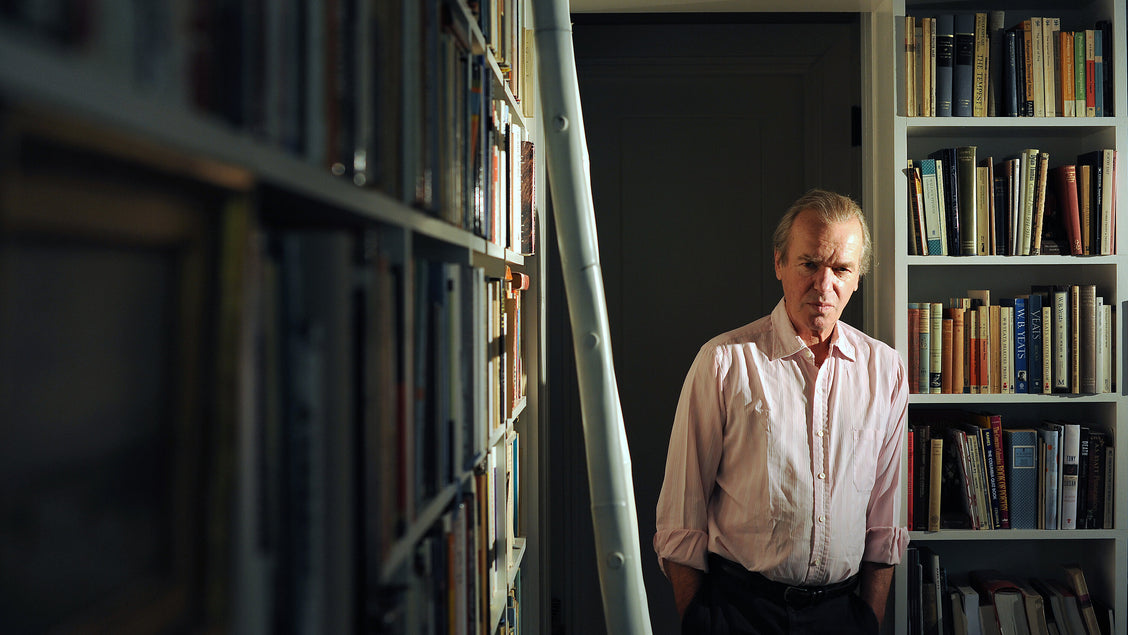

Remembering Martin Amis

Martin Amis, who died aged 73 earlier this year, has long been criticised from the left but for his political positions––first with Stalinism in Koba the Dread and then Islamic terrorism and his mishandled remarks about the Muslim community. But, argues critic Jared Marcel Pollen, it is for his style that he should be remembered more than his punditry.

In reading, as in writing, the pleasure principle is supreme. The authors you would most wish to save from a fire, or take with you to a desert island would be those that most consistently deliver exhilaration. These writers speak to you with an immediacy and intimacy that make you feel like their ideal reader, the person for whom the work is intended. And in turn, you defy anyone to love them as much as you do. Martin Amis, who died in May this year, said that this was precisely the experience he had when reading his literary idol, Saul Bellow. In a 2000 interview with Charlie Rose, he said of Bellow’s last novel, Ravelstein: “I couldn’t imagine anyone getting more out of this book than I was getting.” Many of Amis’s own readers, I wager, would say the same of him. They would all readily elect themselves his readers. And this critic is no different: for me, few authors offer more pleasure per verbum and seem capable of such largesse.

My own copies of Amis’s books are affectionately decorated––their margins adorned with exclamation points and incredulous scribbles, along with underlines of things that I at one point hoped to poach (he was the kind of writer you wanted to steal from). There was a time when they lay permanently open on my desk, inviting guidance, and whenever I felt my own powers foundering, his books were the ones I would invariably pick up to reexcite my verbal energy. When news of his death was announced, I like so many felt obliged to pen an encomium, but resisted the urge. Obituaries, after all, should at least attempt a measure of sobriety or sangfroid, and I felt unable to write about him in a way that didn’t risk being a panegyric.

For any maturing writer, he was the perfect instructor. He spoke eloquently and insightfully about the craft and had a level of dedication that now seems increasingly rare. Over the course of nearly fifty years, he published 27 books (15 novels, 4 collections of short fiction and 8 works of nonfiction, including three essay collections)––averaging around a book every two years. It was a work ethic he no doubt inherited from his father, Kingsley Amis, who published over 35 books in his lifetime. Together, the oeuvres of father and son occupy several shelves; stacked on top of one another, they rival the height of a refrigerator.

Also inherited, it seems, was his commitment to language. In his preface to Kingsley’s excellent and entertaining book on usage, The King’s English (1997), Amis writes how his father admonished him early on in his career for using “enormity” to mean “something very big in size” rather than in the proper sense––“something very bad.” Ditto “infamous,” which has drifted into being a synonym for notorious and away from its original application to describe something morally reprehensible. “With infamous,” he adds, “we see linguistic incuriosity in its most damaging form.” He then reminds us that “dilapidated” should only be used when describing a building (and not, for example, an old car or a dead tree), since the Latin root of the word lapis means “stone.” Amis himself never wrote a book on craft or usage, though he did do something of the sort with his last novel, Inside Story (2020), a biography interpolated with writing advice––perhaps inspired by Norman Mailer’s The Spooky Art (2003)––in which a number of the above prescriptions appear.

