology is entirely constructed to compensate for the inadequacy of the science-ideology couple when it comes to conceiving those ‘false sciences’, those ‘positivities’, that are Foucault’s specific object. The Archaeology of Knowledge is built on the observation of a failure. Now Foucault had only two options: to try to solve the difficulty by his own means, or to trust historical materialism, the science of history, and see whether the opposition between science and ideology could be reduced to the one that – provisionally, and necessarily so – Althusser had stated earlier. To be precise: whether the fundamental concepts of historical materialism did not allow for the development of a theory of ideology such that the difficulty encountered was already resolved. Michel Foucault chose – some would say courageously – the first path. In the end, we will try to give a non-psychological reason for this choice. For the moment, we must see the consequences. To put our cards on the table and anticipate our results a little, let us say that the nature of ideology is such that it is not possible with impunity to hold a continuously parallel discourse with respect to a constituted and living science. There comes a moment when the contradiction re-forms, when the ‘displacement’ is felt through its effects, when the choice, at first evaded, imposes itself again, more urgently. This is what we shall show.

Parallel discourse: Foucault, having recognised a real difficulty, the terms and solution of which belong rightfully and in fact to historical materialism, proposes a certain number of homologous, albeit displaced, concepts. For those who know how to hear them, he sets out in their formulation the conditions of their own rectification.

As we have just seen, everything hinges on the use of the concept of ‘practice’. In its literalness, it admits that it is at this point that the distance between historical materialism and ‘archaeology’ is minimal; examination will prove, without paradox, that it is also at this point that it is maximal. It is indeed the category of practice – so foreign to Foucault’s previous works – that defines the field of ‘archaeology’: neither language nor thought, as we have seen, but what he calls the ‘preconceptual’ (p. 60), ‘The “pre-conceptual level” that we have uncovered,’ he writes, ‘refers neither to a horizon of ideality nor to an empirical genesis of abstractions.’ Indeed, he is not looking for the ideal structures of the concept, but the ‘place of emergence of concepts’; nor is he trying to account for ideal structures through the series of empirical operations that would have given rise to them; what he is describing is a set of historically determined anonymous rules that are imposed on every speaking subject, rules that are not universally valid, but that always have a specified domain of validity. The major determinant of the category of ‘practice’ in the Archaeology is ‘rule’ or ‘regularity’. It is regularity that structures discursive practice, it is the rule that orders all discursive ‘formation’ (p. 46). The function of the ‘rule’ can be easily assigned: through it, Foucault tries to conceive at the same time – I mean in their unity – the relations that structure the discursive practice, their subjecting effect on the speaking ‘subjects’ and what he enigmatically calls the ‘clutch’[3] of one type of practice on another.

We have already analysed the first point; it will suffice to add the clarification that ‘regularity’ is not opposed to ‘irregularity’; if regularity is indeed the essential determination of practice, the opposition regular/irregular is not relevant. We cannot, for example, say that, in a discursive formation, an ‘invention’ or a ‘discovery’ escapes regularity: ‘A discovery is no less regular, from the enunciative point of view, than the text that repeats and diffuses it; regularity is no less operant, no less effective and active, in a banal as in a unique formation’ (p. 145). Irregularity is thus an appearance exploited by those historians with ‘strokes of genius’ who, as good worshippers of the ‘subject’ (at least of some brilliant subjects) are, as we have seen, fundamentally continuist. This appearance occurs when a modification takes place at a given point of the discursive formation, thus in and under the regularity established at this given moment of history. Depending on the point at which it occurs, it will be more or less noticeable, it will have greater or lesser effect (some would say: it will be more or less ‘brilliant’). Thus a new determination of ‘discursive formation’ appears: it is structured hierarchically. There are indeed ‘corrective statements’ that delimit the field of possible objects and draw a dividing line between the ‘visible’ and the ‘invisible’, the ‘thinkable’ and the ‘unthinkable’, or to put it better (in ‘archaeological’ terms): between the enunciable and the non-enunciable; that designate what a given discursive formation includes by what it excludes. The appearance of irregularity is thus only an effect of the modification of the ‘rectorate’. The remarkable pages (pp. 147-8) devoted to the example of natural history would need detailed comment.

