The Novel of Lenin: Chapter Seven

The seventh installment of our nine-part series: The Novel of Lenin by Joseph Andras: The Imperialist War, the Founding of the Third International

1914-1917: The Imperialist War, the Founding of the Third International

In France, the French Section of the Workers International (SFIO) votes on war credits. The German Social Democratic Party does the same. Lenin sees it as treason, pure and simple. A new project is in order: a Third International.

We are in 1915. The French Section of the Workers International (SFIO) has voted for war credits. “French socialism has been decapitated,” Trotsky writes. “The” reversal “seems complete,” Stéphanie Prezioso comments in 2017 in Contre la guerre 14-18 (Against the 14-18 War). The German Social Democratic Party votes for them as well – “Both Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin suffered nervous prostration, and were at one moment near to suicide,” writes John Peter Nettl in his biography Rosa Luxemburg. Lenin, like her, couldn’t get over it: “Treason, pure and simple.” Socialism cannot espouse the agenda of the bourgeoisie and of capitalism. No sacred union. No social chauvinism. Lenin declares the death of the Second International, then three million members strong, and celebrates the hypothesis of the military defeat of the Russian Empire. All that remains is to turn the imperialist war into a revolutionary civil war. Trotsky calls for the immediate end of hostilities. If the war were to continue, “all Europe would emerge from it utterly broken,” he writes in his memoirs.

Germany turns British waters into a “war zone.” Reims is bombarded, and a zeppelin traps Paris. In the east, the Armenian genocide begins. Lenin reads Hegel, Heraclitus, and Aristotle. He never loses sight of the necessity of analytical work. No revolution without revolutionary theory – a well-known Leninist axiom. And then he lambasts Kautsky in passing, the figurehead of German Marxism, partisan of the vote for the credits in question: nothing but a “prostitute.” But already, he is occupied with a new project: found a Third International. A manifesto must be written. Debates, delegations, sub-commissions, it almost comes to blows. Trotsky is charged with writing a synthesis text. Lenin judges it too timid but votes for it anyway. It is adopted. “Among the anti-war revolutionaries Lenin stood practically alone in his ‘extremism’, in his advocacy of ‘revolutionary defeatism,’” notes Tony Cliff.

Rosa Luxemburg is incarcerated in Germany during the month of February for her opposition to the war. Behind bars, she writes The Crisis in the German Social-Democracy under the name Junius, adopting Engel’s phrases – socialism or barbarism – to adjust it to contemporary events. But socialist formations, she sums up, have, by their vote, the massacre of soldiers on their conscience. “This madness will not stop, and this bloody nightmare of hell will not cease until the workers of Germany, of France, of Russia and of England will wake up out of their drunken sleep; will clasp each other's arm's in brotherhood and will down the bestial chorus of war agitators and the hoarse cry of capitalist hyenas with the mighty cry of labour.” Lenin settles in Zurich in February 1916 and Luxemburg is liberated. The battle begins in Verdun. Our Russian eats many eggs and camps in the libraries. In May, he puts the final touches on Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism – it will be published the following year. Italy declares war on Austia-Hungary and Turkey on Romania. French soldiers reclaim the fort at Douaumont, the Battle of the Somme comes to a close after 141 days of combat. More than 200,000 English dead. More than 65,000 French. Some 170,000 Germans.

Rosa Luxemburg’s pamphlet appears. Lenin reads it, unaware that she is its author. He “heartily greet[s] the author” for its “splendid Marxian work,” albeit guilty, in his eyes, of some errors. One imagines, he says, “the picture of a lone man who has no comrades in an illegal organisation accustomed to thinking out revolutionary slogans to their conclusion and systematically educating the masses in their spirit.” The masses, still. Still and always.

This text was originally published by L’Humanité in a special edition commemorating the centenary of Lenin’s death. Translated from the French by Patrick Lyons.

Chapter Six: 1907-1914: The Revolution is Slow to Arrive, Jaurès is Killed, The Great War Arrives

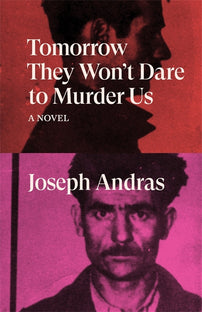

[book-strip index="1"]