Amis was morally devoted to matters of style. In his work we see that aesthetics are a kind of high-intuition, operating at an ethical register: “Style is morality. Style judges.” A true style, therefore, is only true if it remains “faithful to your perceptions.” Thus, Amis’s famous abhorrence of cliché. Like all second-hand language and ready-made locutions, clichés are mental as well as moral offenses. They are herd/heard words that stupefy and disable one from thinking for oneself. As his friend Christopher Hitchens once wrote of him, he intuited “the strong connection between linguistic and political atrocity” and that what distinguished him from his contemporaries was his “synthesis of astonishing wit and moral assiduity.”

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]

Much admired but never decorated by the literary establishment, the only prize Amis ever won was the Somerset Maugham Award for his first novel, The Rachel Papers (1973). And unlike his friends Salman Rushdie and Ian McEwan, he never wrote a novel––like Midnight’s Children or Atonement––that cracked a broader audience (even though Money (1984) has endured as a seminal work of late 20th century literature). The early novels, Dead Babies (1975), Success (1978), Other People (1981), earned him journalistic epithets like the “enfant terrible” or “bad boy” of British lit, tags that followed him around for the rest of his career, even into his 70s.

These early works were, by Amis’s own admission, “well behaved.” It was with Money however, that the fetters were finally removed and the prose kicked into high-gear, with a deftness and energy befitting the speed of the late century. In it, we see the full force of Amis’s high-decibel sentences, as in this superb passage from early on in the novel:

Fielding, tanned, tuned, a king’s ransom of orthodonture having passed through his mouth, reared on steaks and on milk sweetened with iron and zinc, twenty-five, leaning into his strokes and imparting topspin with a roll of the wrist. Me, I lolloped and leapt for my life at the other end, 200 pounds of yob genes, booze, snout and fast food, ten years older, charred and choked on heavy fuel, with no more to offer than my block drive and backhand chip. I looked up at the glass window above Fielding’s head. The middle-management of Manhattan stared on, their faces as thin as credit cards.

Muscular, ebullient, swaggering with cool euphony and lyric wit––it is, like so many of Amis’s sentences, instantly recognizable. (A critic once wrote somewhat disparagingly of him that his sentences should be accompanied by a registered trademark.) Amis said that his father often teased him about the refinement of his prose. Kingsley, who wrote poetry, regarded fiction as a more expeditious form and thought that his son’s novels were too preoccupied with achieving a poetic texture––advice that was also given, funnily enough, to Bellow (Amis’s other literary father) by one of his elders, W.H. Auden.

[book-strip index="2" style="buy"]

Money marked the beginning of what is arguably the golden age, which would span nearly two decades, during which the greatest works––London Fields (1989), Time’s Arrow (1991), The Information (1995), and his memoir, Experience (2000)––were composed. My favourite is Time’s Arrow, perhaps Amis’s most uncharacteristic novel and his most ambitious conceptually. A story about the life of a Holocaust doctor told backwards, the novel is narrated by a voice that is estranged from the body that ferries it around, a consciousness that is observantly and ironically detached from its host. The narrative doesn’t just reverse the chronology of events, but the logic of causality: people sit down on the toilet and their feces go back up into them, relationships begin with death and end in marriage, dates commence with sex and finish at dinner.

These reversals often produce stunningly defamiliarized pictures of the world as well as disarming redirections in good and evil deeds. Hospitals, we see, are not houses of healing, but atrocity centers, where patients arrive well and leave ill. The Second World War kicks off with the de-detonation of the atomic bomb, with the genie being bottled. And it is here that the reversal of time engenders a reversal in morality: when we come to Auschwitz, we find that European Jewry is restored, as six million are loaded onto trains and sent out of the camps, back to their homes and their families. Thus, the great calamity of the century transforms into a eucatastrophe.

The post-millennial novels, Yellow Dog (2003), House of Meetings (2006), The Pregnant Widow (2010) and Lionel Asbo (2012), though they contain flashes of brilliance, are far less consistent. Even more troublesome were the forays into history and punditry, first with Stalinism in Koba the Dread (2002) and then Islamic terrorism in The Second Plane (2008). The former received some of the worst reviews of Amis’s career. The book zealously (and sometimes mockingly) takes upon itself the responsibility of reasserting the horrors of Stalinism, a subject that has been well treated by others far more qualified. However sound in its moral indignation, the book rigs itself up as a kind of cudgel against the left, which Amis argues, has failed to fully acknowledge the crimes of the Soviet Union. The book drew an especially sharp and poignant critique from Hitchens, who pointed out that Amis, besides “exhibiting a tendency to flail,” had conducted himself like someone who arrives late to history and then proceeds to lecture everyone about it. More still, Amis fell for the old moral equivalence between Nazism and Communism, utterly ignoring the legacy of the left opposition against Stalin.