Second point: this hierarchical regularity is imposed on every ‘subject’. Here is what Foucault writes about clinical medicine: ‘The positions of the subject are also defined by the situation that it is possible for him to occupy in relation to the various domains or groups of objects: according to a certain grid of explicit or implicit interrogations, he is the questioning subject and, according to a certain programme of information, he is the listening subject, and, according to a table of characteristic features, he is the seeing subject, and, according to a descriptive type, the observing subject’ (p. 52). And, further on: ‘the various situations that the subject of medical discourse may occupy were redefined at the beginning of the nineteenth century with the organization of a quite different perceptual field (ibid.)’.

The third point is crucial; it is here that all the contradictions of the ‘archaeological’ enterprise accumulate; it is here that the Foucauldian category of practice reveals its inadequacy: it does not allow us to conceive the unity of what it designates as anything other than juxtaposition. We shall show that this is because it lacks a principle of determination. Now, if what we have said is correct, this absence is simply the effect of the path chosen by Foucault. It therefore marks the point where the other path makes its necessity felt, where the rectification can begin.

Foucault was obliged to think about what constitutes the regularity of the rule, what orders its hierarchical structure, what produces its mutations, what confers its imperative character on any subject. But on each of these points, he comes up against the same difficulty. That it is the same difficulty is not without interest: it means that Foucault conceives the necessity of referring the whole of this complex process to the same principle. But this same principle, if it is everywhere present and designated, is never conceived. This is because it exceeds the limits of the category of practice as it functions here. We have already discovered this principle: it is the articulation of discursive practices on non-discursive practices.

We will be told: all this to get to this point, that is to say, to the same enigmatic point where the previous chapter stumbled! Certainly, and this is quite natural since, past this point, we are outside of Foucault. But let us beware: we have progressed in our apparent circle; we have already determined the means of escaping the ‘archaeological’ circle. By conceiving the vanishing point as such, we have found the only way out with no loophole. In fact, we can now say what the discursive practice/non-discursive distinction responds to: an attempt to re-conceive the science/ideology distinction. Better still: an attempt to conceive in their differential unity two histories: that of the sciences and that of ideology(s). No longer unilaterally emphasizing the autonomy of the history of science, but marking at the same time the relativity of this autonomy. Now, engaged on this path, Foucault has to recognize (and this is his highest merit) that ideology (conceived under the category of ‘knowledge’ as a system of hierarchically structured relations, and invested in practices) is not in its turn autonomous. Its autonomy is still only relative. But he is well aware of the danger that threatens him; to conceive of ‘knowledge’ as a pure and simple effect – or ‘reflection’ – of a social structure. In short, from having wanted to escape from transcendental idealism, falling into an empiricist mechanism which is only the inverted form of the former. Hence his extreme embarrassment, and the vague metaphorical categories he proposes.

Let’s take these developments for what they are: the ‘recognition’, necessarily based on a misunderstanding, of a theoretical flaw in the ‘archaeological’ edifice. First recognition: the role of institutions in the ‘clutch’. Taking up analyses from The Birth of the Clinic, Foucault writes two remarkable pages on this subject (pp. 49-50); I simply quote passages from them, underlining certain words that illustrate the analysis I have just proposed:

First question: who is speaking? Who, among the totality of speaking individuals, is accorded the right to use this sort of language (langage)? Who is qualified to do so? Who derives from it his own special quality, his prestige, and from whom, in return, does he receive if not its assurance, at least the presumption that what he says is true? What is the status of the individuals who – alone – have the right, sanctioned by law or tradition, juridically defined or spontaneously accepted, to proffer such a discourse? The status of doctor includes criteria of competence and knowledge; institutions, systems, pedagogic norms; legal conditions that give the right – though not without laying down certain limitations -- to practise and to extend one’s knowledge... medical statements cannot be dissociated from the statutorily defined person who has the right to make them, and to claim for them the power to overcome suffering and death. But we also know that this status in Western civilisation was profoundly modified at the end of the eighteenth century when the health of populations became one of the economic norms required by industrial societies.

‘We also know…’ We have to admit that Foucault hardly gives us the means to move from this hearsay knowledge to a rational knowledge of the process of modification. Always the same enigma: that of the ‘clutch’. But this text is exceptional, in that it allows us to clarify – in all its richness – the functioning of the category of ‘rule’ in Foucault’s work: it goes together with the notions of status, norms and power. Very precisely: status is defined by a non-discursive instance: we can say by a part of the state apparatus, it embodies and realizes a certain number of norms defined according to economic imperatives. This status, literally, gives the profession a body, and this body invests the discourse that is held within it – and therefore the individuals who hold it – with a power. We can see that this last power – which has no other existence than in the discursive practice of doctors – insofar as it is not foreign to the state apparatus, has some relationship, not specified by Foucault, with state power. Let us leave this analysis here, to encounter the same problem elsewhere.

