A Palestinian Story

Ghada Karmi recounts the forced exile of her family from Jerusalem in 1948, and her visit to their family home 50 years later.

April 1948

A mighty crash that shook the house. Something – a bomb, a mortar, a weapons’ store? – exploded with a deafening bang. The little girl could feel it right inside her head. She put her hands to her ears and automatically got down onto the cold tiled floor of their liwan with the rest, as they had learned to do. Shootings, the bullets whistling around the windows and ricocheting against the walls of the empty houses opposite, followed immediately.

‘‘Hurry up! Hurry up!’’ The danger in the air was palpable. The taxi stood waiting outside, its doors open, to take them away to where she did not want to go. The little girl wanted to stay right here at home with Rex and Fatima, playing in the garden, jumping over the fence into the Muscovite’s house next door, seeing her friends return, even restarting school, now closed since Christmas. Doing all the familiar things, which had made up the fabric of her young life. Not this madness. Not this abandoning of everything she knew and loved.

‘‘Get into the car! Quickly!’’ A brief lull in the fighting. They must hurry, pack their two cases and the eight of them somehow into the taxi. The driver kept urging them to hurry. He was frightened and clearly anxious to get out of their perilous, bullet-ridden street. Rex could not come with them. He must stay behind. She held his furry body tightly against her and stroked his long soft ears. She wanted to say, ‘‘Please don’t worry. It’s only for a week. They said so. You’ll be fine and we’ll be back.’’

But she knew somehow that it wasn’t true. Despite her parents’ assurances, a dread internal voice told her so. ‘‘Ghada! Come on, come on, please!’’ Rex inside the iron garden gate, she outside. The house with its empty veranda shuttered and closed, secretive and already mysterious, as if they had never lived there and it had never been their home. The fruit trees in the garden stark against the early morning sky.

Every nerve and fibre of her being raged against her fate, the cruelty of leaving that she was powerless to avert. She put her palms up against the gate and Rex started barking and pushing at it, thinking she was coming in. Her mother dragged her away and pushed her into the back seat of the taxi onto Fatima’s lap. The rest got in and Muhammad banged the car doors shut.

She twisted round, kneeling, to look out of the back window. Another explosion. The taxi, which had seen better days, revved loudly and started to move off. But through the back window, a terrible sight which only she could see. Rex had somehow got out, was standing in the middle of the road. He was still and silent, staring after their retreating car, his tail stiff, his ears pointing forward.

With utter clarity, the little girl saw in that moment that he knew what she knew, that they would never meet again.

***

I found the house in June 1998, the year of Israel’s fiftieth anniversary. The Jewish State flamboyantly celebrating its success, not a mention of the human cost it had entailed. Another hot day, another companion, Rami Heilbron this time.

There it was. The one with the brick-red roofed veranda, our house without question. The spell was broken, the mystery at an end. An ordinary house, much smaller than the one in my imagination. An upper storey built on its roof which had never been there before. The iron gates and railings painted black. They used to be grey. No Rex to wag his tail behind them. On the wall a plaque that read Ben Porath. The steps going up, so huge in my memory, really quite small, and the veranda where they led but a modest rectangle. The windows on either side of the front door not half so tall as I remembered them. The whole place a fraction the size it had been in my child’s memory.

I went up to the gate. There was an old woman in a rocking chair on the veranda. Children’s toys lying around. The black and brown mosaic floor was exactly as I remembered it, though here and there the colours had faded. In a flash, I saw Fatima resting on the floor, her eyes closed. No resemblance to the woman now in the rocking chair, white-haired, European-looking. I pushed the gate open and went up the steps.

She looked up surprised. I smiled. He started to speak in Hebrew. She held up her hand.

‘‘I’m sorry,’’ she said, ‘‘I don’t understand. I’m American. Do you speak English?’’ We nodded. He said, ‘‘Sorry to bother you, but she used to live here many years ago. This used to be her house and she has never been here since. She just wants to look around a little. Do you mind?’’ She looked bewildered. ‘‘I must ask my daughter-in-law.’’ She went into the house through our front door which had not changed an iota. She came back with a younger woman, plump, in a dark wig, with a toddler clutching at her skirt. ‘‘It’s OK with me,’’ said the younger woman, also in an American accent. ‘‘But my little boy is sleeping inside.’’