When it came to politics, Amis was a self-professed “dilettante.” He was never as left as Hitchens and James Fenton, originally his colleagues at The New Statesman in the 1970s (in Experience, he recounts how he would tease both of them for spending their Saturday mornings handing out Trotskyist pamphlets), though he opposed the Vietnam War and wrote incisively about the absurdity of nuclear weapons in Einstein’s Monsters. In time, both Hitchens and Amis would find themselves on the defensive for their politics post-9/11. Whereas Hitchens became one of the leading advocates of the Iraq War and befriended its Straussian architects, Amis confined himself to writing about what he called “Islamism” and “horrorism.”

He came under fire for a mishandled remark in a 2006 interview, in which he said that “The Muslim community will have to suffer until it gets its house in order.” This prompted an attack from Terry Eagleton, who likened him to a bigoted “thug” and described Amis the elder as “a racist, anti-Semitic boor.” Eagleton seemed strangely deranged by Amis as a cultural figure tout court and later widened his ire to include the whole London literary “clique” (Hitchens, Fenton, McEwan, Rushdie) for being insufficiently leftist, or else reactionaries and defenders of a “complacent” liberalism. (Amis dismissed Eagleton as trafficking in gutter discourse. The whole episode showed, if nothing else, that political and journalistic clichés often go hand-in-hand.) Amis would continue to write about jihadism and its cult of righteous violence in the years that followed, with mixed results, and many of these pieces, including a very Conradian story, “The Last Days of Muhammad Attah” would make their way into The Second Plane.

Amis was an especially gifted critic, and his discursive writings are often as perceptive as his fictions (many, in fact, find his criticism to be superior). There have been many excellent novelists who proved to be good critics (John Updike) and excellent critics who were fair novelists (George Orwell), but to be great at both is exceedingly rare. This is because criticism is composed using the rational faculties; it is written with the left-hand (that is, the right brain). Fiction, by contrast, is essentially irrational, right-handed (left-brained). Most writers have one dominant hand, but Amis was remarkably ambidextrous. His essays and reviews are full of the language of literature itself (lyricism, imagery, metaphor) and he did his best work when animated by the writers he most loved––even if it was about what he loved least, as in this passage on Nabokov’s Ada or Ardour (1969):

In common with Finnegans Wake, Ada probably does ‘work out’ and ‘measure up’—the multilingual decoder, given enough time and nothing better to do, might eventually disentangle its toiling systems and symmetries, its lonely and comfortless labyrinths, and its glutinous nostalgies. What both novels signally lack, though, is any hint of narrative traction: they slip and they slide; they just can’t hold the road. And then, too, with Ada, there is something altogether alien—a sense of monstrous entitlement, of unbridled, head-in-air seigneurism. Morally, this is the world for which the twisted Humbert thirsts, a world where ‘nothing matters’ and ‘everything is allowed.’

Here we see the decorum that informed Amis’s sense of the novelist’s responsibilities to their readers. Despite his devotion to style, he remained curiously averse to what he saw as terminal aesthetics and solipsistic indulgences. “Only about two-thirds of Ulysses works,” he once remarked. He also described Finnegans Wake as “the ultimate reader-hostile, reader-nuking immolation…” Elsewhere, he wrote of Ada, “It is a waterlogged corpse at the stage of maximal bloat.”

Above all, he was a champion of social realism (even the postmodern games in Money and London Fields are low-key) and maintained that the great formal experimentations of the 20th century––from surrealism to the nouveau roman––had suffered popular defeat. The novel, he argued, is a social form and so it must have social skills. Talent unsupported by generosity is ultimately ineffectual (late Joyce, perhaps, was big on genius but short on grace). A good novelist therefore should be a good host. This is the conceit of Inside Story, which begins with him welcoming us, the reader, into his home, sitting us down and making us comfortable, and it ends with him escorting us out.

Reading it felt like a goodbye in more ways than one. “Now I must get ready to go, I’m afraid. Come on, I’ll see you to the door,” he writes in the novel’s closing passage. He tells us that this will likely be his last book and bids us farewell: “…I’ll miss you too, your warmth, your encouragement… Goodbye, my reader.” Later in life, Amis had taken to saying that writers die twice: first the talent, then the body. Not a problem for Jane Austin, who died at 41, or Shakespeare at 52. Life expectancy, it seems, has surpassed the half-life of one’s own gifts, forcing writers to suffer the indignity of creative decline. Stopping is thus an act of self-respect. At age 73, Amis likely recognized that his best work was behind him. He understood that sooner or later you have to leave the party. And now he has, but not without leaving the rest of us with plenty to read.

Jared Marcel Pollen is the author of The Unified Field of Loneliness: Stories (2019) and the novel Venus&Document (2022). His work has appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Gawker, Jacobin, Tablet, Astra, The Yale Review, and Liberties. He currently lives in Prague. Twitter: @JaredMPollen