Foucault displays embarrassment and vagueness in this analysis on several occasions: thus (p. 61) describing the formation of an object of knowledge as a ‘complex group of relations’, he proceeds to an unprincipled amalgam: ‘These relations are established between institutions, economic and social processes, behavioural patterns, systems of norms, techniques, types of classification, modes of characterization; and these relations are not present in the object’ (p. 45).

One could quote several other texts just as rhapsodic as this one (notably p. 72).

It is time to call things by their name and to see why, having made a mistake, Foucault had to come a cropper. If we gather the elements gathered along the way, here is the type of analysis we can propose. Starting from a critique of Althusser’s former and overly narrow notion of ideology, Foucault elaborates his own category of ‘knowledge’ and supports it with a poorly constructed concept of ‘practice’. Poorly constructed, since the need is felt to split it in order to make it fulfil its function, without being able to give a reason for this split. But, benefiting from the fact that his critique is correct, he reproduces, albeit out of place, the determinations of the scientific concept of ideology as it actually functions in historical materialism. Since he has, from the outset, deprived himself of this concept, when the essential difficulty of the ‘link’ between ideology and the relations of production arises, he is left speechless, condemned to designate the locus of a problem in a ‘mystified’ way.

1.) The concept of ideology as it functions in historical materialism – for Marx and his successors – is not in fact the pure reverse of science. Foucault is perfectly right; the question he poses of the ‘regime of materiality’ of ideology is a real (materialist) question of urgent theoretical necessity for dialectical materialism. We know that ideology has a consistency, a material existence – notably ‘institutional’ – and a real function in a social formation. Likewise that in Marx’s still descriptive scheme of the structure of a social formation, ideology (or ideologies) is included in the ‘superstructure’. The superstructure, determined ‘in the last instance’ by the economic infrastructure, is said to have a ‘feedback effect’ on the infrastructure. As such, ideology cannot disappear simply because of the appearance of science. We thus understand in what sense Michel Foucault is right to want to work ‘at another level’ than that of an epistemology of ‘rupture’:

‘Rupture is not for archaeology the prop of its analyses, the limit that it indicates from afar, without being able to determine it or give it its specificity; rupture is the name given to transformations that bear on the general rules of one or several discursive formations’ (pp. 176-7). To determine ideology as an ‘instance’ of any social formation is in fact to force oneself to think of ideology not only, in strictly Bachelardian style, as ‘a fabric of tenacious errors’, woven in the secret of the imagination, as the ‘shapeless magma’ of those ‘theoretical monsters’ that precede science – and often survive it with a pathological existence; it is to oblige oneself to think the constitution, the functioning and the function of this instance as a historically determined material instance in a complex social whole, itself historically determined. It is, it seems to me, the quite exemplary value of Foucault’s Archaeology that this was attempted.

[book-strip index="4" style="display"]2.) The fact remains that this attempt ends in failure: Foucault’s analyses ‘stumble’ on the blind distinction between discursive and non-discursive practices. In reality, if what we have just said is correct, there is no need to be surprised: it can be shown that by this single distinction Foucault is seeking to solve three distinct problems -- problems that can only be formulated in the concepts of historical materialism. Three problems whose effects Foucault encounters in the form of embarrassment, for lack of having been able to pose them.

