Freud's Missing Object: The 1905 Edition of Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality

Ulrike Kistner's new translation of the first, 1905 edition of Freud's Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality is out this week. To celebrate its publication, all books on our psychoanalysis bookshelf are 40% off until Sunday, January 29 at midnight UTC.

In the essay below, the book's foreword, Kistner and scholars Philippe Van Haute and Herman Westerink (who also contributed an introductory essay to the new edition) outline the theoretical implications of the non-Oedipal psychoanalysis Freud pursued in this first version of the Essays — revised away in subsequent editions — and explain the necessity of a new standalone volume.

Sigmund Freud published the first version of Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality in 1905, the same year in which he published Fragment of an Analysis of Hysteria (“Dora”) and Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. These three books, together with others written in that period, can only be properly understood through the intrinsic reference that binds them to one another. These three books illuminate each other and Freud’s thinking in that period.

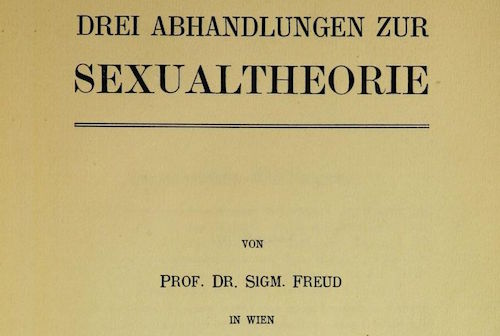

But something strange happened in the subsequent editions of Three Essays and their reception. Freud kept rewriting his Three Essays over the years. He republished them four times between 1905 and 1924, and each time he added large paragraphs in which he explained the theoretical insights that he had developed in the meantime. As a result, the 1924 edition of the text is twice as long as the original one, and it contains theoretical insights that bluntly contradict Freud’s original positions of 1905. It is this 1924 edition that was published in the final “officially approved” collection of Freud’s works. This at least partly explains why the first edition of Three Essays was never published in any language other than German. In this way, the first edition became like a missing object that every Freud scholar referred to as “1905d,” but that in fact was absent and unknown. At the same time, the officially approved version of 1924 was a decontextualized version no longer bound to Freud’s 1905 projects and thoughts.

This situation has undoubtedly had dramatic effects. Of course, it is well known that the text of Three Essays that we find in Gesammelte Werke and the Standard Edition is not the original version of 1905. James Strachey did a very good job in indicating — though with some omissions — the various changes and additions that were introduced between 1905 and 1924. But even the most experienced Freud readers have a very hard time distinguishing between passages that were introduced at different moments and that for that very reason belong to different theoretical contexts and have to be judged accordingly. It comes as no great surprise then that the psychoanalytic tradition — and this is only one example among many — consistently gives an oedipal interpretation of the Dora case, whereas there is not one reference to the Oedipus complex in the 1905 edition (There is one reference in a footnote to the “Oedipus fable” (p. 67), but one can hardly consider this an acknowledgment of a psychological Oedipus complex. This problem is further discussed in this translation’s introductory essay, “Hysteria, Sexuality, and the Deconstruction of Normativity—Rereading Freud’s 1905 Edition of Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality.”). Quite the contrary, according to this edition, the crucial problematic that lies at the basis of hysteria is not this famous complex, but bisexuality. Reading Dora against the background of the 1905 edition reveals a picture different from the one that emerged when the case history is read against the background of the 1924 edition.

But this is not all. The very idea of an Oedipus complex would have been a theoretical impossibility in 1905. Indeed, the complex implies that infantile sexuality is object-related. But in 1905, Freud consistently thematizes infantile sexuality as essentially autoerotic. Infantile sexuality is “without an object.” This also explains why Freud links oedipal themes in the first edition to (object-related) pubertal sexuality. This view is in direct contradiction with the historiographic tradition that until today claims that psychoanalysis starts at the very moment when Freud gave up the theory of seduction (his “neurotica”) in 1897, and reinterpreted the stories of his patients as the disguised expressions of oedipal fantasies. The history of Freudian thinking is in fact far more complicated than many would think, and the first edition of Three Essays is a crucial element in this history. Hence the importance of its translation.

The first edition of Three Essays is not only important for historical reasons. Psychoanalysis has been severely criticized in the past — and with good reason — for its heteronormative approach to sexuality. This approach can take many forms, but it is almost always linked to one of the many versions of the Oedipus complex. A critique of psychoanalytic heteronormativity, therefore, would have to entail a critique of the role accorded to the Oedipus complex. The first edition of Three Essays contains a theory of sexuality that in no way anticipates the later oedipal theories. Quite the contrary, the 1905 edition identifies infantile sexuality with nonfunctional pleasure, and discusses this relation without any reference to an object or to sexual difference. This approach allows for a critique of a binary conception of sexuality and, more generally, of sexual identity politics characterizing not only conservative theories, but also many feminist theories of sexuality.

In this first edition, Freud further conceptualizes a “patho-analysis” of (sexual) existence. In order to understand the (sexual) existence of the human being, one has to start from psychopathology. Psychopathology shows us in a magnified way the tendencies and problematics that we all have to deal with. In this way, psychiatry and psychopathology attain an anthropological significance. They inform us less about diseases or disorders than about the human being as such. This idea undermines the distinctions between “normal,” “abnormal,” and “pathological.”

All of this means, more concretely, that Freud’s first theories of sexuality resonate with later philosophers who, writing on related subjects, attempt to overcome heteronormative logics. One can think for instance of the writings of Foucault and Deleuze, and of queer theory. The first, “missing” edition of Three Essays would undoubtedly be an important document in a debate on the possibility of developing a psychoanalytic metapsychology that escapes the heteronormavity characterizing it until today. This is an urgent task if psychoanalysis is to become once again what it always claimed to be: a subversive theory of subjectivity.

But even as the first edition articulates a new revolutionary theory of sexuality, it also remains stuck, to some extent, in age-old prejudices about sex and sexuality. The structural presence of these prejudices makes the text ambiguous and inconsistent, while at the same time showing the problematic that Freud was trying to articulate. Precisely because this text illuminates, rather than simply neglects, the uncertainties and ambiguities with which many of us struggle, it might show us a possibility or possibilities for inventing new ways of thinking about sexuality that transcend the “heterosexual matrix” that in many respects conditions our lives.

We cannot turn to Three Essays for rethinking the foundations of psychoanalytic theory without freeing the text from the later additions that risk hiding its originality from our sight, and without also carefully looking at the passages that were deleted in later versions. The 1905 edition is only partially and indirectly available in English through Brill’s seldom-referenced translation of the second edition of 1910, Strachey’s translation of the edition of 1924 in the Standard Edition, and Shaun Whiteside’s more recent translation of that same edition. These translations undoubtedly have many merits, but they also have their limitations. The fact that the 1905 edition of Three Essays has never been translated before creates a welcome opportunity for a more literal translation that at the same does justice to the subtleties of Freud’s concepts. Only in this way can we measure the importance of this foundational text. Hence the necessity of a separate edition and a critical introduction that locates the first edition of Three Essays in its historical context and examines its differences from the later versions.

Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality is out now.

All books on our psychoanalysis bookshelf are 40% off until Sunday, January 29 at midnight UTC.