‘‘I just want to go in the garden and maybe a little into the house,’’ I said. Both the women stared at me. I walked down the steps, turned right into the garden. Again, much smaller than I remembered. The lemon tree under my parents’ bedroom window, still there. But the vine had gone and so had the apricot trees. At the back, more trees, but everything overgrown, untended, unloved. Windows which opened onto rooms no longer ours. The clothes line where Fatima hung out the washing had gone. In the top right-hand corner, the shed where Rex slept reluctantly at night, also gone. Then down the other side of the house. A child, my earlier self, playing under the mulberry tree, now also gone. Against the wall and spoiling the symmetry, a staircase leading to the upper storey that someone had thoughtlessly added on. A large palm tree which had never been there before.

I came back to the foot of the steps and went up to the veranda. The old woman watched me. I pushed open the front door, my heart pounding. Inside, it was dark, the floor still retained the old tiling here and there. The liwan. My father in his chair in the top right-hand corner, reaching for a book from the shelves on the wall. The room was now distorted by a staircase going up to the upper floor. The woman in the wig motioned me to be quiet. Her son was sleeping there. I tiptoed towards the back, which should have opened onto the dining room, the kitchen, our bedrooms. But now unrecognisable. A large modern kitchen, a Filipino maid who looked round at me in surprise.

I wanted to stay longer, to go into the room kept for visitors where my mother had had her istiqbals, into my parents’ room, into the room where we had slept. They were no longer there, knocked down at some time to make a larger central space. But more than anything, I wanted to be alone so that the memories could seep back. So that the ghosts could return and let me touch what I had buried for so long. God knows when there would be another chance, when I would ever be allowed in here again. But the woman was uncomfortable. She had regretted letting me in and clearly wanted me to go. I steeled myself to speak.

‘‘Would you tell me what you know about this house? Is your name Ben Porath?’’

‘‘No. That’s the owner. We’re just renting here.’’

‘‘Do you know when he got the house?’’ She shook her head.

‘‘Well, would you let me have his telephone number so I could talk to him myself?’’

She looked alarmed. ‘‘I don’t know. I’ll have to phone my husband. He’s at work.’’

I waited while she went into the back of the house. She returned very quickly. ‘‘I’m sorry, but he says we don’t want anything to do with it. It’s nothing to do with us.’’ I hid my disappointment as well as I could and thanked her. She followed me outside. The old woman was back in her rocking chair. They waited for me to go down to the gate and then shut it behind me. I crossed over to the opposite pavement to get a better view. To the right, the Muscovite’s house, as it used to be. To the left, I saw that our old neighbours’ house, the Jouzehs’, was also still there, better preserved and its garden better kept than ours was now. But of course it wasn’t ours any more and had not been for fifty years. Our house was dead, like Fatima, like poor Rex, like us.

***

I lay on my bed in the hotel near the Old City where I was staying. My limbs were leaden, my mind a blank. Inside me was a numbing emptiness. Then suddenly a sound, familiar and evocative. It was the call to prayer, beamed forth from the Haram al-Sharif, spreading through the Old City, travelling over the houses, over the cars, the modern office blocks and passing on to the hills beyond:

Allahu akbar – God is great!

Allahu akbar – God is great!

I testify that there is no god but God and Muhammad is His Messenger . . .

As the sound hit my ears, I sat up, wide awake. Mesmerised, I went to the balcony windows and threw them wide open, the better to hear it. On it came, over the Wailing Wall, over the huddle of poor Arab housing, over Israel’s brash buildings, its luxury hotels, its noisy traffic. The unmistakable sound of another people and another presence, definable, enduring and continuous. Still there, not gone, not dead.

I closed my eyes in awe and relief. The story had not ended, after all – not for them, at least, the people who still lived there, though they were now herded into reservations a fraction of what had been Palestine. They would remain and multiply and one day return and maybe overtake. Their exile was material and temporary. But mine was a different exile, undefined by space or time, and from where I was, there would be no return.

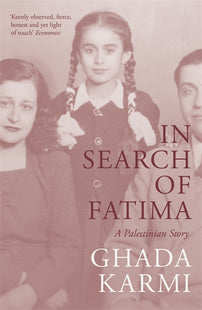

— An edited excerpt from In Search of Fatima: A Palestinian Story by Ghada Karmi.

See more of our publishing on Palestinian liberation here.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]