Problem number 1: this concerns the relationship between an ‘ideological formation’ and what Foucault calls ‘social relations’, ‘economic fluctuations’, etc. In short, what we have, on several occasions, referred to as the ‘clutch’ problem. In other words: in a social formation, what kind of relationship does ideology have with the economic infrastructure? A naive question, one might say, to which a Marxist will easily answer with the classical scheme of infrastructure and superstructure. In truth, the answer, while easy and fundamentally correct, is probably not sufficient. It is still descriptive; even if it has the invaluable advantage of ‘showing’ what the materialist order of determination is, even if it has a proven polemical value against all the idealist conceptions of history in which it is ideas that lead the world; even if, for these decisive reasons, it must be resolutely defended as a theoretical achievement of Marxism, insofar as it makes it possible to draw a line of demarcation between the two ‘camps’ of philosophy, between our adversaries and ourselves, we must recognize none the less that it does not give us the means to think the mechanism that links ideology as a system of hierarchical relations producing a subjecting effect on ‘subjects’ with the mode of production (in the strict sense), i.e. the system constituted by the relations of production and the productive forces.[4] It is precisely such a mechanism that Foucault challenges us to conceive theoretically; with the notion of a ‘clutch’, he designates the place of an urgent theoretical problem: to move from descriptive theory to an actual theory of the relationship between ideology and infrastructure. We know that only historical materialism can solve this. Without being able to provide a solution here, we can at least add a clarification of the terms of the problem: if it is true, as the classical schema indicates, that it is the infrastructure which is decisive, we must ask ourselves: what is it about the mechanism regulating relations between these two systems, productive forces and relations of production, that produces the need for a system of ideological subjection? One day we will have to answer this question; Foucault’s merit is to have ‘rediscovered’ it – albeit in a displaced way – and shown us the urgency of it.

Problem number 2. This concerns the status of those ‘false sciences’ that are the object of Foucault’s earlier work. He insists: general grammar, natural history, etc., can certainly, by recurrence, be said to be ‘ideological’ in the eyes of constituted science; no doubt it can even be shown that there are close links between these ‘ideological’ disciplines and the system of ideological relations existing in a given society at a given moment in its history. The whole of the Archaeology tends to prove this. The fact remains that ‘general grammar’ or ‘natural history’ do not have the same status as religious, moral or political ideology in the way they function in the social formation under consideration. An indication of this difference is that these disciplines – whether we like it or not – call themselves ‘sciences’. In short, Foucault wants to avoid a ‘reduction’, which we would willingly call ‘ideological’, that is basically mechanistic. He proposes, in fact, a distinction between two ‘forms’ of ideology; while being careful not to see in this only a ‘formal’ distinction (some systematized, others not) but by considering, on the contrary, that there is a ‘difference of level’ between them. I propose to understand him as referring to a distinction that can be formulated in the concepts of historical materialism as a distinction between ‘practical ideologies’ and ‘theoretical ideologies’. Of practical ideologies, Althusser gave the following – provisional – definition:

We understand by ‘practical ideologies’ those complex formations of assemblages of notions/representations/images on the one hand, and assemblages of behaviours/conducts/attitudes/gestures on the other. The ensemble functions as practical norms that govern the attitude and the concrete position taken by men towards real objects and real problems of their social and individual existence, as well as their history.

How can we conceive the ‘articulation’ of these practical ideologies with ‘theoretical ideologies’? What is a ‘theoretical ideology’? Formulated here in material terms, these are the questions Foucault asks himself in other terms. It is here that the canonical notion of the archive takes on its full meaning and scope. In order to show this, we should examine line by line the chapter entitled ‘the historical a priori and the archive’ (pp. 126-34). Justifying the use of the first locution, Foucault writes: ‘Juxtaposed these two words produce a rather startling effect; what I mean by the term is an a priori that is not a condition of validity for judgements, but a condition of reality for statements.’ From this it follows that the archive – taken in a radically new sense – is: ‘first the law of what can be said, the system that governs the appearance of statements as singular events’ (p. 129). And more generally: ‘It is the general system of the formation and transformation of statements’ (p. 130).

But this general system, as we have seen, is not autonomous; the law of its operation is itself constrained by another type of ‘regularity’, that of non-discursive practices. We will say that the formation of the objects of theoretical ideologies is subject to the constraints of practical ideologies. More precisely, we will argue that practical ideologies assign their forms and limits to theoretical ideologies. By proposing to work at the level of the archive, Foucault thus invites us to think about the mechanism that regulates these effects; he poses the following problem: according to what specific process do practical ideologies intervene in the constitution and functioning of theoretical ideologies? Or again, how do practical ideologies ‘represent’ themselves in theoretical ideologies? Here, again, Foucault poses a real – and urgent – problem. The answer provided by Archaeology is still only a sketch to be reworked on the solid ground of historical materialism.

Problem number 3. This concerns the type of relationship that exists between a theoretical ideology and a science. Here Foucault makes an important contribution: he shows that the problem cannot be solved if we pose it in terms of objects. To compare the objects of a theoretical ideology to those of a science is to condemn oneself to the description of a rupture that explains nothing. By establishing the necessity of ‘passing’ through the category of ‘knowledge’ – as Foucault has elaborated this – he gives a correct position of the problem. This problem is not that of the relationship of a given science to the theoretical ideology that seems to ‘correspond’ to it, but that of a science to the system constituted by theoretical ideologies and practical ideologies, as it has been brought to light. Now, if, as we have just seen, the practical ideologies ‘re-present’ themselves in theoretical ideologies by assigning them their forms and limits, we will have to admit that a science can only appear in favour of a play in this process of limitation; which is why Foucault proposes to substitute for the term of rupture what I would see as a better term, that of the ‘irruption’ of a science. This irruption takes place in knowledge, that is to say in the material space where the system of practical and theoretical ideologies is played. It is, according to Foucault, by this means that we must think of the insertion of a science into a social formation; it is by this means that we avoid both idealism, for which science falls from the sky, and the mechanical-economistic, for which science is only a reflection of production.

It is time to show, by way of conclusion, how this type of analysis can work. Let’s take the example of the relationship between Marx and Ricardo. Foucault writes this striking text:

Concepts like those of surplus value or falling rate of profit, as found in Marx, may be described on the basis of the system of positivity that is already in operation in the work of Ricardo; but these concepts (which are new, but whose rules of formation are not) appear – in Marx himself – as belonging at the same time to a quite different discursive practice: they are formed in that discursive practice in accordance with specific laws, they occupy in it a different position, they do not figure in the same sequences; this new positivity is not a transformation of Ricardo’s analyses; it is not a new political economy; it is a discourse that occurred around the derivation of certain economic concepts, but which, in turn, defines the conditions in which the discourse of economists takes place, and may therefore be valid as a theory and a critique of political economy (p. 176).

The best commentary we can give on this analysis is to confront it with a passage from the Postface to the second German edition of Capital:

In so far as political economy is bourgeois, i.e. in so far as it views the capitalist order as the absolute and ultimate form of social production, instead of as a historically transient stage of development, it can only remain a science while the class struggle remains latent or manifests itself only in isolated and sporadic phenomena. Let us take England. Its classical political economy belongs to a period in which the class struggle was as yet undeveloped. Its last great representative, Ricardo, ultimately (and consciously) made the antagonism of class interests, of wages and profits, of profits and rent, the starting-point of his investigations, naively taking this antagonism for a social law of nature. But with this contribution the bourgeois science of economics had reached the limits beyond which it could not pass.[5]

Here we can see what makes Foucault’s text so exceptionally interesting: we understand how Ricardo’s and Marx’s objects belong to the same ‘discursive formation’, how the theoretical ideology that is classical political economy is determined in its constitution by a system of limits produced by the constraints of practical ideologies; we understand by this the insufficiency of the epistemological point of view of the rupture (or break). But we also see what is missing from Archaeology: a class point of view. It is because Marx places himself at the point of view of the proletariat that he inaugurates a ‘new discursive practice’. In other words: practical ideologies are traversed by class contradictions; the same applies to their effects in theoretical ideologies. Only a change in the system of contradictions that is thus constituted makes it possible to move from ideology to science. These reflections, which are suggested to us by Archaeology, however rudimentary they may be, go beyond Foucault’s enterprise. They overflow it by necessity and their absence accounts for the displaced character of all Foucauldian concepts. As a result, Archaeology itself remains a theoretical ideology. Now, according to what we have just said, it is ultimately to a class position that we must refer in order to understand it. We now see the meaning of Foucault’s choice between historical materialism and his own constructions: this theoretical choice is ultimately political. We have seen in detail the effects of this choice: it assigns to Archaeology ‘the limit that it cannot exceed’. If, on the other hand, the ‘archaeologist’ changes terrain, there is no doubt that he will discover many other riches. One last note: he will then have ceased to be an ‘archaeologist’.

Translated by David Fernbach

[book-strip index="5" style="display"][1] Originally published in La Pensée, no. 152, 1970.

[2] English quotes here are from The Archaeology of Knowledge, trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Pantheon, 1971). L’Archéologie du savoir was first published by Éditions Gallimard in 1969. – Trans.

[3] ‘Embrayage’, the coupling or clutch in a gear system. – Trans.

[4] Cf. on this subject Althusser’s article in La Pensée, no. 151, June 1970.

[5] Karl Marx, Capital Volume One, trans. Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin, 1976), p. 96.